Early February delivered a series of snapshots on how the RBA’s views on the economy have changed since the summer break, painting a picture of a central bank which, while still quite optimistic about the outlook, was rather less confident in its optimism than it had been previously.

For their part, financial markets are increasingly confident that the next move in the cash rate will be down, not up.

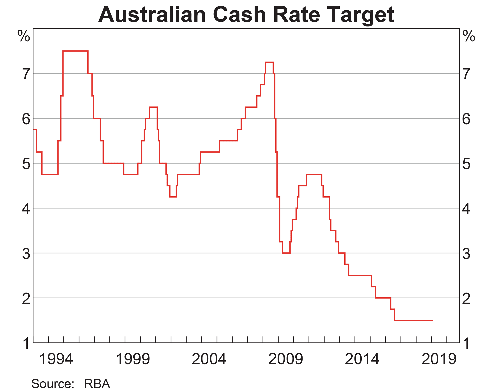

First up, we had the 5 February meeting of the RBA Board at which, to nobody’s surprise, the Bank decided to leave the cash rate unchanged at 1.5 per cent. That marked a record 27 consecutive meetings with no change since the RBA cut the cash rate by 25bp back in August 2016. (The last time the RBA raised rates – by 25bp – was November 2010.)

Source: RBA Chart Pack, February 2019

Next, Governor Lowe delivered his address to the National Press Club of Australia the following day. After a suitable disclaimer about the uncertainties involved (‘we don’t have a crystal ball’), Lowe gave us a brief tour, first of the global economy (‘while some of the downside risks have increased, the central scenario for the world economy still looks to be supportive of growth in Australia’) and then of the domestic outlook (‘the downside risks have increased, although we still expect the Australian economy to grow at a reasonable pace’). Commentators highlighted the retreat from the RBA’s previous position (as expressed for example in the minutes from the 4 December 2018 meeting) that ‘the next move in the cash rate was more likely to be an increase than a decrease’ to Lowe’s now somewhat more cautious assessment: ‘Over the past year, the next-move-is-up scenarios were more likely than the next-move-is-down scenarios. Today, the probabilities appear more evenly balanced.’ Overall though, the governor continued to signal he saw no strong case for a change in either direction.

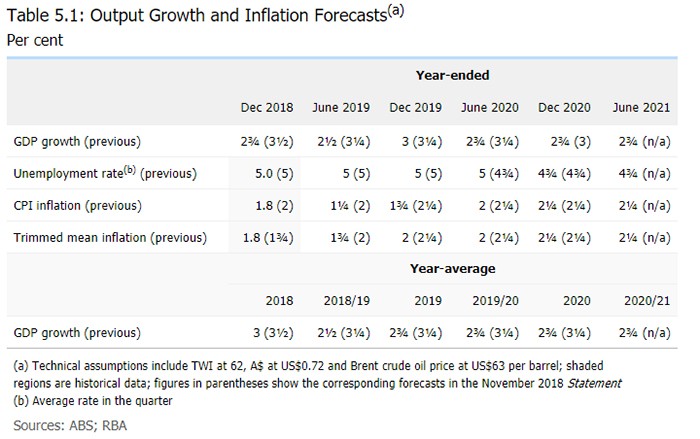

And finally, at the end of the week the RBA released the February Statement on Monetary Policy, which provided a great deal more context for that shift to a more cautious stance, along with a set of downwardly-revised growth and inflation forecasts.

Detail

Despite downward revisions to the outlook for growth in consumption and residential construction, the new RBA forecasts included in February’s Statement still tell a relatively optimistic story. They assume that after growth of 2.75 per cent this year, a rise in business investment, ongoing support from public spending and an increase in resource exports will together be enough to deliver real GDP growth of around three per cent over the course of next year and a little below that in 2020. That in turn is expected to translate into a modest decline in the unemployment rate, which is now predicted to drop to 4.75 per cent by the end of 2020, and this somewhat tighter labour market is associated with an anticipated uptick in wage growth. Headline and underlying inflation are both projected to show only a gradual increase.

Source: RBA Statement on Monetary Policy February 2019

Globally, key risks to this story include the future trajectory of Chinese growth, continued trade tensions, and the state of global financial conditions.

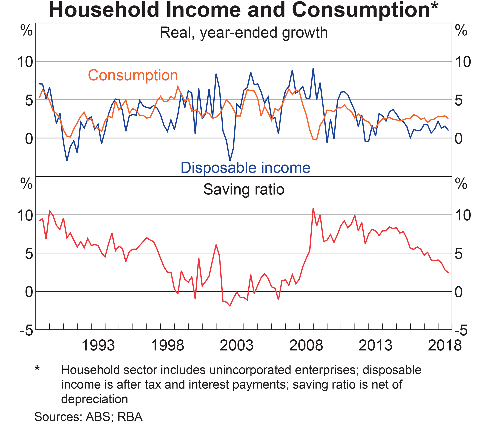

Closer to home, critical vulnerabilities relate to the nexus between consumer spending, wage growth and the housing market. In particular, the RBA is still hoping that a tighter labour market will eventually trigger faster wage growth and hence provide more support for household consumption, which alone accounts for more than half of GDP. The challenge here is that in recent years wage growth has repeatedly disappointed those hoping to see a sustained pickup, and while Australian consumers have proved willing to sustain their spending in the face of soft income growth by digging into their savings, the current drop in house prices and the consequent hit to household wealth – along with high levels of household debt – suggest that they will be increasingly reluctant to continue to do so. And a markedly softer consumption story, should it eventuate, would of course have implications for business confidence and investment.

Source: RBA Chart Pack, February 2019

So, key takeaways from the RBA’s musings and the subsequent market response are:

- if the RBA’s forecasts turn out to be on the money, the central outlook for the economy is still reasonably positive, if a little less so than last year’s rosier prognosis;

- the risks are that things will turn out to be a bit softer than the RBA hopes; and

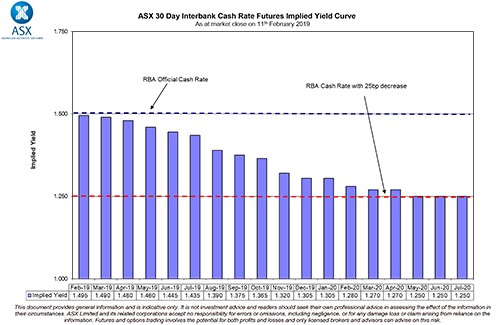

- with this risk profile in mind, markets – and a growing number of market economists – are now betting that the direction of the next cash rate change will be down. The implied yield curve on ASX 30 day interbank cash future rates as of 11 February indicates that the market then expected the RBA to cut rates by 25bp by early next year.

Source: ASX RBA rate indicator

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content