There will be jobs, plenty of jobs, just not as we know them — and this will require new work compact, reports Phil Ruthven FAICD.

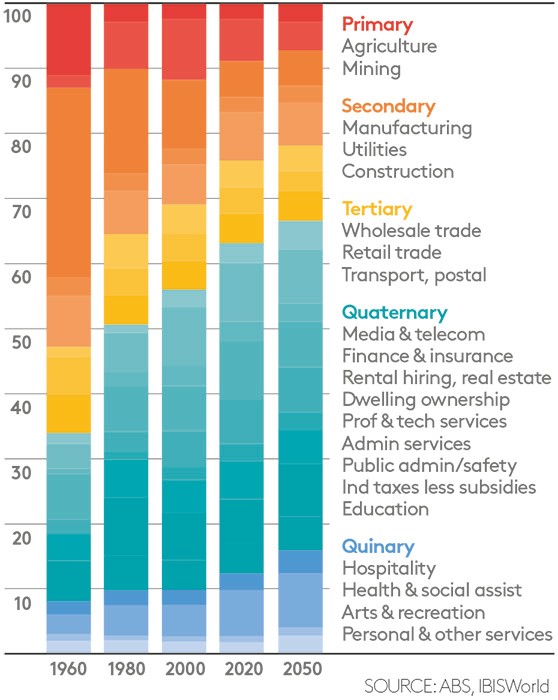

The nature of work is changing. The hours of work keep falling each year and the nation won’t run out of jobs. It won’t run out of workers through ageing and robots won’t create high unemployment. Employment is moving towards a reward for outputs, not inputs (hours) — altering industrial relations. And old industries are being replaced with new industries, mostly service industries, often with higher wages.

Where the jobs are

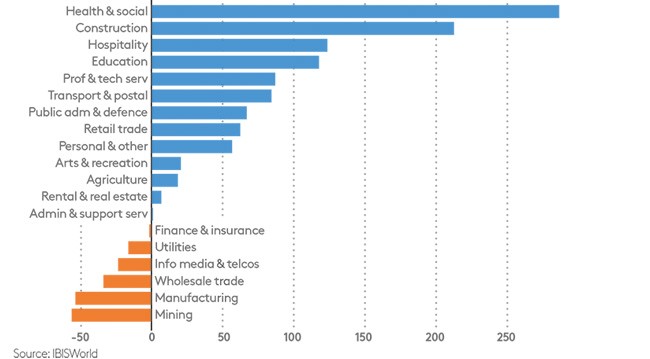

In the five years to September 2017, we created six times more jobs (1.2 million) than we lost (184,200). Some 53,000 manufacturing jobs disappeared, but we created over 286,000 positions in the health services industry — paying about eight per cent more than manufacturing jobs.

Four out of every five new jobs are created in the service sector, as in all advanced economies. While mining jobs declined, the industry continues to produce nearly half of our exports directly or indirectly (via processed minerals).

Over the same five-year period, more than 204,000 new jobs were created in the nation’s three lowest-paid industries — hospitality, retail and agriculture.

Outsourcing of household activities has created a quarter of today’s 12.4 million jobs.

Ageing workforce

We are now utilising more of Australia’s ageing population, not less. In 2017, we employed 50 per cent of the total population, with an average age of 40. In 1965, at the end of the Industrial Age, we employed only 41 per cent of the population (average age 31). Compare this to 1901, when we couldn’t even employ 40 per cent because the population’s average age was only 22.

Work hours

Today, the average male will work 28 hours or less per week for 50 to 60 years and still have a decade or more of retirement, with the early and later years of working life being part-time.

While we think we now work a much longer week, the nominal hours are diluted by the two months that we don’t work at all each year (four weeks’ annual leave, two weeks of public holidays, two weeks of sick leave and sometimes long-service leave). The lifetime average hours per week must also take into account the part-time hours at the beginning and the end of our working lives.

Robot workforce

Artificial intelligence (AI) devices have been around for a long time, aiding workers and citizens — sometimes displacing them into other jobs, but not replacing them as workers in the labour force and community. The advent of tractors in the 1930s, and then chemical fertilisers after World War II, displaced more jobs in agriculture (15 per cent of the workforce) than goods-producing robots do today (three per cent).

AI is threatening a number of professional, technical and educational jobs where productivity has been absent for decades. In the US, for example, online legal services are proving cheaper and more accurate — and growing at more than twice the rate of traditional law practices.

The nature of work compacts

The most profound change in our working lives will be our work arrangements, or compacts. We are moving towards a b2b compact between businesses and workers, on individual or group contract bases. Unions — already down to 14.3 per cent of the workforce — will be replaced by professional advisers for work contracts (similar to mortgage brokers and financial planners). Millennials now account for 37 per cent of the Australian workforce and are seeking more liberty, flexibility and rewards for outputs.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content