A weekly measure of consumer confidence has now improved for seven weeks in a row. Even so, retail turnover collapsed in April. Payroll data continue to paint a bleak picture of the overall state of the labour market, although there are some signs that the rate of deterioration may have eased. Both services and manufacturing continued to contract this month. The RBA’s efforts at yield curve control and bond market stabilisation have been successful enough that the central bank has been able to pause its bond purchases. Despite a run of bad economic news, global stock markets have been surprisingly resilient.

This week’s readings include the complications facing Australia’s pursuit of economic sovereignty, the potential of travel bubbles, the expansion of state power during the current pandemic, and a review of some of the cross-country health and privacy issues raised by deploying technology to combat COVID-19.

AICD is polling members on the impact of COVID-19. If you haven’t already responded and you can spare the time, it would be great to get your views. You should be able to access the survey here.

Finally, another reminder that in an upcoming webinar I’ll be looking at how the Coronavirus Crisis (CVC) is reshaping the international economic landscape. Interested readers can register here.

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

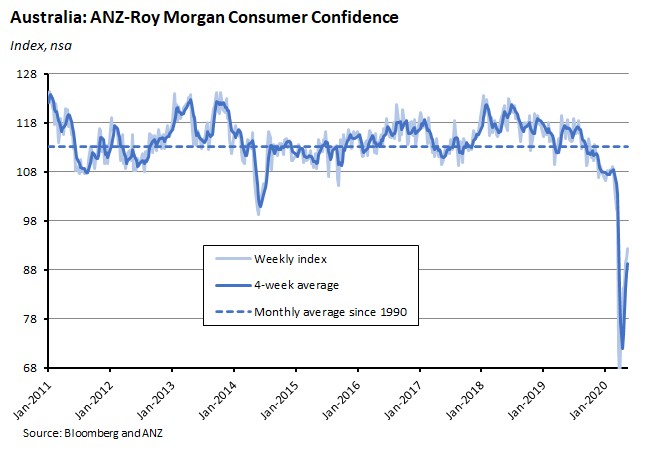

The weekly ANZ-Roy Morgan consumer confidence index rose by 2.2 per cent this week.

Why it matters:

This was the seventh consecutive weekly increase in the sentiment index, suggesting that the combination of substantial policy support plus a run of good news on the public health front and the prospect of more ‘opening’ of the economy together continue to drive some recovery in household confidence. Even so, the index is still down at about 20 per cent below its long-term average.

What happened:

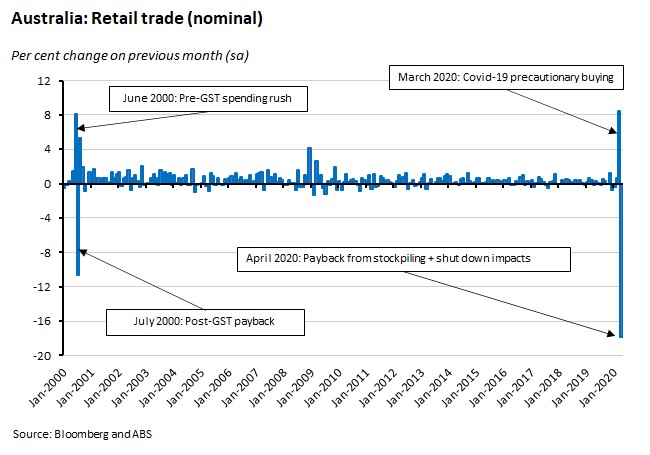

The ABS preliminary estimate of retail trade for April showed turnover plunging by 17.9 per cent over the month to be down by 9.4 per cent relative to April 2019.

According to the ABS, the collapse in turnover was driven by the food retailing industry, which fell 17.1 per cent in April, payback for the massive 24.1 per cent rise in March 2020 as households embarked on huge bout of stockpiling in response to COVID-19 (and despite April’s fall, sales in food retailing remained five per cent above the level of the same month last year).

April’s preliminary data also showed substantial declines in turnover for Cafes, restaurants and takeaway food services and for Clothing, footwear and personal accessories retailing. Turnover in both sectors last month was around half the level of April 2019.

The ABS also said that April was a strong month for online retailing, with ten per cent of total retail turnover purchased online, up from 5.7 per cent in April 2019.

Why it matters:

Last month the ABS reported March had delivered the largest monthly rise in retail turnover on record and now April has delivered the largest monthly fall. A substantial adjustment following last month’s surge in precautionary spending was always on the cards, but the negative effect of this drop has been reinforced by a further decline in spending on those sectors heavily affected by social distancing measures. Consumer confidence may now be showing signs of recovery (see above), but the blow to consumer spending was severe last month.

What happened:

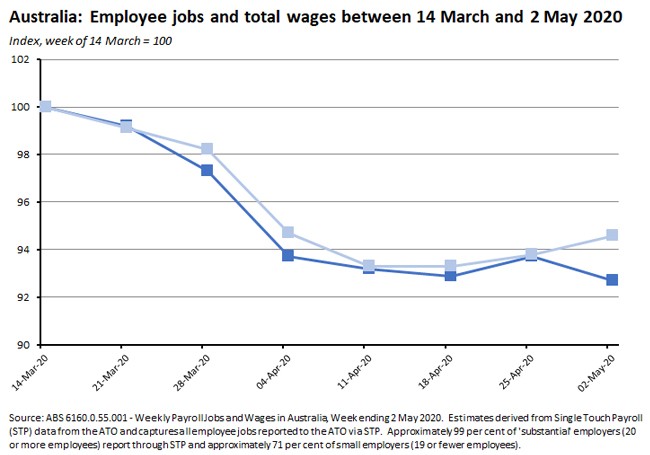

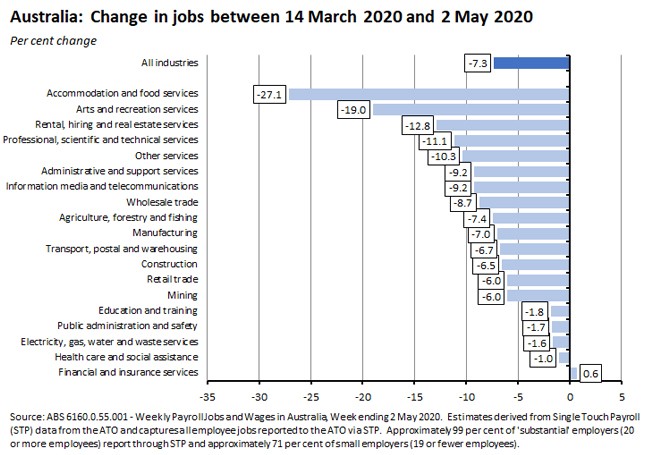

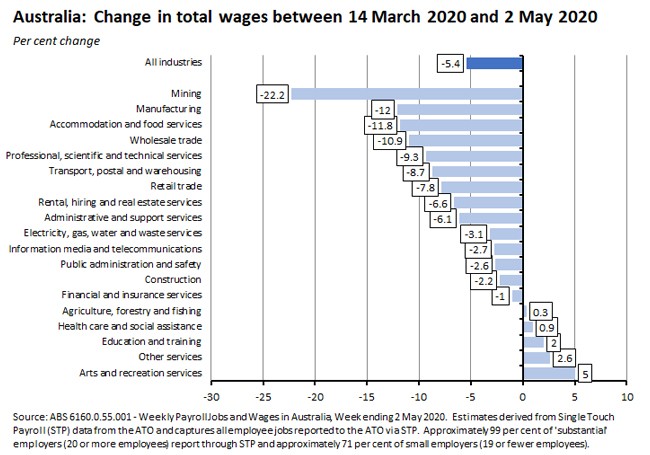

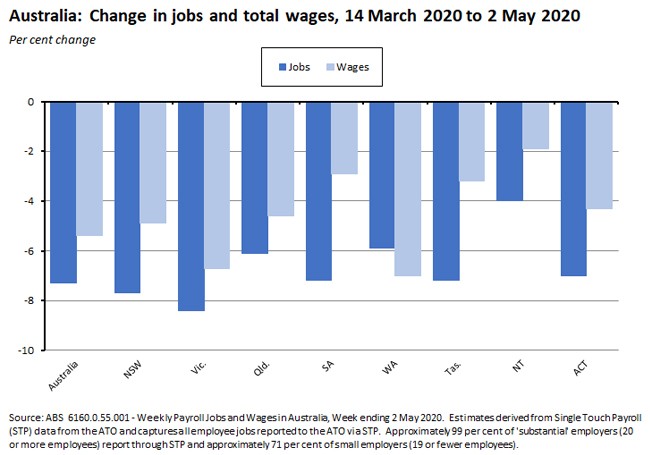

The ABS released new payrolls data, covering the period up to 2 May. Between the week ending 14 March 2020 (the week Australia recorded its 100th confirmed COVID-19 case) and the week ending 2 May 2020, the number of payroll jobs fell by 7.3 per cent while total wages paid declined by 5.4 per cent. Note that the ABS also said that the previous result for total job losses as of the week ending 18 April has now been revised down from 7.5 per cent to 7.1 per cent.

For the two new weeks included in the data, between the week ending 25 April 2020 and the week ending 2 May 2020 the number of jobs dropped by 1.1 per cent, compared to an increase of 0.9 over the previous week, while total wages paid increased by 0.5 per cent in the week ending 25 April and by 0.9 per cent in the week ending 2 May.

By industry, the biggest declines in jobs continue to be in accommodation and food services (down by 27.1 per cent) and arts and recreation services (down 19 per cent), with rental and real estate services (down 12 per cent) now showing the third steepest fall.

The largest declines in total wages paid are in the mining sector (a drop of 22.2 per cent) and manufacturing (a fall of 12 per cent). Notably, total wages paid have now increased in several sectors, including health care and social assistance, education and training, other services, and arts and recreation services.

By State and Territory, the biggest falls in jobs have been suffered by Victoria (down 8.4 per cent) and New South Wales (down 7.7 per cent) while the largest declines in total wages paid have been in Western Australia (down seven per cent) and Victoria (down 6.7 per cent).

For the first time with this new ATO series, the ABS also released data on regional labour markets. These showed that the three the worst hit regions across the country – suffering from double digit job losses – were the Mid-North Coast region in NSW (where the number of jobs was down 11.8 per cent), the Coffs Harbour-Grafton region in NSW (down 11.2 per cent) and the Sunshine Coast in Queensland (down 10.2 per cent).

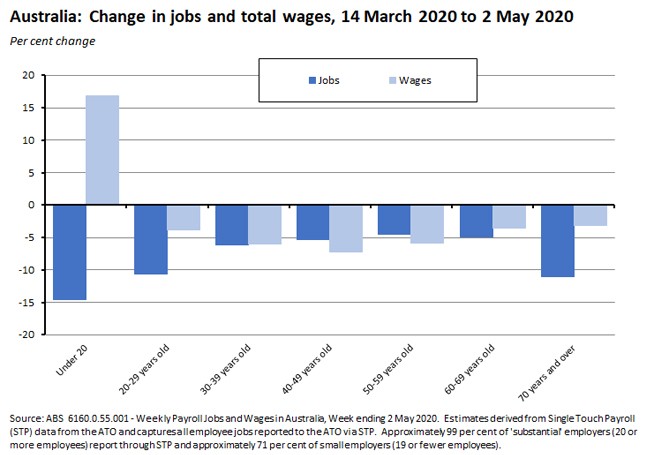

By age, the largest changes were falls in jobs by people aged under 20 (down by 14.6 per cent) and those worked by people aged 70 and over (down 11 per cent), a fall in payments to people aged 40-49 (down 7.3 per cent) and an increase in payments to people aged under 20 (up 16.8 per cent).

Finally, since the week ending 14 March 2020 the ABS reports that jobs worked by females have fallen by 7.1 per cent and those worked by males by 6.9 per cent, while total payments to females have fallen 1.9 per cent and total payments to males have declined 7.6 per cent.

Why it matters:

This latest set of payroll data had a couple of particularly noteworthy features.

- First, there were some signs of a slowdown in the rate of job destruction as the pace of decline across the past fortnight eased relative to the previous fortnight: between 14 March and 18 April, the number of jobs had fallen 7.1 per cent. Adding another two weeks of data ‘only’ took the total decline to 7.3 per cent. To be clear, that is still a terrible result. But the slowing pace of decline is welcome.

- Second, total wages paid increased over the past fortnight. While the total wage bill had fallen by 8.2 per cent over the 14 March – 18 April period, that decline had moderated to a 5.4 per cent decrease for the 14 March – 2 May period.

Those two developments also suggest that the impact of the JobKeeper scheme may now be starting to show up in job numbers and in wages paid. For example, two of the hardest hit sectors – accommodation and food services and arts and recreation services – both added jobs over the past two weeks. Moreover, total wages paid also increased in both sectors over the same two week period and in the case of arts and recreation services, total wages paid have now increased over the entire 14 March – 2 May period, a pattern that now extends to several other sectors. The larger increase in payments to people aged under 20 is also likely a reflection of the impact of JobKeeper.

What happened:

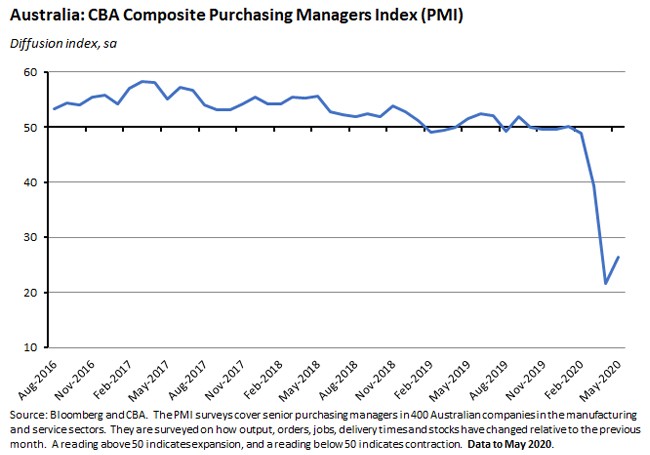

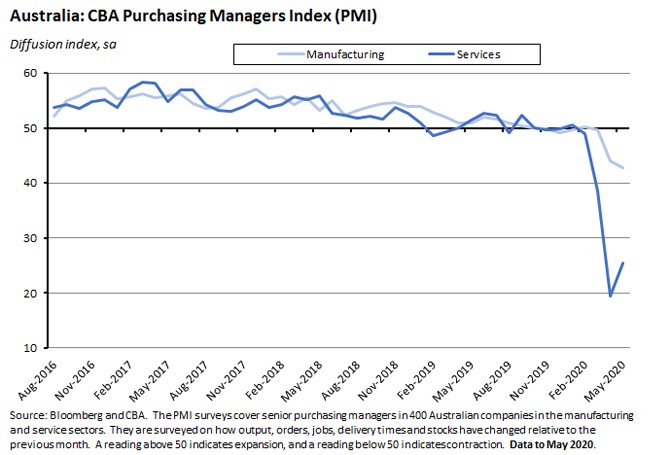

The CBA ‘flash’ composite Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) rose from 21.7 in April to a preliminary estimate of 26.4 in May.

That modest improvement reflected a recovery in the services PMI, which rose from 19.5 to 25.5. The manufacturing PMI fell from 44.1 to 42.8.

Why it matters:

PMI readings measure the change in business activity relative to the previous month, with an index value of 50 separating expansion from contraction. That means the flash estimates for May are consistent with continued contraction in both services and manufacturing following April’s fall in activity, but with the position of the services sector looking particularly dire.

What happened:

The RBA published the minutes of the 5 May 2020 Monetary Policy Meeting of the Reserve Bank Board. In the minutes, members of the Board ‘agreed that the Bank's policy package was working broadly as expected.’ In their judgement, the measures had:

- Helped to lower funding costs and stabilise financial conditions, thereby supporting the economy.

- Contributed to a significant improvement in the functioning of government bond markets.

- Moved the three-year Australian Government bond yield to the RBA’s target of around 25 basis points.

The minutes also discussed the RBA’s decision to broaden the range of eligible collateral for domestic market operations. That eligible collateral now includes Australian dollar securities issued by non-bank corporations with an investment grade credit rating. According to the minutes, this was intended to ‘bring the treatment of corporate bonds in the Bank's collateral framework into close alignment with that of bank debt. It would improve the liquidity characteristics of some corporate bonds, helping to facilitate the smooth functioning of the market,’ adding that ‘the proposed approach was consistent with the collateral frameworks of the major central banks, which accept corporate paper under repurchase agreements (repos), and…would not have a material impact on the Bank's risk profile…[as the BRA would]… not be purchasing corporate paper on an outright basis, but only under repos.’

The minutes also included an assessment of financial stability risks, with the focus on the resilience of Australian households and the commercial property sector. In the case of the former, the minutes note that while around one-third of households with mortgages have prepayment buffers of three years or more, a smaller share have no mortgage prepayment buffer and are more susceptible to financial stress. Board members also foresaw problems for the commercial property sector, especially for office and retail property, where a large amount of new office space is expected to be completed in Sydney and Melbourne this year. Demand is unlikely to match this rising supply, which will push vacancy rates up and office rents down. That in turn is likely to lead to lower valuations, creating stress for leveraged property investors and developers. The discussion noted that retail property was already experiencing rising vacancies and falling capital values prior to the current downturn and that social distancing measures were likely to exacerbate these strains.

Finally, the reported discussion also reiterated that under all three scenarios for the Australian economy considered by the Board and presented in May’s Statement on Monetary Policy, the labour market was expected to have ongoing spare capacity, and inflation was expected to be below two per cent over the following few years, supporting the case for maintaining the current policy stance.

Why it matters:

Along with a warning about emerging signs of financial stress in parts of the economy, the minutes mostly confirmed, albeit in a little more detail, the message from the 5 May policy statement: the key elements of the RBA’s 19 March 2020 policy package (a cash rate at the effective lower bound of 0.25 per cent, yield curve control (YCC) pegging the three-year government bond yield at around 0.25 per cent, and a term funding facility to support lending and cap funding costs) are all set to remain in place for some time yet, with rock bottom policy rates in particular likely to be with us for several years.

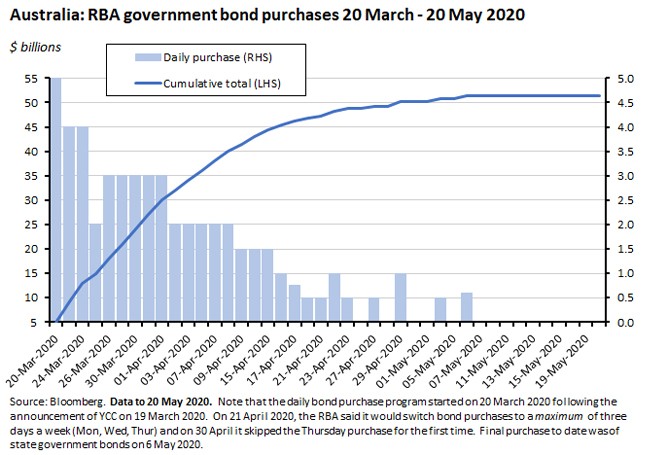

They also confirmed that the winding back of the RBA’s purchase of government bonds as part of YCC does not reflect any reduced commitment to that target, but rather reflects the central bank’s success in guiding yields to where it wants them. The RBA launched a daily program of buying government bonds on 20 March but then on 21 April announced it would scale back its purchases to just three days a week (Mondays, Wednesdays and Thursdays) and by 30 April it was skipping a Thursday purchase. The last purchase of federal government bonds to date came on 4 May and of State and Territory bonds on 6 May.

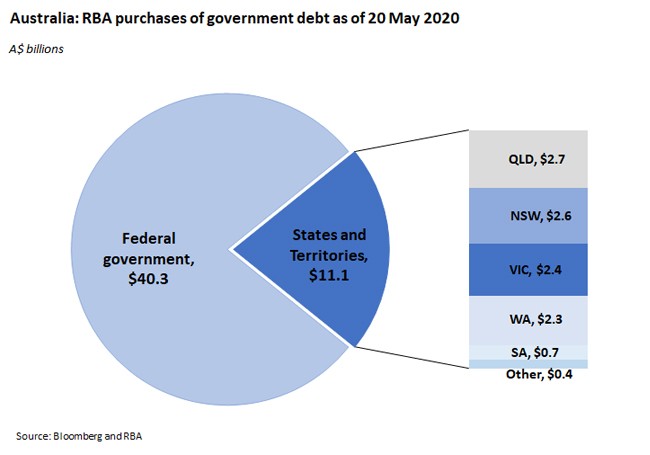

To date, the RBA has purchased a total of $51.35 billion of government debt, of which $40.3 billion is federal government paper and $11.1 billion is State and Territory debt.

Given the ramp up in debt issuance required to fund ballooning fiscal deficits, there had been some speculation that the RBA’s moves to taper its bond purchase programs would have to be reversed in the face of a marked increase in supply. To date, however, there has been no sign of that, suggesting that the RBA has been successful in establishing both the credibility of the YCC framework and the stability of the government bond market. But this week’s minutes also noted that the central bank stands ready to ‘scale up these purchases again, if necessary, to achieve the yield target and ensure bond markets remain functional.’

What happened:

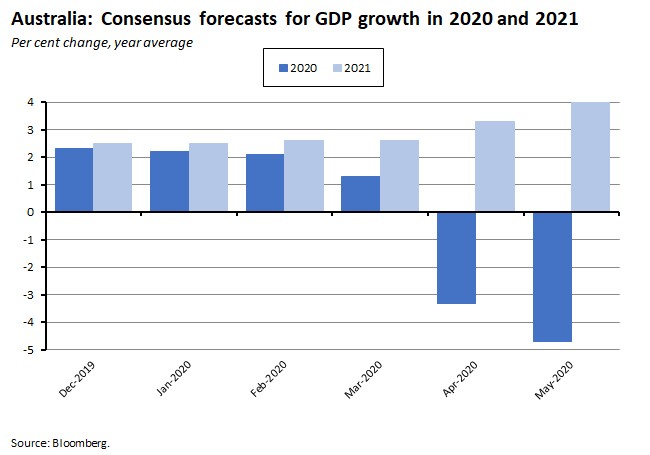

The average forecast based on the latest survey of economic forecasts collected by Bloomberg this month suggests that the Australian economy will shrink by 4.7 per cent this year before growing by four per cent in 2021.

The survey pulled together the forecasts of 37 economists and was conducted between the 14th and 19th of May.

Why it matters:

All forecasts right now come with large health warnings attached (no pun intended). Still, tracking the evolving consensus forecast provides another window into how views about economic prospects are shifting, with the pace of change arguably of more interest for now than the absolute level of the forecast.

. . . and what I’ve been following in the global economy

What happened:

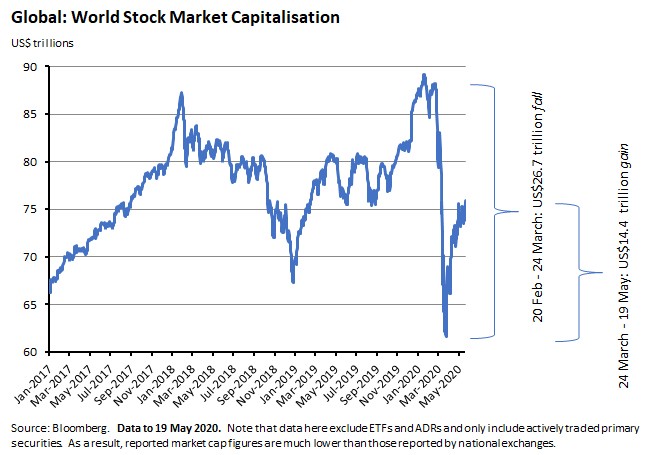

Despite a run of bad news on the global economy, including record high unemployment rates, the prospect of record falls in GDP, major economies including Japan, Germany and France slumping into recession in the first quarter of this year, and the United Nations warning that its Human Development Index is poised to go backwards for the first time since 1990, global stock markets have been remarkably resilient over recent weeks. After the early days of the pandemic saw global stock market capitalisation tumble by almost US$27 trillion between 20 February and 24 March, markets have since clawed back more than US$14 trillion of those losses. So, very much still under water, but by much less than they were.

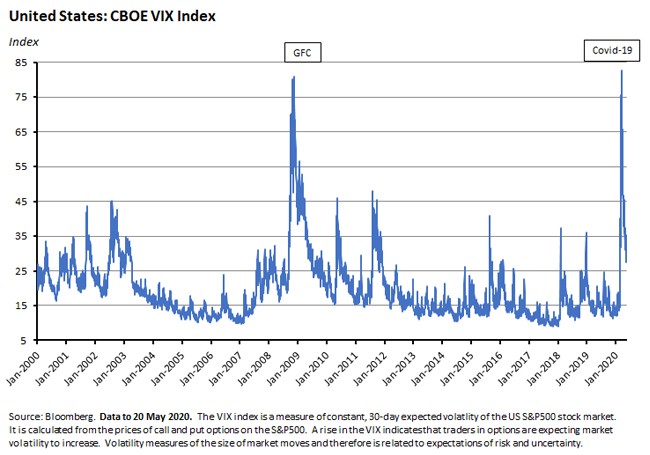

Meanwhile, measures of market volatility, including the so-called fear index or VIX, have retreated from their March highs and are now well below GFC-like levels.

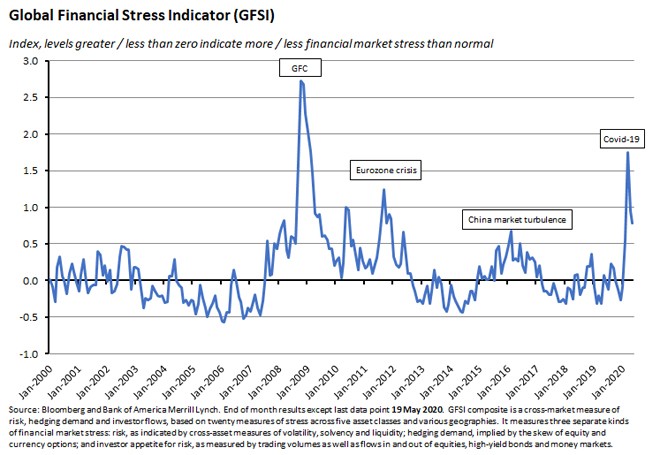

Other measures of market stress are also currently painting a much more reassuring picture than they were a couple of months ago, when financial Armageddon appeared to be looming.

Why it matters:

Notoriously, interpreting the stock market is at least as much about creative story-telling as anything else: sceptics keen to cite our human ability to finding meaning in instantaneously generated narratives often refer to the willingness of market analysts to tell post-hoc stories about why the market rose or fell on any given day (yes, I know, says the economist). So, caveat emptor.

Still, the discrepancy between the real and financial economies now is a striking feature of the landscape, so it’s interesting to think about what it might be telling us. Here are a few possibilities:

- The initial market correction back in mid-March was ‘too large’ as it included a significant amount of overshooting due to collective panic and uncertainty around the prospect for (successful) official intervention. That process of overshooting is now being reversed.

- That market panic was stemmed by unprecedented financial market support from central banks operating on a massive scale, led by the US Fed. A ‘Powell Put’ means that the Fed is viewed as having every investor’s back. Large-scale fiscal support could be added to the mix here, too.

- Markets are forward-looking and – now that the news on the rate of increase of COVID-19 has apparently improved across many economies – are pricing in the expected recovery rather than the near-term pain. (See also the improving consumer confidence numbers discussed above.) Of course, they could still be wrong about the nature of that recovery…

- Related, very bad tail-risk outcomes (1918 Spanish Flu-like death tolls, a complete financial market collapse) are now back to being priced as, well, extremely unlikely tail risks, which wasn’t the case in March.

Perhaps add in some periodic bouts of irrational exuberance? And see also the Cassidy piece in the readings below.

What I’ve been reading

ANZ Bluenotes introduces the bank’s latest Stateometer, which captures the first CVC shockwaves hitting the state economies in the opening quarter of this year.

Greg Earl recaps the recent discussion on diversification and international economic sovereignty in the context of Australia’s ongoing trade disputes with China.

The ABS has started a new series of notes looking at economic measurement during COVID-19. The first summarises its approach to classifying JobKeeper payments in ABS Economic Statistics along with the treatment of the boosting cashflow to employers measure.

RBA Governor Philip Lowe’s opening remarks to the FINSIA Forum.

The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) reviews (pdf) the state of the government’s finances as of March this year in what the PBO says will be the first in a series of new monthly publications that will track the impact of COVID-19 and the associated policy response on the fiscal position. The numbers show that while fiscal revenue in March 2020 was little changed relative to the position in March 2019, expenditures were $8.7 billion higher than in the same month in the previous year. That mostly reflected a $6.5 billion increase in social security and welfare payments, driven in part by the policy response to the CVC. As a result, the year to date fiscal deficit rose to $22 billion as of March, well up on the previously expected $13.8 billion deficit.

Karen Andrews, the Minister for Industry, Science and Technology, spoke at the Press Club on the Australian manufacturing sector. A key message was that ‘While COVID-19 has brought issues such as sovereign capability to the forefront and, frankly, exposed gaps in our manufacturing, I am not suggesting that complete self-sufficiency should be our goal…But it is clear we can’t just rely on foreign supply chains for the essential items we need in a crisis.’

The Economist magazine considers the potential economic benefits of travel bubbles.

In the New Yorker, John Cassidy asks why small investors have been jumping into US share markets in growing volumes: belief in the narrative of a V-shaped equity market recovery, faith that the US Fed has their backs, or a substitute for sports betting for punters looking for an alternative?

This poll of institutional investors offers one interesting take on how perceptions about the likely pace of recovery – and the chance of more fundamental change – varies across (US) sectors. They are most optimistic about a quick recovery in IT, communications and health care, and think a slow recovery is more likely in real estate, energy and firms catering to consumer discretionary spending. The sectors expected to see the most fundamental change are health care, real estate and energy.

Reinhart and Rogoff explain why this time is different.

Foreign Policy has been running collected thought pieces from ‘leading global thinkers.’ The most recent looks at the expansion of state power (predictions include more state surveillance, more industry policy, and more scope for corruption and graft but also greater rewards for good governance). Previous collections consider the economy, the world and cities.

Martin Wolf weighs up the prospects of a post-pandemic surge in inflation and concludes that while the chances of inflation have risen, they are still modest.

Benjamin Cohen argues that the US dollar’s supremacy has been shaken by COVID-19. This seems somewhat counterintuitive to me at this point, since one early lesson was that Fed support via dollar swap lines was critical for global financial stability (something Cohen acknowledges up front). But maybe policymakers and businesses will take that lesson in vulnerability to heart?

A proposal to use age as a guide to the labour market policy response to the CVC.

The BIS Bulletin has a piece that takes a look at health and privacy issues across countries in the context of deploying technology to fight the pandemic.

The WSJ has a simple primer on the maths of COVID-19 which plugs in some of the newer estimates. And here’s a Bloomberg piece that summarises a range of COVID-19 models. My key takeaway from this latter one – none of the models reviewed are particularly good at prediction, but that is only one of their intended functions.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content