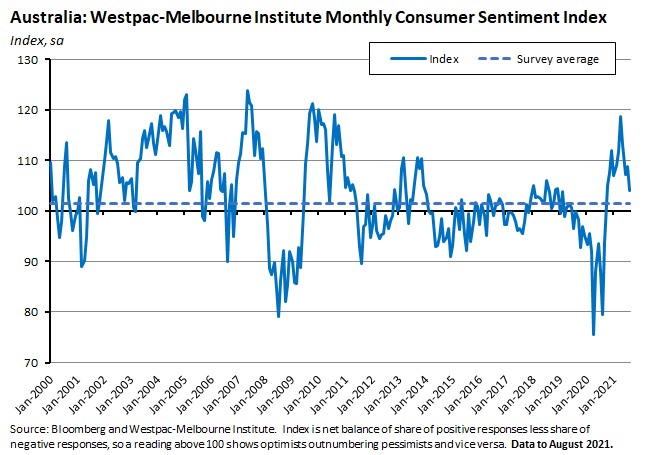

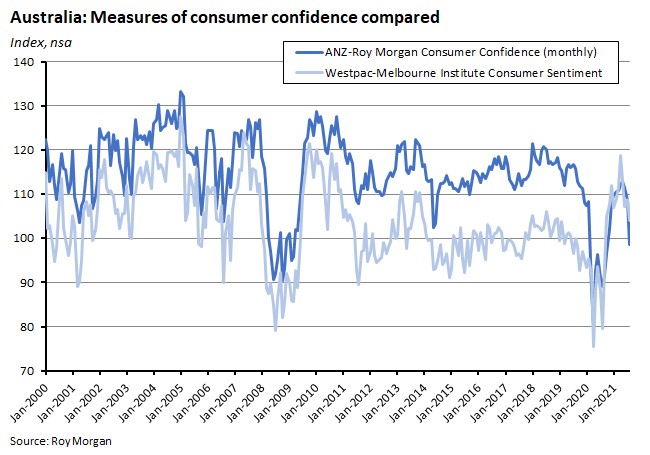

A light week on the Australian data front showed the Delta variant and state lockdowns again weighing on households and businesses. The monthly Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index of Consumer Sentiment fell 4.4 per cent in August, dragged down by a big drop in Victoria and a smaller but still substantial decline in New South Wales.

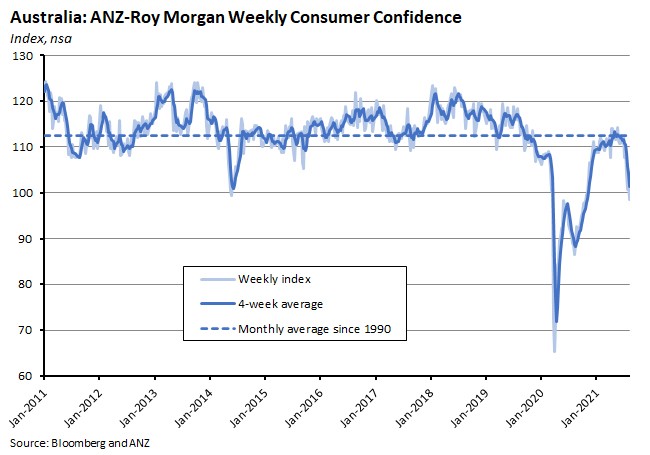

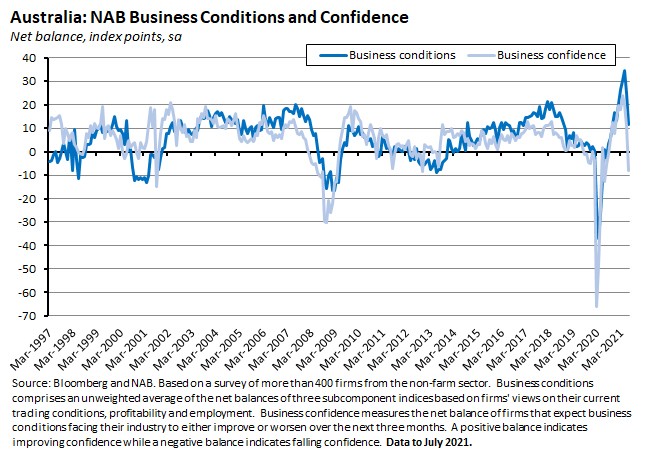

On this basis, consumer sentiment has now fallen to its lowest level since September 2020. That said, the index is still some 38 per cent higher than the pandemic low set back in April 2020. It also remains in positive territory overall as more respondents continue to feel optimistic than pessimistic. At the same time, the weekly ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index dropped 3.1 per cent in the week to 8 August, falling below 100 for the first time since November last year. Once again, and despite recent falls, confidence is still well above where it was during the early months of COVID-19 last year. Overall, although consumers are clearly worried by recent developments, there has nevertheless been enough prior progress in terms of the economic recovery and the vaccine rollout to forestall any return to the levels of fear and uncertainty that marked the opening months of the pandemic. Turning from households to businesses, the NAB monthly survey showed business confidence in July plummeting by 19 index points over the month while business conditions slumped by 14 points. NAB’s measure of business confidence is now back in negative territory for the first time since September last year, is at its lowest level since July last year and is also well-below the series average. Business conditions have fallen to their lowest level since October 2020, but in this case the economic momentum built up during Australia’s earlier recovery from last year’s lockdowns and the consequent sizeable run-up in conditions mean that, even after July’s big decline, business conditions overall remain in positive territory.

This week we also take a more detailed look at the RBA’s August Statement on Monetary Policy, released last Friday.

As well as a selection of commentary around the major new IPCC report on climate change, the week’s round up of readings includes Australian politics’ susceptibility to the temptations of ‘pork barrelling,’ five years of Australian economic diplomacy, the relationship between lockdowns and retail sales, carrots vs sticks as incentives for vaccination, five lessons on the best ways to fight pandemics, the post-pandemic US business boom, Dambisa Moyo on how boards work, and the case for free markets.

Finally, stay up to date on the economic front with our AICD Dismal Science podcast .

Listen and subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

The Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index of Consumer Sentiment (pdf) fell 4.4 per cent in August, taking the index down to a reading of 104.1

All five index components fell over the month, with the biggest falls for ‘economic conditions next 12 months’ (down 8.3 per cent), ‘time to buy a major household item’ (down 7.2 per cent) and ‘family finances next 12 months’ (down 2.7 per cent).

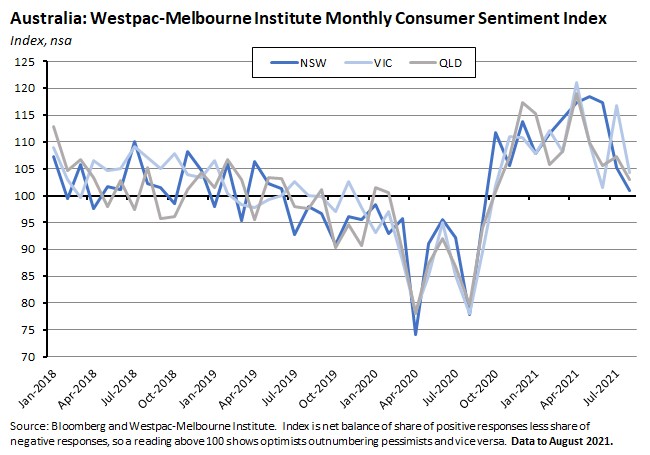

By state, the biggest fall in sentiment was in Victoria (down 10.8 per cent in August after having jumped up by 15 per cent in July). Confidence was down a further 4.1 per cent in New South Wales, meaning that state’s index is now 14.8 per cent off its May high, and sentiment also fell four per cent in Queensland. But there were gains in South Australia (up 9.1 per cent) and Western Australia (up 4.1 per cent).

Separately, the ‘time to buy a dwelling index’ dropped 8.3 per cent in August and is now more than 17 per cent down over the year. And although the House Price Expectations Index also dipped 1.6 pe cent over the month it is still up more than 112 per cent in annual terms, suggesting that high house prices are now weighing on consumer demand.

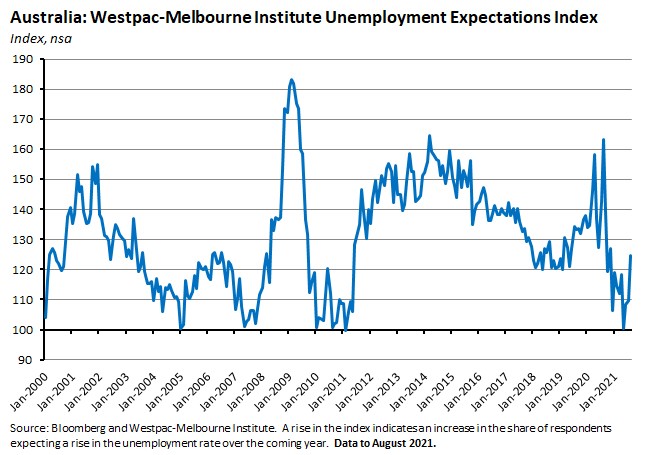

Finally, the Unemployment Expectations Index bounced by 13.7 points in August, indicating a sharp rise in the share of respondents expecting a rise in the unemployment rate over the year ahead.

Why it matters:

Consumer sentiment has now fallen to its lowest level since September 2020 while at the same time remaining significantly above both that month’s level (an index value of 93.9) and the pandemic low of April 2020 (an index value of 75.6). That suggests two things: first, that lockdowns and health concerns continue to take a significant toll on sentiment; but, second, that the level of consumer sentiment remains significantly higher than it was during the early months of COVID-19 last year, implying that households still feel much more confident now than they did back then. At the same time, the jump in the Unemployment Expectations Index also indicates that households are increasingly worried by the potential labour market fallout.

August’s survey was conducted between 2 and 7 August and therefore captured the ongoing lockdown in Greater Sydney, the Southeast Queensland lockdown and the start of the Victorian lockdown. Unlike the NAB business survey for July (see below), however, the dispersion of sentiment readings across states – with sentiment up in Western Australia and South Australia – suggests that cross-state spillover effects via the confidence channel were limited.

What happened:

The ANZ Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index fell 3.1 per cent last week, dropping to a value of 98.6.

Three of the five subindices fell over the week to 7-8 August: ‘current financial conditions’ (down 5.7 per cent), ‘future financial conditions’ (down 4.8 per cent) and ‘time to buy a major household item’ (down 8.3 per cent). ‘Current economic conditions’ (up 3.8 per cent) and ‘future economic conditions’ (up 0.9 per cent), both rose following three weeks of declines.

Confidence was down 7.8 per cent across Queensland and 7.5 per cent in Brisbane and also dropped three per cent in Victoria and 1.6 per cent in Melbourne. Confidence in New South Wales remains at the lowest level across all states, although last week the index was up 3.7 per cent in Sydney and 2.1 per cent in the rest of the state.

Why it matters:

New lockdowns in Queensland and Victoria saw the overall ANZ-Roy Morgan confidence index fall below 100 and slip into pessimistic territory for the first time since November last year. That was despite an increase in reported confidence New South Wales over the week, with the latter likely reflecting a combination of the easing of some restrictions on the construction industry and an increase in the vaccination rate.

The story here looks broadly consistent with the monthly data discussed in the previous story.

What happened:

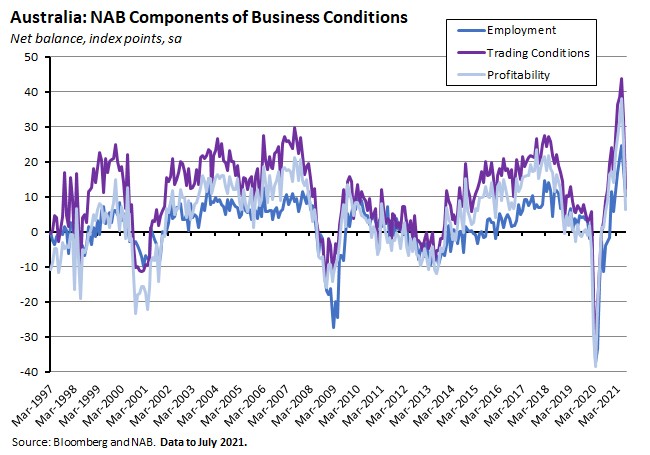

The NAB Monthly Business Survey for July 2021 reported that business conditions fell by 14 points to +11 index points in July after having fallen by nine points in June. Business confidence slumped 19 points to -8 index points.

As had been the case in June, last month’s decline in business conditions was also driven by falls across all three subcomponents, with particularly steep declines in the trading (down 20 index points) and profitability (down 19 points) subindices. The employment subindex also fell, dropping eight points.

Developments in New South Wales dominated the results last month, with the state suffering big hits to confidence and conditions. NSW business conditions plummeted 31 points to +2 index points with large falls across all subcomponents: Trading conditions declined 37 points to + 5 index points, profitability fell 29 points to +1 index points and employment was down 20 points to +2 index points. At the same time, business confidence slumped by 27 points to -21 index points, the weakest reading across the states.

While the decline in business conditions was steepest in New South Wales, conditions fell across all mainland states (noting that Tasmania reported a rise in conditions), with South Australia also experiencing a very large fall. Business conditions also softened in all industries except for mining, with particularly large falls in transport & utilities and recreation & personal services (down 29 and 25 points respectively).

Again, while the drop in business confidence was also largest in New South Wales, the indicator was down across all states (although Queensland is the only other state where confidence has moved into negative territory). By industry, transport & utilities, manufacturing and finance, and business & property all suffered substantial declines in business confidence over last month and, along with wholesale, retail and rec & personal services, are now all back in negative territory. Mining confidence is a strong positive outlier to this story with an index reading of +18 index points while construction confidence also remains in positive territory.

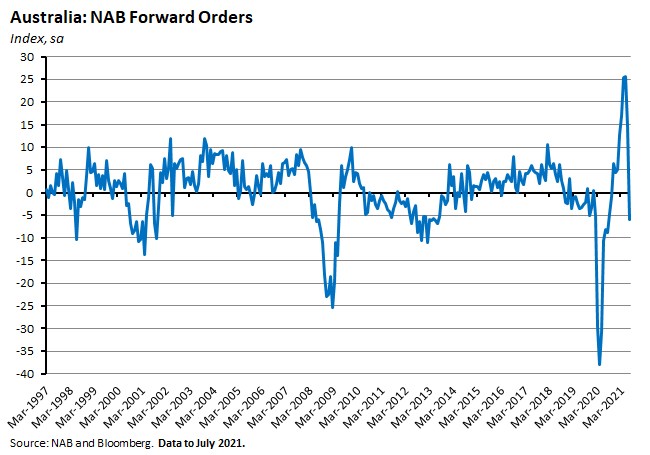

Forward orders saw a sharp decline (down 21 index points) in July, falling back into negative territory for the first time since October last year.

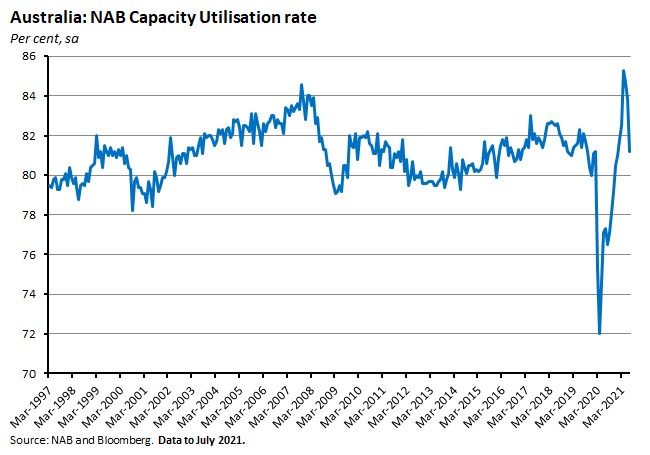

The rate of capacity utilisation also eased further, slipping to 81.3 per cent. Utilisation rates are now back below their pre-COVID level in New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia.

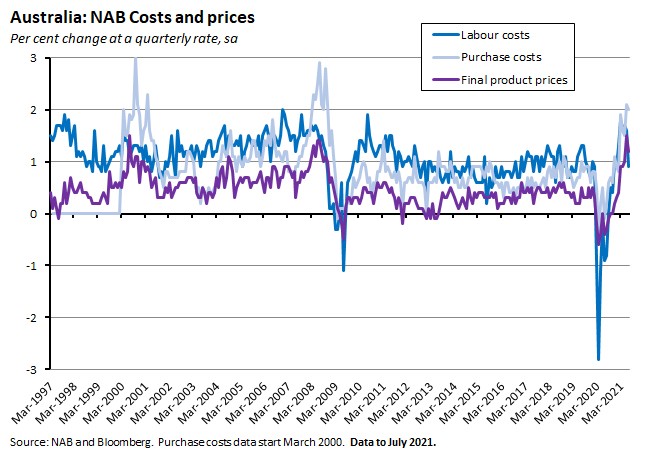

Inflation indicators in July all softened relative to their June readings, although the rate of growth of purchases costs and final product prices both remain high compared to the experience of recent years.

Why it matters:

July’s slump in the index means that NAB’s measure of business confidence is now back in negative territory for the first time since September last year, is at its lowest level since July last year and is also well-below the series average. In contrast, the scale of the preceding run-up in business conditions means that, even after last month’s big decline, conditions remain in positive territory and above the long-run average for the series. Even so, the business conditions index has still dropped to its lowest level since last October.

The sharp declines in both business conditions and business confidence last month reflect the impact of rising COVID case numbers and state lockdowns. NAB’s survey was conducted between 20 and 30 July, a period which saw New South Wales remain in lockdown and South Australia undergo a seven-day lockdown. And while Victoria had re-opened by then, that state had been under lockdown for some of the preceding month. July’s readings also suggest the presence of some negative spillover effects across state borders, while the sharp fall in forward orders and the moderation in the rate of capacity utilisation both point to ongoing weakness.

What happened:

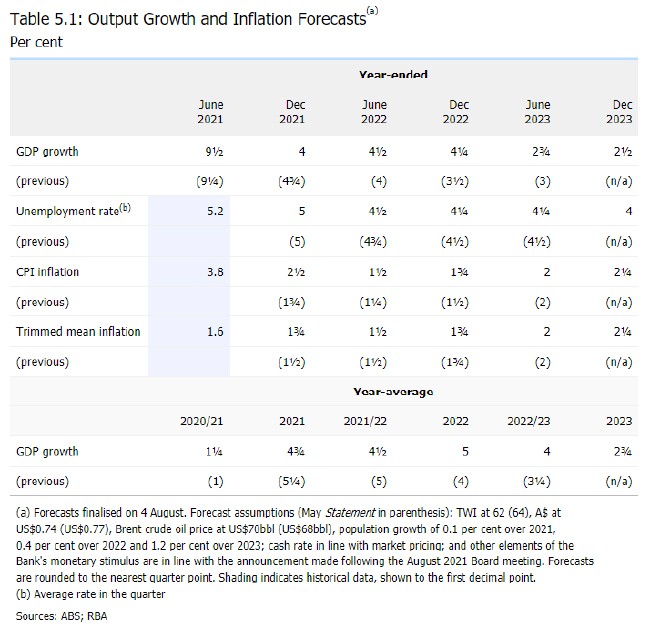

Last Friday, the RBA published the August 2021 Statement on Monetary Policy (SOMP). The SOMP updates the RBA’s views on the economy and includes new forecasts that now run until December 2023. The same day also saw RBA Governor Philip Lowe’s testimony to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics.

In his opening comments to the House, Governor Lowe summarised August’s SOMP as encompassing five key themes: (1) Australia’s economic recovery has been quicker and stronger than the RBA expected; (2) But real GDP will now likely contract in the September quarter due to state lockdowns, particularly in Greater Sydney; (3) The economy is expected to bounce back quickly once restrictions are eased; (4) While there have been upside surprises in terms of output and employment, that has not been the case for wages and prices, where the RBA expects growth in both variables to be subdued for some time yet; and (5) the RBA’s monetary policy measures are providing the economy with significant support.

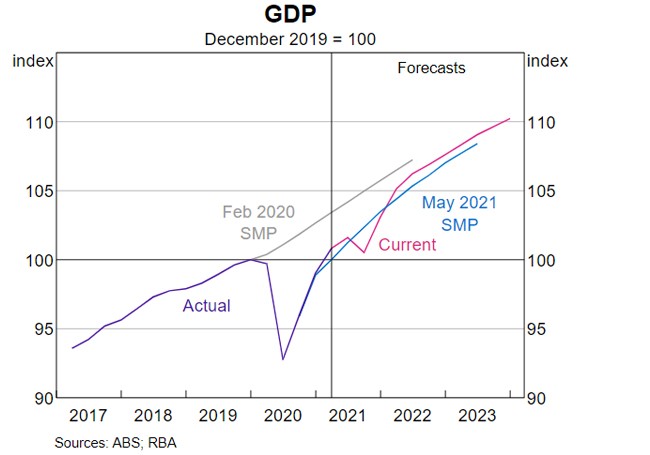

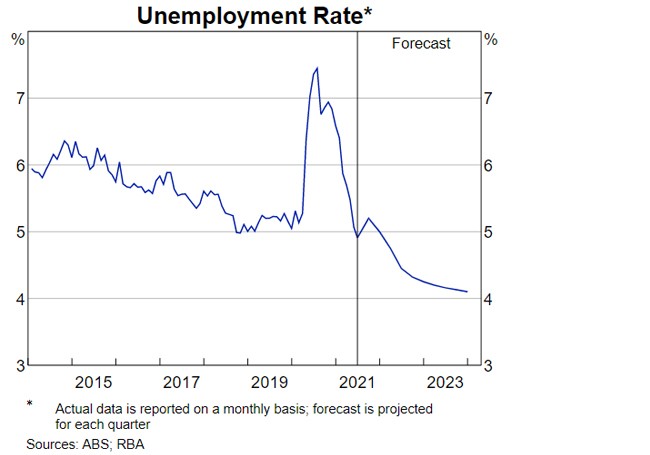

Starting with the first of these, the SOMP notes that by the end of the March quarter this year, Australia’s level of real GDP was already above pre-pandemic levels, labour underutilisation had declined, and at 4.9 per cent the June unemployment rate was below its pre-pandemic levels. To date, both output and especially the labour market have done considerably better than the RBA was expecting in earlier iterations of its forecasts.

In the near term, however, the RBA concedes that this progress will be interrupted by the recent outbreaks of the Delta variant and the associated state lockdowns, which the SOMP suggests will see output in the September quarter contract by at least one per cent (instead of increasing by a similar amount as projected pre-lockdown). Rather than averaging the 5.25 per cent growth predicted in May’s SOMP, August’s forecast now has growth in real GDP averaging 4.75 per cent this year, while year-on-year growth in the December quarter has been scaled back from May’s forecast 4.75 per cent to four per cent now.

Source: RBA

The new SOMP also forecasts the unemployment rate to increase over the September quarter this year, although the rise is expected to be modest with the main impacts on the labour market expected to come through a substantial decline in average hours worked by employees (including an increase in those on zero hours) and a decline in participation. As a result, the unemployment rate forecast for the December quarter has been left unchanged at five per cent.

Source: RBA

Looking beyond short-term economic dislocation arising from the Delta variant, the central scenario presented in the SOMP draws on previous domestic and international experience with lockdowns to argue that ‘private demand and the labour market quickly recover when containment measures are relaxed and cases of the virus remain low.’ It also assumes that ‘recent outbreaks can be brought under control soon and further outbreaks are limited’, and that the outlook will also benefit from ‘significantly higher vaccination rates.’ As a result, the forecast for average GDP growth across 2022 has been upgraded, from four per cent in the May 2021 SOMP to five per cent in the August 2021 Statement, with year-end growth up from 3.5 per cent to 4.25 per cent. Similarly, the forecast for the unemployment rate by the December quarter of next year has been trimmed from 4.5 per cent to 4.25 per cent.

Source: RBA

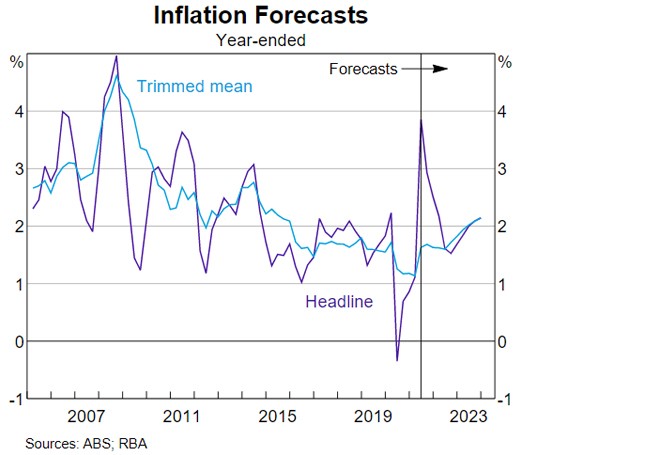

Those upgrades to the growth and labour market outlook are expected to have only a modest impact on wage growth, with increases in the wage price index (WPI) predicted to be running at 2.5 per cent by the end of next year and 2.75 per cent by December 2023. The RBA notes that reports from its liaison team suggests that wages growth in many firms is now returning to around its pre-pandemic norm of two-to-2.5 per cent this year, but not to anything stronger than this. Against that backdrop, underlying inflation is now predicted to ‘pick up a little more quickly than previously anticipated to be a little above two per cent by the end of 2023.’

Source: RBA

In terms of monetary policy, the August SOMP notes the RBA Board considered whether it should continue with the change in the rate of bond purchases it announced at its July meeting, or if it should instead delay the change. While accepting that recent development have interrupted the recovery, and that as a result many firms and households were ‘facing difficult conditions’, the RBA’s view was that the need for any additional support was likely to be concentrated in the short term, with the economy set to return to strong growth next year, and that fiscal policy was better placed to provide the necessary support to offset ‘a temporary, localised reduction in incomes.’ Otherwise, the Board remains ‘committed to maintaining highly accommodative monetary conditions to support a return to full employment in Australia and inflation consistent with the two-three per cent target.’ Despite the forecast upgrades noted above, it still thinks that this ‘will not be until 2024.’

The projections summarised above refer to the RBA’s baseline scenario. This assumes that ‘the domestic vaccine rollout accelerates in the second half of the year, reducing the frequency and severity of lockdowns and allowing the international border to be reopened gradually from mid-2022…the Sydney lockdown extends through the September quarter…the lockdown in south-east Queensland ends as planned with some further brief (and less severe) restrictions assumed to occur in the December quarter.’ The SOMP also discusses two alternative scenarios: one in which ‘the spread of the Delta variant results in more extended and widespread lockdowns and the international border reopens more slowly’ and one where ‘the virus is contained more quickly than envisaged in the baseline scenario.’ The former is associated with slower growth, a higher unemployment rate (one that is still above five per cent at the end of the forecast period) and weaker inflation (underlying inflation is still in the range of 1.25 per cent to 1.5 per cent through to 2023). The latter sees a faster decline in the unemployment rate and a rise in inflation to the upper half of the target band by the end of 2023.

While health developments are the source of the main upside and downside risks to the economic outlook, the RBA also notes that another key uncertainty is how wages and prices respond to an unemployment rate that is forecast to fall to four per cent by end-2023, with the SOMP emphasising that there is little recent experience here to guide the central bank: since the 1970s, a level of unemployment this low has only been experienced very briefly, in 2007/08 at the peak of the mining investment boom. Other risks flagged by the Statement include capacity constraints in other parts of the economy, the outlook for housing and financial asset prices, and the willingness of households to consume out of wealth and savings.

Why it matters:

The main messages from last week’s Statement on Monetary Policy had already been flagged by the brief statement accompanying the August meeting of the RBA board: the central bank expects the Australian economy to suffer a short-term hit in the third quarter but by next year judges that it will have returned to relatively robust growth, albeit growth that is not quite robust enough to see Martin Place change the prediction of no rise in the cash rate before 2024. Governor Lowe was even more explicit about the preconditions for any monetary policy normalisation in his opening testimony to the House Economics Committee, noting that:

‘As I have said previously, the Board will not be increasing the cash rate until inflation is sustainably in the two to three per cent range. We want to see results on inflation before we move, not a forecast of inflation in the target range. It will not be enough for inflation to just sneak across the two per cent line for a quarter or two. We want to see inflation well within the target band and be confident that it will stay there.’

The Statement also confirms that the nature of the economic outlook remains heavily conditional on the pandemic and on the vaccine rollout, containing as it does both upside and downside scenarios. Given the central bank’s relatively upbeat view on short-term prospects and the economy’s ability to manage the ongoing challenges posed by the Delta variant, risks to the RBA’s baseline forecasts currently look skewed towards the downside, particularly in the near term.

What I’ve been reading . . .

- For those who would like even more insight into the RBA’s thinking that that already provided by last week’s Statement on Monetary Policy and the Governor’s opening statement to the House Standing Committee on Economics (both discussed above), Hansard’s record of the subsequent discussion between the Governor and the House Committee is also available. Other topics covered in that report include the impact of migration on wages, how the RBA measures economic dynamism, the transparency of pay within the central bank itself, and the implications of Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism compliance for banking in the South Pacific.

- How does Australia’s health care system stack up in international comparison?

- Why is Australian politics so susceptible to ‘rorts’ or ‘pork barrelling’ and what might be done to fix the system?

- A Lowy Institute Analysis on Australia and the growing reach of China’s military and the implications of ‘the greatest expansion of maritime and aerospace power in generations.’ One key conclusion: ‘The prospect of Chinese military action against Australia remains remote. But China has the military and industrial potential to field a long-range power projection capacity that would dwarf anything Japan threatened Australia with during the Second World War.’

- And from Lowy’s Interpreter blog, Greg Earl looks back on five years of analysis of economic diplomacy through the prism of five key themes: the China conundrum, the business of aid, finding Indonesia, team Australia and guns or butter.

- ANZ Bluenotes on lockdowns and retail spending: expect bad news in September but also the possibility of a strong bounce back in Q4 (assuming restrictions end by then).

- Melbourne Institute survey data suggests that financial incentives such as cash payments may have only a limited impact on Australians’ willingness to be vaccinated, and vaccine passports may not do much better. Related, this FT Big Read examines carrots vs sticks as a way to persuade the unvaccinated.

- Five lessons on the best policies to fight pandemics: (1) stringent and early lockdowns – when the number of cases is low – seem to be more efficient at curbing case numbers and reducing economic costs; (2) There is some evidence that international travel restrictions have the highest benefit-to-cost ratio from a menu of measures aimed at containing infections, followed by limits on the size of gatherings and cancelling public events; (3) there’s no consensus on geographical targeting although many models argue for targeting by age and type of job; (4) even absent lockdowns, voluntary social distancing imposes economic costs, although countries with more stringent lockdowns have experienced sharper falls in GDP; and (5) relaxing lockdowns should be done gradually even during vaccine roll-outs.

- The Working Group 1 report for the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report covers the physical science basis, presenting ‘the most up-to-date physical understanding of the climate system and climate change.’ It ‘provides new estimates of the chances of crossing the global warming level of 1.5°C in the next decades, and finds that unless there are immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, limiting warming to close to 1.5°C or even 2°C will be beyond reach.’ The full report is close to 4,000 pages but there is a rather more digestible (albeit politically pre-approved) 42-page Summary for Policymakers (pdf) and a two-page collection of headline statements (pdf) extracted from that summary. There is also a two-page regional summary (pdf) for Australasia that projects continued rises in sea level (leading to increased coastal flooding and shoreline retreat), decreasing snow cover and depth, and an increase in the intensity, frequency and duration of fire weather events (all high confidence projections) as well as an increase in heavy rainfall and river floods and in sand storms and dust storms (medium confidence projections).

- Commentary on the IPCC’s work from the Economist, FT, Bloomberg and http:WSJ.

- An IMF blog on managing the political economy of climate change policies.

- A roundup from IHS Markit on the latest global PMI survey results suggests that the global economy expanded at a solid rate in July although growth moderated again relative to the 15-year high reached in May 2021. At the same time, divergences in global growth widened last month, with Delta hitting many emerging economies harder than advanced economies.

- Barry Eichengreen doubts that central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) will undermine the central role of the US dollar. That would, he argues, require CBDCs to be interoperable, and the preconditions for making this work remain formidable.

- Grep Ip says China wants manufacturing, not the internet, to lead its economy. In his opinion, Beijing’s view is that while some technology might be nice to have (think social media, e-commerce), the tech China needs to have to buttress its national power includes semiconductors, electric batteries, commercial aircraft and telecoms equipment. It’s a very different approach to setting priorities to that implied by e.g. relative stock market valuations

- This piece in the Atlantic argues that the post-pandemic business boom in the United States (US entrepreneurs launched 500,000 more new businesses considered likely to hire employees from mid-2020 to mid-2021 than they did from mid-2018 to mid-2019) suggests that fiscal policy can stimulate not just economic activity but also entrepreneurship. Other ‘positive’ pandemic effects include that for some businesses the shift to WFH increased start-up speeds and cut costs, while the rise of Zoom reduced the impact of geography and made securing meetings easier.

- One hypothesis regarding the current global financial environment is that we’re living through a giant bubble for a whole range of assets (houses, equities, crypto…), one that is fuelled by rock-bottom interest rates, extreme fiscal largesse and a large dose of FOMO. Alternatively, maybe something else is going on: compounding innovation, exponential progress and the law of accelerating returns.

- I’ve just finished listening to the audiobook version of Dambisa Moyo’s How Boards Work. Moyo opens by arguing that businesses ‘are reckoning with a period of shocks, tremendous uncertainty, and heightened complexity that is testing whether corporations, and indeed capitalism itself, will survive’ and that ‘In all times, but especially in times of turmoil, corporate boards have a responsibility as custodians not just of a single organisation, but of our economic well-being as a whole. The prosperity of society relies on corporate boards succeeding.’ What follows is a combination of a basic introduction to what boards do, some reflections on the role of boards drawing on her own experience with those on which she has served over the past decade or so (spanning banking, consumer goods, technology, oil and gas, media and mining) and an argument that boards will have to adapt to what Moyo sees as ‘five critical issues no board should ignore’: the risk of a more siloed and protectionist world; massive changes in the investment landscape; new technological developments; the global war for talent; and short-termism.

- Finally, the Econtalk podcast with economist Michael Munger makes the case for free markets. Market sceptics could probably argue that host Russ Roberts gives Munger an overly-gentle ride here (not surprising given they both agree on the topic) but at a time when much of the zeitgeist is focussed on issues of market failure, this provides a reminder of what markets offer.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content