A very quiet week on the Australian data front means a much shorter weekly update this time after several bumper issues. Following seven consecutive weekly falls, consumer confidence has increased although it remains very subdued.

The RBA minutes show the central bank remains prepared to adjust policy in the future but is unwilling to do so for now, despite forecasting that it will miss both its explicit inflation and implicit unemployment targets. Private sector forecasters have turned somewhat more pessimistic about growth outcomes this year and next. Australia saw an unprecedented fall in visitors in 2019-20, bringing a decade-long trend of rising arrivals to an abrupt end.

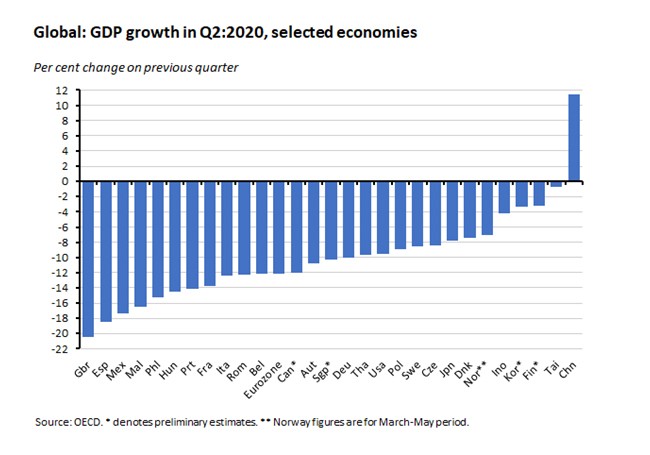

Second quarter GDP numbers from around the globe show the UK suffering its deepest fall in output on record, Southeast Asia experiencing Asian Financial Crisis-like declines in quarterly activity, and offer mixed evidence on the economic payoffs from the ‘Swedish model’ of pandemic response.

This week’s readings include Australia’s economic prospects in a post-COVID world, rethinking the minimum wage, reshaping China’s state capitalism, the search for new ‘alternative’ economic indicators, the impact of the pandemic on trade costs, the pandemic depression and the economics of skyscrapers.

Finally, for any readers that have access, just to note that I’m taking part in a CEDA online webinar on the economic outlook next week.

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

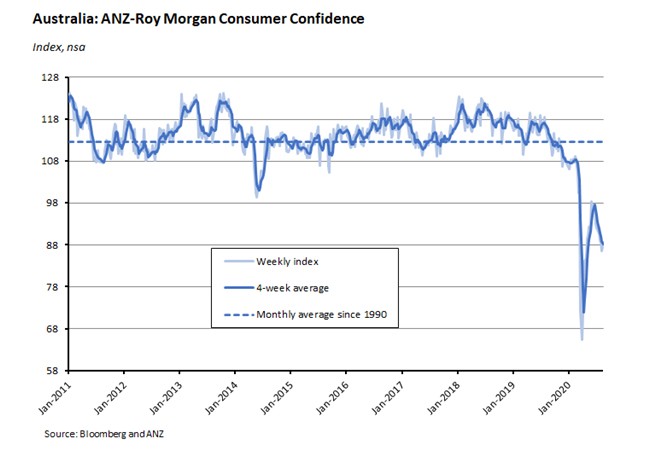

The ANZ-Roy Morgan weekly consumer confidence index rose 2.4 per cent to an index value of 88.6.

With the exception of ‘current finances’ all of the subindices rose last week, with the biggest increases coming in the ‘current economic conditions’ subindex, which jumped 10.6 per cent, partially unwinding a cumulative fall of 30 per cent over the previous eight weeks.

Consumer confidence increased in Melbourne by 5.1 points to 86.1, although that city still has the lowest index reading of all the major capital cities, behind Sydney (88.4), Brisbane (88.9), Adelaide (90.1) and Perth (97.3).

Why it matters:

The increase in the index for 15/16 August brought to an end a run of seven consecutive weeks of falling confidence, with the Melbourne result in particular likely reflecting the significant downturn in the number of new cases of COVID-19 recorded since the peak of 5 August. That still leaves the index well down on the same period last year and far below the long-term average, however, indicating that while the slide may have stopped last week, consumer sentiment remains very fragile.

What happened:

The RBA published the minutes from the 4 August Monetary Policy Meeting of the RBA Board.

Board members discussed the three scenarios that underpinned the August Statement on Monetary Policy (SOMP) and noted that ‘significant spare capacity, high unemployment and slow wages growth would contribute to a prolonged period of low inflation. The possibility that supply disruptions could lessen disinflationary pressures was considered, but weakness in demand was expected to be the dominant factor affecting inflation outcomes in the period ahead.’ As a result, underlying inflation ‘was forecast to remain below two per cent over the forecast period in each of the scenarios considered.’ In the baseline scenario, it was forecast to fall to a ‘trough’ of around one per cent late in 2021 and to only have risen to around 1.5 per cent by the end of 2022. In the upside scenario, inflation might reach 1.75 per cent by the end of next year, and in the downside scenario inflation was expected to trough at around 0.5 per cent and increase only a little by the end of 2022.

Despite this outlook, members also ‘reaffirmed that there was no need to adjust the package of measures in Australia in the current environment. Members agreed, however, to continue to assess the evolving situation in Australia and did not rule out adjusting the current package if circumstances warranted.’

Why it matters:

Since the 4 August RBA meeting, we’ve seen the release of the latest SOMP plus had the opportunity to cast our eyes over Governor Lowe’s testimony to the House Standing Committee on Economics (see weekly readings, below). As a result, the minutes didn’t bring us much in the way of new information.

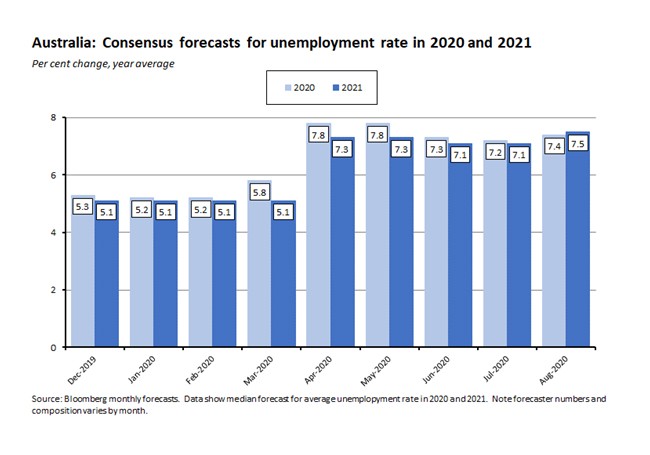

They did, however, once again leave us with the ongoing puzzle of a central bank that simultaneously judges that it has no chance of hitting its inflation target over the next couple of years while at the same time seeing no need to adjust its current policy settings. Likewise, the RBA thinks the unemployment rate will remain well above its estimate of an equilibrium rate of around 4.5 per cent, with the unemployment rate forecast to be seven per cent by the December quarter of 2022 in the SOMP’s baseline scenario. Private sector forecasters agree that inflation and unemployment readings will continue to disappoint (see below).

So, how should we view that declaration of inaction? One interpretation is that the RBA is either out of ammunition or thinks it is. But we know that is not quite the case, as the governor has noted on several occasions that there is more that the central bank can do. Another interpretation – and one that fits more closely with recent RBA communications – is that under current circumstances it thinks that fiscal policy is the superior tool for boosting the economy, and therefore that Martin Place accepts that Canberra now has the lead role. That argument has a lot going for it, since fiscal policy does have much greater traction than monetary policy right now. Still, it doesn’t necessarily follow that letting fiscal policy take the lead has to mean monetary policy should make no further contribution, particularly if the RBA is convinced that inflation will be too low and joblessness too high for at least the next couple of years.

What happened:

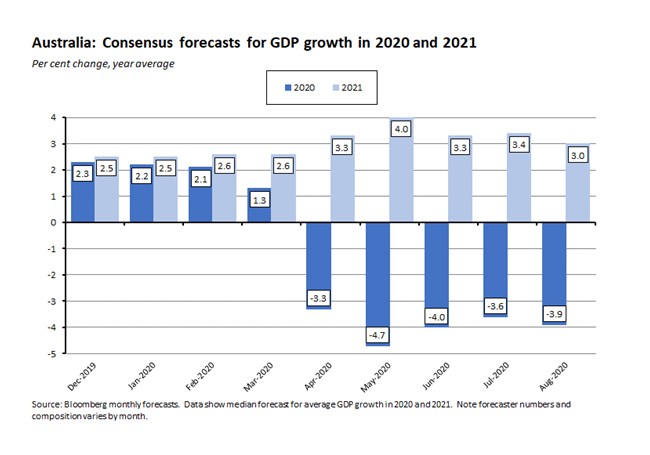

Bloomberg released the results of its latest monthly survey of economists, this one covering 39 economists polled between 13 and 18 August. This month, the consensus (median) forecast for economic growth in 2020 fell to a contraction of 3.9 per cent, down from a 3.6 per cent contraction forecast in July. Real GDP growth next year is now expected to be three per cent, down from a median forecast of 3.4 per cent in July. And the median projection for growth in 2022 has edged down from 3.3 per cent in July to 3.2 per cent in this month’s survey.

Forecasts for unemployment have been nudged up, too. Last month, the median forecast was for an unemployment rate of 7.2 per cent this year, 7.1 per cent next year and 6.1 per cent in 2022. As of August, the new median forecasts are 7.4 per cent, 7.5 per cent and 6.7 per cent, respectively.

Finally, private sector expectations for inflation are little changed from last month. The annual rate of increase in the CPI is now seen as averaging 0.6 per cent this year vs a prediction of 0.7 per cent in July, but the forecasts for 2021 (1.6 per cent) and 2022 (1.9 per cent) are unchanged.

Why it matters:

Surveys from the previous two months had shown private sector forecasters becoming a little more optimistic about the growth outlook, particularly for the coming year. August’s results indicate that recent developments in Victoria and to a lesser extent New South Wales have served to dampen that optimism, with this year’s downturn now expected to be deeper, and next year’s upturn shallower, than before.

What happened:

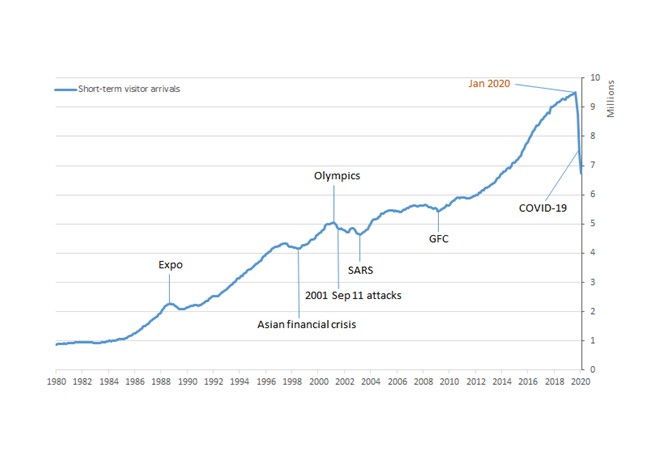

Last Friday, the ABS reported that Australia had suffered an unprecedented fall in the number of visitor arrivals in 2019-20. According to the Bureau, Australia received 6.7 million overseas visitor arrivals, down 27.9 per cent on the previous year and the lowest total recorded since 2013-14.

New Zealand was the largest source country, with over one million visitors nationally, and was also the largest for source market for Queensland and Tasmania. China was the largest source for New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and the ACT, and with almost 900,000 visitors nationally was Australia’s second largest source of international arrivals overall. Over the past decade, arrivals from China have grown by about 130 per cent. The UK was the largest source of arrivals for Western Australia while the United States played that role for the NT.

There were also 8.6 million resident returns from overseas in 2019-20, down almost 24 per cent on the previous year and the lowest number recorded since 2012-13. New Zealand was once again the leading destination country for Australians travelling overseas, with 1.1 million trips, and was also the most important destination for New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Tasmania and the ACT. Indonesia was the second most popular destination nationally and the leading destination for South Australia, Western Australia and the NT.

The ABS also noted a dramatic decline in international student arrivals: in June 2020 there was a decrease of 45,980 students (nearly 100 per cent) compared to June 2019, with Australia receiving less than 60 arrivals travelling on an international student visa.

Why it matters:

The impact of COVID-19 and the associated restrictions on international travel has produced a dramatic break in the trend of short-term visitor arrivals to Australia. The decade pre-pandemic had seen a continuous rise in the number of visitors, with a record 9.5 million visitors to Australia in the year ending January 2020.

Source: ABS

Provisional estimates for July, published earlier this week, show international arrivals and departures continued to more or less flatline into the first month of 2020-21.

. . . and what I’ve been following in the global economy

What happened:

Two weeks ago, we looked at the first tranche of second quarter GDP results from across the global economy. Since then, we’ve had several more releases.

Notable developments include:

- The UK suffered a severe 20.4 per cent quarterly decline in GDP, marking the deepest recession since the current series began in 1955. That’s a worse outcome than any other G7 economy and any of its major EU neighbours.

- Some Southeast Asian economies have seen falls in output reminiscent of those seen during the Asian Financial Crisis, with double-digit quarterly contractions in Malaysia and the Philippines and an almost double-digit decline in Thailand.

- Japan’s GDP fell by a record 7.8 per cent over the June quarter. That was a better performance than the UK, EU or United States, but not as good as other Northeast Asian economies such as Korea and Taiwan, which saw much shallower declines.

- In Scandinavia, quarterly falls in GDP in Denmark (down 7.4 per cent) and Finland (down 3.2 per cent) came in below Sweden’s 8.6 per cent contraction.

Why it matters:

The ongoing release of second quarter GDP numbers continues to fill in the picture of the blow COVID-19 inflicted on the world economy earlier this year. The data also tell some interesting stories about the differential impact of COVID-19 and the associated public health measures.

In the case of the UK, for example, the story is a particularly grim one, with the country suffering from one the deepest quarterly falls in output of any major economy. That perhaps reflects the combination of being slower to enter lockdown than other EU countries but then imposing a stricter lockdown that lasted for longer than many of its peers. A relatively high share of services in the economy is also likely to have been a factor.

In East Asia there is a marked difference between the relative hit suffered by Northeast and Southeast Asian economies, although in terms of the size of the quarterly fall in output, Indonesia has fared better than better than many of its ASEAN peers.

And the Scandinavian story is also an interesting one. Initially, Sweden’s quarterly GDP result of a contraction of less than nine per cent in contrast to much larger quarterly declines in some other EU economies was cited as potential evidence that Sweden’s more relaxed approach to lockdown had paid off in terms of less economic damage. Now, however, news of smaller output declines in Denmark and Finland (and likely Norway, where although full Q2 data are not available, data for the March – May period show a 7.1 per cent contraction), which all initially imposed more restrictive health measures than their neighbour, suggest that the narrative around the relationship between lockdowns and economic contractions is not quite that straightforward.

What I’ve been reading

Last Friday, RBA Governor Philip Lowe testified to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics. His opening statement is here and the Hansard transcript can be found here. The statement covers much of the same ground as the recent August Statement on Monetary Policy and the Governor’s 21 July Speech, both of which were analysed in depth in previous editions of the Weekly, although its worth noting that the opening statement to the Committee did again flag the possibility of further adjustments to the RBA’s policy stance, with the Governor noting that the RBA has ‘not ruled out a separate bond buying program, or other adjustments to the mid-March package. But for the time being, the Board's view is that the best course of action is to continue with the current package.’ The transcript covers a range of interesting issues, including the governor’s views on the balance between federal and state fiscal support, the trade-offs involved in state border closures, the case for extending insolvency relief measures, options for boosting Australian growth, the case for and against negative interest rates, and the RBA’s 1990s gold sales. To take just one example, according to the governor, we shouldn’t worry too much about what the rating agencies might think about rising public debt, since ‘creating jobs for people is much more important than preserving the credit ratings.’

John Edwards assesses the costs of COVID-19 and what they mean for Australia’s economic prospects in a ‘wounded world’. Edwards is - relatively - sanguine about the implications.

Ross Garnaut in the AFR on the case for a sharp break with pre-COVID policies and politics here in Australia.

This Roy Morgan report summarises the economic story of COVID-19 and Australia so far with a series of charts and indicators.

The NSW Productivity Commissioner has released a new Green Paper. See this op ed for a summary of two of the ideas proposed here.

The Economist magazine continues its new series on areas of economics where the profession is undergoing a rethink. This time the topic is the minimum wage, where views have become much more nuanced.

Also from the Economist: a briefing on how Xi Jinping is seeking to remake China’s version of state capitalism. ‘The idea is for state-owned companies to get more market discipline and private enterprises to get more party discipline.’

From the ‘champagne index’ to the ‘canned meat index’: the search for new alternative economic indicators post-pandemic.

The WTO has published a new report on the impact of the pandemic on global trade costs. Travel and transport costs can account for as much as a third of trade costs depending on the sector and have been significantly impacted by travel restrictions and border closures.

This Rolling Stone essay on the Unravelling of America has been receiving a fair bit of linkage over the past couple of weeks.

This one is a bit dated now, but still worth a read: Bloomberg’s Daniel Moss on Bank Indonesia’s radical monetary policy experiment. See also here.

The economics of skyscrapers: ‘If the history of height is any guide, the future direction for their economics is only upwards.’

An FT Big Read on presidential candidate Joe Biden’s plans for a ‘root-and-branch overhaul’ of the US energy sector.

Carmen and Vincent Reinhart on the pandemic depression and the need to avoid ‘confusing a rebound for a recovery’.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content