Phil Ruthven reflects on the changing shape of consumer spending and its impact on business now and in the future.

The changing consumer marketplace

Consumers by and large have done very well for a very long time in Australia. The nation’s standard of living has almost trebled (2.6 times) over the past 50 years since our new age began after the industrial age in the mid-1960s. It has risen over six times in 100 years, and nearly 11 times since 1865 when the then industrial age began in earnest.

At the end of 2015, the average household was earning $150,000. This is a little misleading, as the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) included $14,500 in that income as “imputed dwelling ownership”, which is a non-cash estimate of the value to householders that own their own home. But even a net income of over $135,000 is impressive. Of course, it is not evenly distributed, as we know. The richest one-fifth of all households average $355,000, and the poorest one-fifth average $32,500. It is important to note, however, that the “poorest” include students, households temporarily out of work, as well as pensioners; and there is a substantive amount of government-provided non-cash benefits to many of these households that raises that average on an equalised basis.

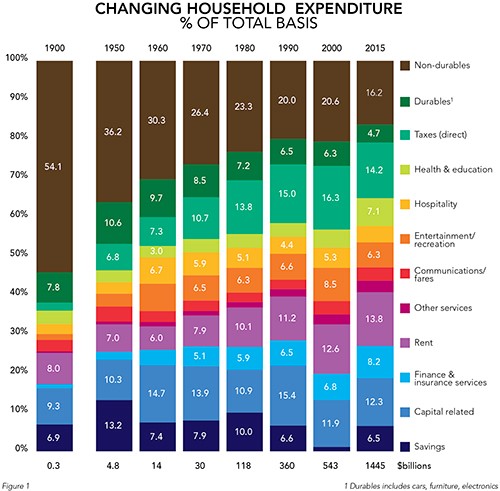

The way in which we have changed our spending patterns over a century is mind-boggling, as figure 1 reveals.

Tax allocation

At the turn of the 20th century, taxes were a negligible 2 per cent of incomes compared with 14 per cent today, plus GST and other embedded indirect taxes (including excises). If even 14 per cent seems low, it is important to remember that these direct taxes are for households, not an individual, and they are averages.

Some 60 per cent of all households pay only 13 per cent of all the income taxes; the rich and well-off (40 per cent of households) pay a whopping 87 per cent of all the taxes.

But equally revealing is the dramatic lowering of the proportion of incomes that went on shopping for goods, be they durable goods (cars, furniture and appliances) or non-durables (food, alcohol and cigarettes, clothing, fuel, pharmaceuticals and books).

The proportion has fallen almost two-thirds, from 62 per cent to 21 per cent of total incomes over the 115-year period. We are not consuming less of them; indeed we are consuming more per person than ever. It is just that prices have risen more slowly – if not fallen – compared with faster rising incomes.

We can thank the industrial revolution for those bargain prices; more recently the cheaper imports from Asia. We now spend more on entertainment than on food. We spend twice as much on hospitality than clothing ourselves. Indeed, almost three-quarters of our spending is on services (including our taxes that are returned as services in the forms of health, education and subsidised public transport).

Government has subsidised two-thirds of the nation’s spending on health for a century, via our taxes and that of companies. Clearly we want to live longer, healthier and pain-free lives. That comes at a cost, which we are prepared to pay, especially as other outlays on goods and services fall as a result of efficiencies and economies of scale by suppliers.

One of the dramatic lifestyle and spending pattern changes is the trend to outsource household functions and chores in the new age over the past five decades. This year, households will spend $410 billion on services such as meals, travel, holidays, financial advice, new health services, house cleaning, gardening and a host of other things that were DIY functions for households in the industrial age. That is an average of $42,700 per household, or $818 per week.

Consumption changes

Clearly the source of our goods and services is also changing. Online shopping has led to international sourcing through electronic department stores such as eBay, Amazon and other specialist online merchants. Services are imported too, notably in the form of international travel.

More of us holiday abroad than the numbers of inbound tourists; although this will reverse in the 2020s due to the boom in Asian (especially Chinese) travellers. China alone is expected to have well over 100 million outgoing tourists in the early 2020s.

Some habits change slowly, however. While shopping for goods is now poised to fall below a fifth of our incomes, we still do most of it in physical stores, be they shopping malls, clusters, arcades, strip-shopping areas or island sites. Yes, strip shopping is losing share, and shopping malls are providing service and entertainment outlets as well as shops to boost their growing significant share of the consumer dollar.

But online shopping is not yet 10 per cent of retail spending, even though it is double that level in other countries, including the UK. One could expect, however, that online shopping will be over a third by the middle of this century.

Competition for the consumer dollar is white-hot in some categories, and marketing has stepped up magnitudes in sophistication over recent decades; more so with the advent of the digital-disruption era that began in 2007 and will be magnified further when we get very-fast broadband to the 9.6 million households and 2.1 million businesses that make up the economy, which this year will have revenues in excess of $5 trillion. That is a slow and painful process at present, but hopefully will be given higher priority soon.

Main media advertising is unrecognisable compared with only a few decades ago. Print (newspapers and magazines) accounted for 50.5 per cent of the spending in the year 2000; but likely to be around 16 per cent in four years’ time in 2020. The internet, negligible in 2000, is now a third of all main media advertising and is expected to be a half in 2020 or shortly after.

Social media is ignored at one’s peril in business these days. The harnessing of consumer data into “big data”, combined with artificial intelligence software and analytics, is a powerful marketing cocktail.

All in all, the consumer marketplace is unrecognisable from that of yesteryear, still forever changing, and creating a “quick and the dead” arena for business. To the victor, the spoils.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content