The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) released its quarterly Monetary Policy Statement today Friday. The May statement says output is expected to contract significantly over the first half of 2020, mostly in the June quarter and that GDP is expected to fall by around 10 per cent. A baseline scenario assumes that most COVID-19 restrictions will lift by the end of the September quarter and that activity and employment will begin to recover in the second half of the year. We will examine this in more depth next week.

Earlier this week, The RBA left its main policy settings unchanged this week and markets expect a rock bottom cash rate for several years. The Treasurer put the economic costs of the current lockdown at almost $4 billion a week. ABS data show that over the six weeks to the week ending 18 April, employee jobs dropped by 7.5 per cent, while total wages paid slumped by 8.2 per cent. More than 70 per cent of businesses say they expect reduced cash flows to have an adverse impact on them over the next two months. Australian job ads have plummeted by more than 50 per cent. Consumer sentiment has been improving (albeit from very low levels). March saw both a record trade surplus and a collapse in tourism trade. National house prices kept rising last month.

This week’s readings look at the battle for the COVID-19 narrative, the pending litigation deluge, lessons from South Korea and the economics of the Second World War.

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

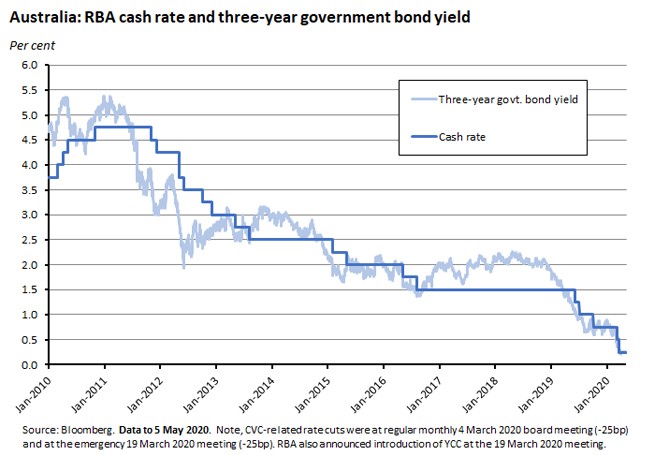

The RBA left its main policy settings unchanged at the 5 May meeting of the Reserve Bank Board, sticking with the existing targets for the cash rate and the yield on three-year Australian Government bonds of 25 basis points.

The accompany statement noted that financial markets across the global economy were now working more effectively than they were a month ago, although in the RBA’s view ‘conditions have not completely normalised.’ Credit markets have opened to more firms and long-term bond rates remain at historically low levels. That improvement has been paralleled here in Australia, with improved functioning of the government bond market.

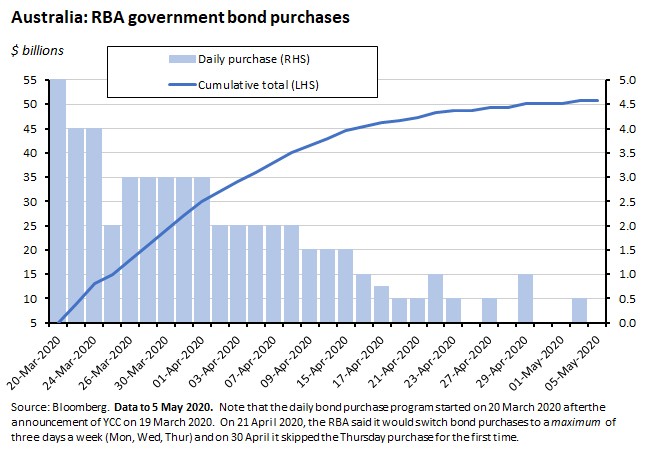

Together with the yield on three-year Australian Government Securities (AGS) sitting at the RBA’s target of ‘around 25 basis points’, that stabilisation in market conditions has allowed the central bank to scale back both the size and the frequency of its bond purchases, which at the time of writing stood at a little over $50 billion. But the statement also stressed that the RBA was ‘prepared to scale-up these purchases again and will do whatever is necessary to ensure bond markets remain functional and to achieve the yield target for 3-year AGS.’

This month’s meeting also saw the RBA announce that to ‘assist with the smooth functioning of Australian capital markets, the Reserve Bank has broadened the range of corporate debt securities that are eligible as collateral for domestic market operations to investment grade’.

The statement provided another preview of the RBA’s views on the economic outlook, which will be presented in detail in Friday’s Statement on Monetary Policy. At the global level, the Bank noted that ‘containment measures have reduced infection rates in a number of countries. If this continues, a recovery in the global economy will start later this year, supported by both the large fiscal packages and the significant easing in monetary policies’. In Australia, the RBA’s baseline scenario is still in line with the projections outlined in Governor Lowe’s 21 April speech: Output is expected to fall by around 10 per cent over the first half of 2020 and by around six per cent over the year as a whole, followed by a bounce-back of six per cent next year. The unemployment rate is expected to peak at around 10 per cent and to still be stuck above seven per cent at the end of next year. Finally, inflation is expected to be between one and 1.5 per cent in 2021 and to only gradually pick up from there.

The RBA is also considering alternative scenarios, noting that a ‘stronger economic recovery is possible if there is further substantial progress in containing the coronavirus in the near term and there is a faster return to normal economic activity. On the other hand, if the lifting of restrictions is delayed or the restrictions need to be reimposed or household and business confidence remains low, the outcomes would be even more challenging than those in the baseline scenario.’

Why it matters:

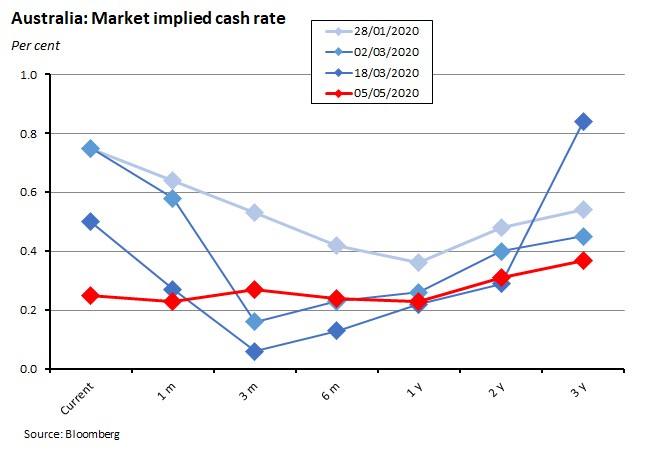

No change to key policy settings was expected this month. Indeed, markets are currently expecting little change to the cash rate for at least the next three years.

With the RBA predicting high unemployment and subdued inflation in its baseline forecast, the most likely scenario for now is that Yield Curve Control (YCC) and a cash rate stuck at the effective lower bound are going to be with us well into 2022.

One change that the RBA did announce this week was a broadening in the eligibility of corporate debt securities as collateral for its domestic market operations. It will now accept non-bank corporate securities with an investment grade rating.

(That means that for long-term corporate debt securities, the minimum eligibility requirement is now an average credit rating of BBB- whereas previously it had been an average rating of AAA. For short-term corporate debt, the minimum is now an average credit rating of A-3 instead of A-1.)

By accepting investment grade corporate debt as collateral in its market operations, the RBA is hoping to buttress the liquidity and therefore the attractiveness of corporate credit and thereby help lower spreads and ‘assist with the smooth functioning of Australian capital markets’. Prior to this announcement, spreads on non-financial corporate debt had remained elevated even while spreads on bank debt had retreated from their early April spikes.

What happened:

Australian Treasurer Josh Frydenberg gave a speech to the Australian Press Club this week. According to the Treasurer:

- Treasury expects GDP to fall by more than 10 per cent in the June quarter, equivalent to a loss of $50 billion.

- Net overseas migration is expected to decline by around a third.

- Unemployment is expected to reach ten per cent in the June quarter.

- For every week that current restrictions remain in place, Treasury estimates that there will be close to a $4 billion reduction in economic activity from a combination of reduced workforce participation, productivity and consumption.

- Earlier in the crisis, Treasury estimated that the macroeconomic impact from closing schools and childcare centres for three months could result in around one million adults withdrawing from the workplace to care for children at home, reducing GDP by around $34 billion;

- The government has made over 80 regulatory changes designed to provide greater flexibility for businesses and individuals to operate: and

- More than 725,000 businesses employing more than 4.7 million Australians have formally registered for JobKeeper.

Why it matters:

The Treasurer’s speech emphasised the new economic consensus – that the economy is facing a broad economic shock that will be much more intense than that experienced during either the GFC or the early 1990s recession, noting, for example, that in the latter case Australia’s unemployment rate increased by five percentage points but did so over three years. In the case of the CVC, the same increase will happen within three months.

With its emphasis on the cost to the economy of the current public health measures – that figure of a near-$4 billion weekly loss to the economy – the speech also reinforced the message in the Prime Minister’s press conference on the same day, that the government is focused on ‘getting Australia back to work,’ but doing so in a ‘COVID-safe economy.’

Frydenberg’s speech also canvassed the need to think about the path ahead for the economy, including ‘the changes that will be needed to further drive economic growth and employment’. There were few concrete details here, although the Treasurer did stress that the ‘proven path for paying back debt is not through higher taxes…but by growing the economy with productivity enhancing reforms’ and that the government will ‘look at old and new reform proposals with fresh eyes…our focus will be on practical solutions to the most significant challenges which will be front and centre in the post crisis world’. According to the speech, that will include reskilling and upskilling the workforce, new infrastructure projects, regulatory reform, and tax and industrial relations reform as a means of boosting competitiveness.

What happened:

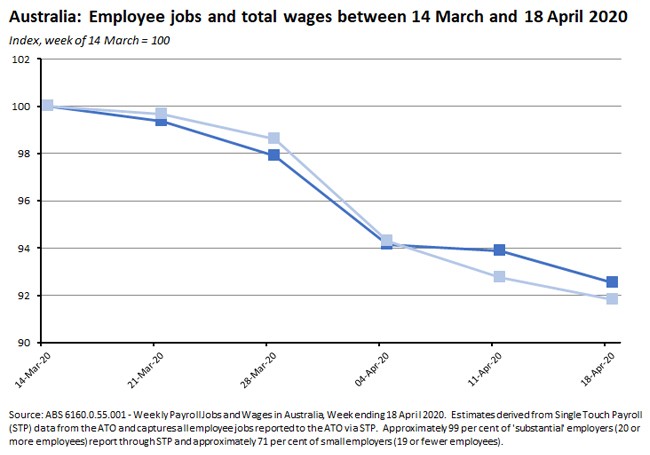

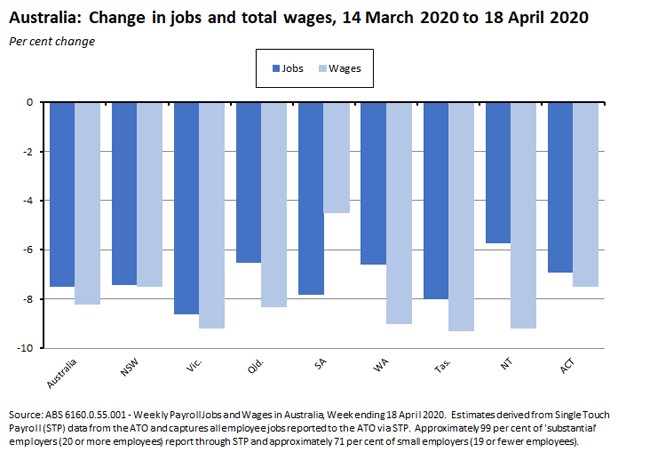

The ABS published the second in its new series Weekly Payroll Jobs and Wages in Australia, this time for the week ending 18 April 2020. The updated figures show that over the six weeks to the week ending 18 April, employee jobs decreased by 7.5 per cent while total wages paid decreased by 8.2 per cent. (The previous release, which covered the four weeks to the week ending 4 April had reported jobs down by six per cent and wages down by 6.7 per cent.)

By State and Territory, the largest changes in jobs were in Victoria (down 8.6 per cent) and Tasmania (down eight per cent) and the largest changes in the total wage bill were in Tasmania (down 9.3 per cent) and in Victoria and the Northern Territory (both falling by 9.2 per cent).

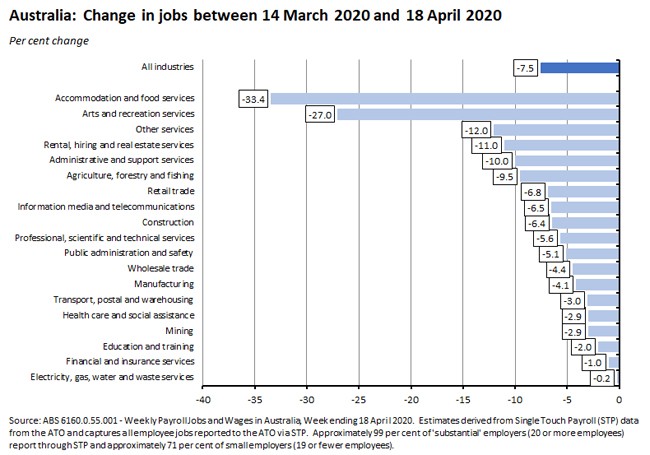

By sector, there were dramatic job losses in accommodation and food services (where more than one in three jobs has been lost) and in arts and recreation services (more than one in four jobs lost). There were also double-digit declines in other services; in rental, hiring and real estate services; and in administrative and support services.

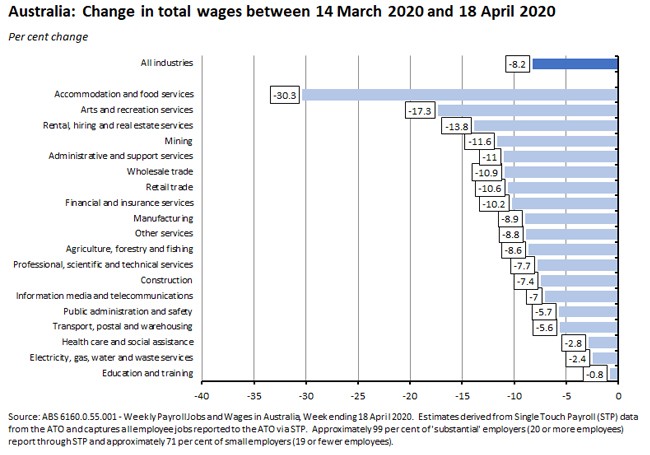

The decline in total wages was likewise largest in the accommodation and food services and in arts and recreation services, following by rental, hiring and real estate services.

The ABS also cuts the data by gender and by age. Jobs worked by females fell by 8.1 per cent over the 14 March – 18 April period, while those worked by males decreased by 6.2 per cent. Wage payments to females fell by 7 per cent and to males by 8.9 per cent.

By age group, jobs worked by people aged under 20 decreased by the most (a fall of 18.5 per cent), followed by those worked by people aged 70 and over (down 13.9 per cent). Wage payments to people aged over 70 decreased by 10.7 per cent while and payments to people aged 20-29 decreased by 10.3 per cent.

Why it matters:

The new ABS payroll data show that the big job losses reported a fortnight ago have continued into April. As a rough estimate, applying the 7.5 per cent fall in jobs reported here to the 13 million Australians employed according to the March labour force survey suggests a 975,000 rise in joblessness, which would take the unemployment rate to over 12 per cent. That’s almost certainly an overestimate since it doesn’t take into account double-counting (some workers will have held more than one job) and more importantly, any offsetting decline in the participation rate (as some workers who lose jobs will leave the labour force). But even making some downward adjustments to include those factors suggests that official predictions of an unemployment rate of around 10 per cent in the second quarter of this year look to be (un)comfortably right.

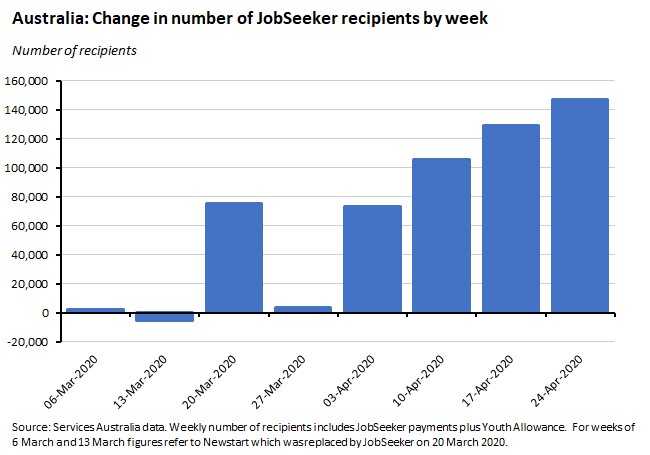

Additional evidence on the scale of job losses can be found in the surge in numbers registering for JobSeeker and related payments. According to data tabled by the Department of Social Services and presented to the Senate Select Committee on COVID-19 last week, the number of Australians receiving JobSeeker payments increased by 540,000 between the start of March and 24 April.

That took the total number of recipients (including those receiving Youth Allowance) to more than 1,346,000.

What happened:

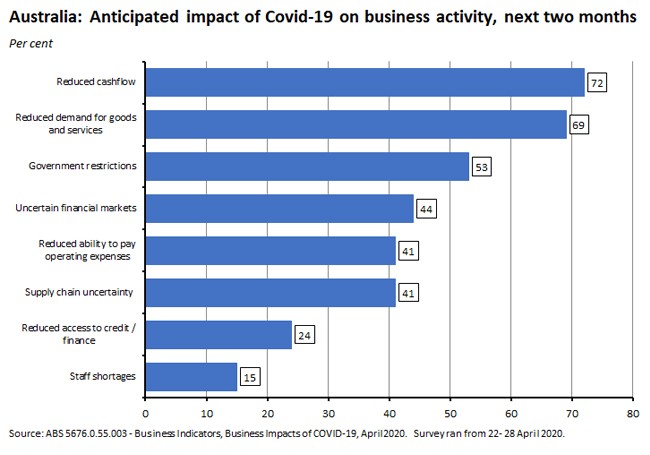

The ABS also released the results of its third survey on the Business impacts of COVID-19, conducted between 22 April and 28 April 2020. Key results included 72 per cent of businesses reporting that they expected reduced cashflow to have an adverse impact on them over the next two months (up from the 66 per cent who reported that COVID-19 was already having an adverse impact on turnover/cashflow in the ABS’ March survey) and 69 per cent saying that they expected that reduced demand for goods and services would have an adverse impact over the next two months (up from the 64 per who reported already having seen a fall in demand in the March survey).

Another key theme of April’s survey was business views on the JobKeeper program. Three in five businesses (61 per cent) reported having registered or intending to register for the JobKeeper Payment scheme, including 61 per cent of small, 60 per cent of medium and 45 per cent of large businesses. More than two in five businesses (44 per cent) reported that the announcement of the scheme had influenced their decision to continue to employ staff, including 45 per cent of small and medium businesses and 32 per cent of large businesses. By sector, businesses in accommodation and food services were the most likely to report that JobKeeper had influenced their employment decisions, followed by other services and construction.

Why it matters:

The survey shows that most businesses continue to anticipate significant adverse impacts from COVID-19 over the near term.

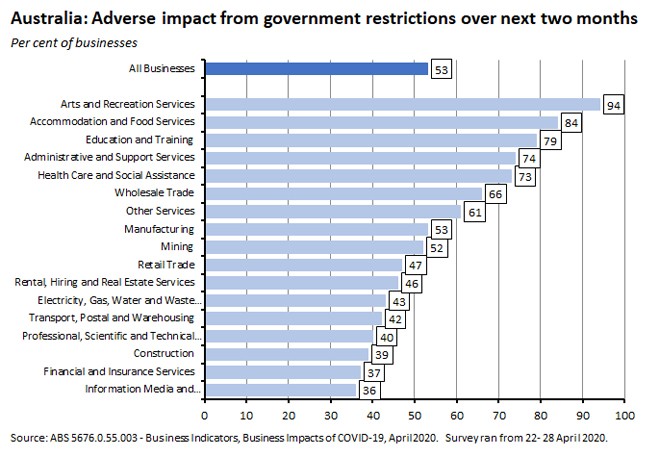

It is also possible to break those responses down by sector and by impact. So, for example, 94 per cent of businesses in the arts and recreational services sector are saying they expect to suffer an adverse impact from government restrictions over the next two months compared to 36 per cent in the Information, media and telecommunications sector.

If we map these results on to the share of each sector in GDP or gross value added (GVA), then the survey results imply that in sectors accounting for more than 40 per cent of GVA, at least half and in many cases many more firms are expecting to suffer an adverse impact from government restrictions over the next two months.

What happened:

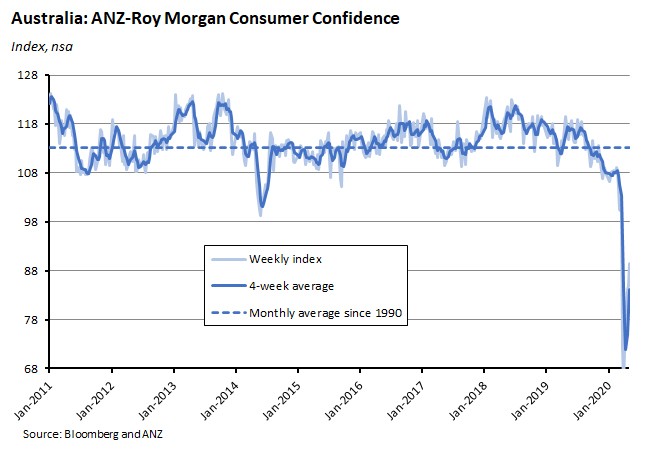

The ANZ-Roy Morgan weekly measure of consumer confidence increased by 4.5 points to 89.5.

All the subcomponents of the weekly index improved this month, except for Time to buy a major household item. So there were improved readings for Current financial conditions, Future financial conditions, Current economic conditions and Future economic conditions albeit from a very low base in most cases.

Why it matters:

This weekly measure of consumer confidence has now risen for five consecutive weeks after hitting a low of 65.3 at the end of March. It’s important to remember that still leaves consumer sentiment at GFC-like levels, which is far from any general return to optimism, but it does suggest that the good news on Australia’s success in driving down the number of new COVID-19 cases in recent weeks, and the consequent talk of a possible loosening of restrictions, has been having a positive impact on sentiment.

What happened:

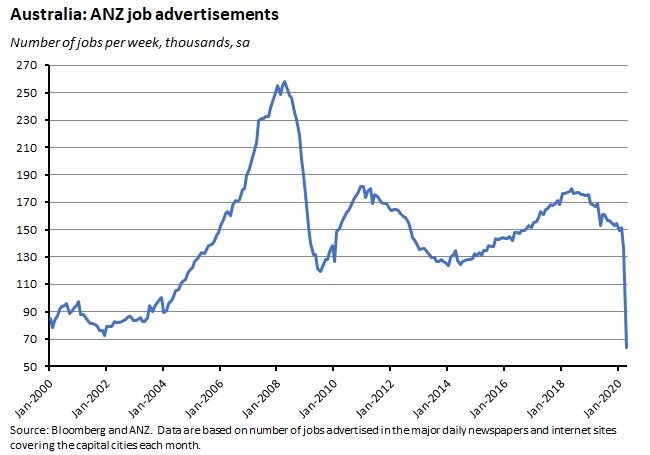

ANZ Australian Job Ads plummeted by 53 per cent (seasonally adjusted) in April, falling from more than 136,000 in March to less than 64,000 in April.

Why it matters:

The collapse in job ads in April was almost five times larger than the previous record monthly fall of 11.3 per cent that took place in January 2009, during the GFC. In line with the ABS weekly payroll data and the surge in JobSeeker recipients both discussed above, these numbers are more evidence of the huge negative shock that has hit the Australian labour market.

What happened:

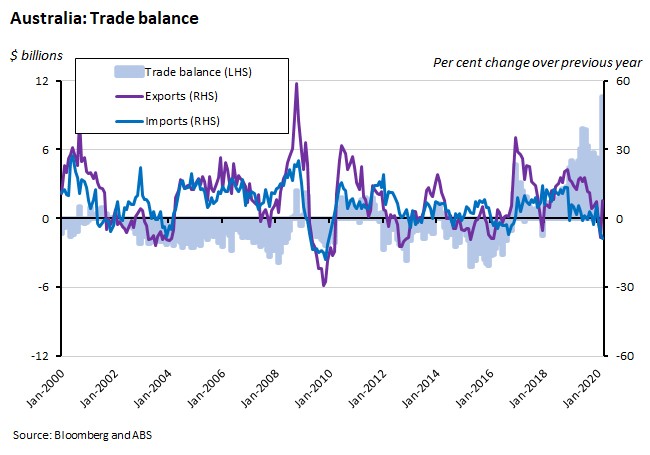

Australia reported a record $10.6 billion trade surplus in March (seasonally adjusted). The ABS said that exports of goods and services rose 15 per cent over the month while imports of goods and services fell four per cent.

The surge in exports was driven in large part by a 15 per cent increase in exports of non-rural goods which in turn reflected a 32 per cent jump in exports of ores and minerals, including a big rise in exports of iron ore. The latter were up 32 per cent over the month in March after having fallen by 14 per cent in February. That earlier drop was produced by the impact of cyclone Damien, which disrupted iron ore exports from Western Australia last month. There was also a 15 per cent increase in the value of exports of non-monetary gold. Together, that was all more than enough to offset a nine per cent fall in exports of services.

On the other side of the ledger, the fall in imports was powered by a three per cent drop in imports of capital goods and a 19 per cent collapse in imports of services.

Why it matters:

The rebound in the trade surplus in March to a new record level suggests there’s now a good chance Australia will run a fourth consecutive current account surplus in the first quarter of this year – something that hasn’t happened since the early 1970s. The sum of seasonally adjusted trade balances for the three months to March 2020 is a surplus of $19.5 billion, which represents an increase of $4.9 billion on the $14.6 billion surplus recorded in the three months to December 2019. The ABS points out that if seasonal factors used in compiling the quarterly balance of payments are applied to these numbers, then the preliminary March quarter 2020 trade surplus comes in at around $19.1 billion. That would be an increase of $5.5 billion over the December quarter 2019 surplus of $13.5 billion.

The strong performance by net trade could also offer some good news for Q1 GDP in circumstances where good results elsewhere look likely to be hard to come by.

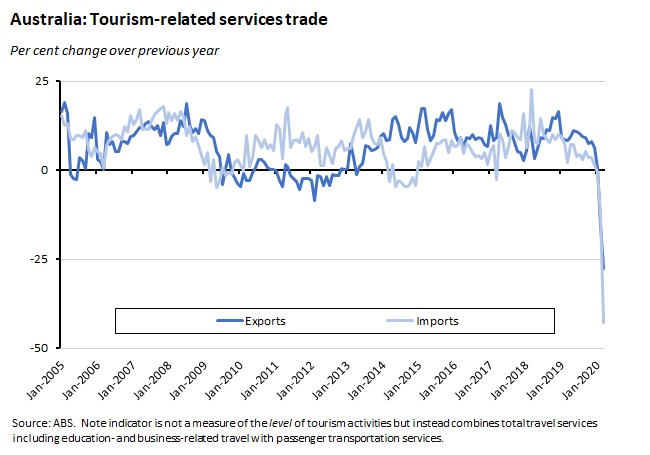

The March numbers also highlight the dramatic impact of the CVC on services trade as exports and imports of tourism-related services both dropped sharply, continuing and deepening their February slump.

What happened:

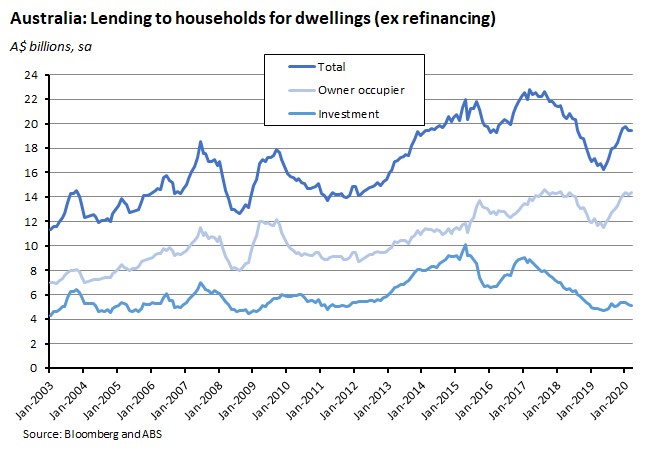

According to the ABS, lending to households for dwellings rose 0.2 per cent in March (seasonally adjusted), with new loan commitments for owner occupier housing rising 1.2 per cent and lending to investors falling by 2.5 per cent.

Why it matters:

Total new lending for housing was little changed in March despite COVID-19, although the ABS points out that March loan commitments largely reflected loan applications that had been submitted in February or the first half of March, and therefore largely captured the state of play before the major social distancing restrictions were introduced later that month. The ABS also commented that some lending institutions had reported a slowdown in new loan applications towards the end of the month.

Note also that lending to investors has now fallen for three consecutive months.

What happened:

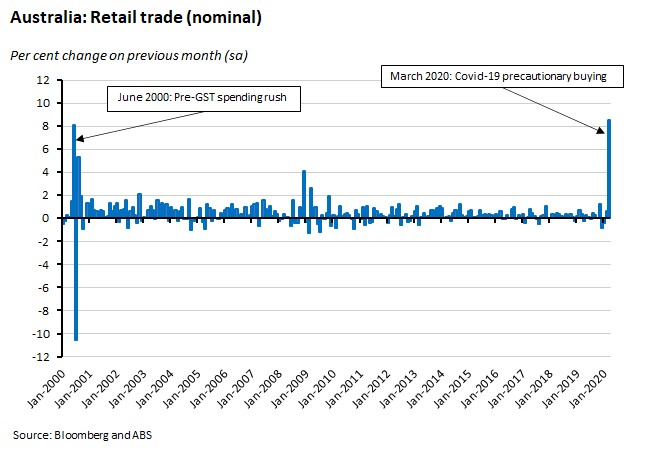

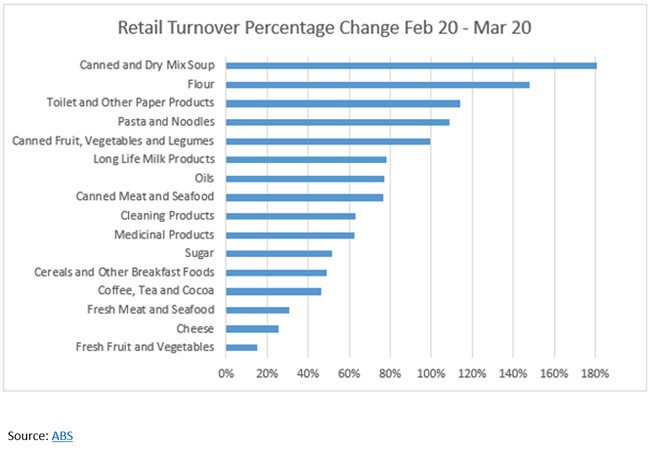

The ABS published the finalised results on retail turnover for March along with volume estimates for Q1:2020. The updated numbers show retail turnover rose 8.5 per cent in March (seasonally adjusted) to be up more than 10 per cent over the year.

The ABS also reported volume results for the quarter as a whole but in this case the big increase in monthly sales in March did not translate into particularly strong growth in volumes. Instead, volumes rose just 0.7 per cent over the quarter (seasonally adjusted) and were up 1.1 per cent over the year. That apparent discrepancy is because a lot of the action in March was reflected in a sharp rise in prices, rather than volumes, with higher prices acting to dampen some volume growth.

Quarterly rises in volumes were led by food retailing (up 6.4 per cent), other retailing (up 3.9 per cent), and household goods retailing (up 2.2 per cent). Those increases were partially offset by falls in cafes, restaurants and takeaway food services (down 8.4 per cent), clothing, footwear and personal accessory retailing (down 12.1 per cent), and department stores (down 5.2 per cent).

The ABS said that online retail turnover contributed 7.1 per cent to total retail turnover (original terms) in March, up from 6.6 per cent in February and 5.7 per cent in March 2019.

Why it matters:

The final nominal numbers for the month of March were in line with the preliminary estimate of an 8.2 per cent surge in monthly sales that the ABS had reported on 22 April, with a big spike driven by precautionary buying in response to COVID-19 that has delivered the largest monthly jump in sales on record. The ABS pointed to ‘unprecedented demand in food retailing, household goods, and other retailing’ alongside falling sales in cafes, restaurants and takeaway food services, and weak discretionary spending in clothing footwear and personal accessory retailing, and department stores. As a result, March saw both the strongest rise in food retailing, and the strongest fall in cafes, restaurants and takeaway food services, in the history of the series.

Famously, toilet paper and hand sanitisers were an important part of the retail story, although supermarket scanner data shows the biggest percentage chances were for canned and dry mix soup and for flour.

Retail sales account for about a third of household spending, so the first quarter numbers should make a positive contribution to consumption growth in the GDP results for Q1 (due on 3 June). However, the sharp drop in spending on services seems likely to have pushed the overall change in consumption into negative territory for the first quarter of this year.

What happened:

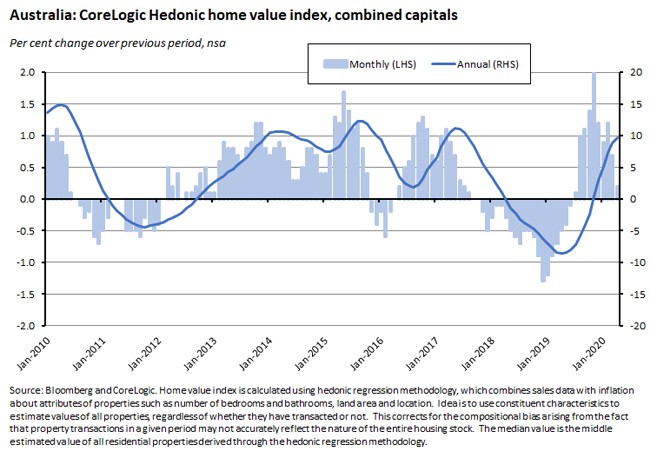

On 1 May, CoreLogic reported that Australian dwelling values across the combined capitals grew 0.2 per cent in monthly terms in April and were up 9.7 per cent over the year, while the national index rose 0.3 per cent over the month and increased 8.3 per cent over April 2019.

By capital city, only Melbourne (down 0.3 per cent) and Hobart (down 0.1 per cent) experienced monthly falls in April, although dwelling values in Canberra were flat.

Why it matters:

Home values continue to show resilience in the face of COVID-19. That said, the monthly pace of increase has fallen sharply in recent months, with the rate of growth of the combined capitals index falling from 1.2 per cent in February to 0.7 per cent in March and to just 0.2 per cent in April. But given the dislocation evident in the labour market and the big falls in consumer sentiment, the relative stability in housing values to date is notable. Very low interest rates and lender forbearance are both presumably playing a role here.

Instead, the bulk of housing market adjustment to date seems to be taking place in the form of a sharp decline in transactions. CoreLogic reported that its estimate of ‘settled sales’ fell by around 40 per cent in April as listings dried up and buyers pulled back. Likewise, it said that the number of new listings being added to the market was 35 per cent lower in April 2020 than in April 2019 and 45 per cent below the five-year average. So rather than households suffering large drops in the value of their home, the main pressure to date is being felt by those reliant on housing market activity: real estate businesses, banking and finance, removal services and so on. As we’ve noted before, a sharp fall in transactions will also put a big dent in state revenues in the form of reduced receipts from stamp duty – perhaps one factor behind the recent willingness of Victoria and NSW to consider the case for tax reform.

What happened:

Last Friday, the ABS published the results of its second survey of the Household Impacts of COVID-19, this one conducted over the period 14-17 Apr 2020. A major theme of this latest survey was the state of household finances and key findings included:

- Nearly a third of Australians (31 per cent) aged 18 years and over reported that their household finances had worsened over the period mid-March to mid-April due to COVID-19, while just over half (55 per cent) reported that their household finances remained unchanged.

- One in six Australians (17 per cent) reported that their household took one or more financial actions to support basic living expenses during the period mid-March to mid-April, with the most common options drawing on accumulated savings or term deposits (10 per cent) and reducing home loan payments (three per cent).

- Approximately one in four Australians aged 18 years and over (28 per cent) said they received the first one-off $750 economic support payment from the Commonwealth Government over the time period mid-March to mid-April.

- Of those who had received the payment: 53 per cent said it was mainly added to savings or not yet used; and 17 per cent said they mainly used it to pay household bills.

- For Australians aged 18 years and over, 12 per cent said they had experienced a change in their job situation since the end of March. Of these: 51 per cent said they had a job but were working less hours by mid-April; and 49 per cent said they had some other type of job change, such as working from home, had a job working no paid hours or they had lost their job.

The survey also collected information about Australians’ emotional and mental well-being, which was then compared with earlier results from the ABS’ 2017-18 National Health Survey (NHS). The results showed that, compared to the NHS, almost twice as many adults reported experiencing feelings associated with anxiety, such as nervousness or restlessness, at least some of the time.

Why it matters:

The survey results confirm that, as would be expected, the CVC is taking both a financial and an emotional toll on Australians.

The survey also reported a decline in household financial resilience. For example, while most Australians (81 per cent) said their household could raise $2,000 for something important within a week, this was lower than the 84 per cent share reported in 2014. The survey found that 12 per cent reported that their household could raise $500 but not $2,000 for something important within a week, and five per cent reported that their household could not raise $500.

Finally, there were also some interesting details on the differing age profile of the impact of the CVC. For example, the survey results suggest that Australians aged 65 years and over were less likely than persons aged 18 to 64 to have reported that their household finances had worsened (20 per cent compared with 35 per cent), were more likely to have received the first one-off $750 economic support payment than those aged 18 to 64 (60 per cent compared with 19 per cent), and more likely to have added that payment to savings or not yet used it than those aged 18 to 64 (71 per cent compared with 37 per cent).

What I’ve been reading:

The RBA’s May Chart Pack is now available.

Alan Mitchell on economic governance in a crisis.

Martin Wolf in the AFR looks at radical options to escape the debt trap.

Bowles and Carlin seek to prepare us for the coming battle for the COVID-19 narrative.

The Economist examines the 90 per cent economy.

An FT Big Read on the coming deluge of pandemic litigation.

Douglas Irwin discusses globalisation, slowbalisation and the coronavirus.

Arvind Subramanian worries that the CVC threatens to leave the world ‘even more rudderless, unstable and conflict prone.’

An Atlantic piece on the lessons from South Korea.

Why COVID-19 is inflicting more damage than the Spanish Flu.

Yuval Noah Harari asks will COVID-19 change our attitude to death.

A new e-book on the economics of the Second World War (this is on the ‘I’d like to read it if I get a chance’ pile: would be great to have some deep non-COVID-19 reading…)

Tyler Cowen in conversation with Adam Tooze.

A Grattan webinar on planning for recovery.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content