New CBA data suggests private sector services activity in Australia rebounded this month. Total job vacancies suffered an unprecedented fall in the three months to May. Preliminary data suggest retail sales enjoyed record monthly growth in May. Mobility and reservations data also support the story of an increase in activity. Consensus forecasts for Australian growth in 2020 have been revised upward this month (although they are still deep in negative territory).

The ABS has released new insights on how Australian businesses are adjusting their operations in reaction to COVID-19. The IMF has slashed its forecasts for the global economy this year, although it too is now more optimistic on Australia.

This week’s readings include a debate over Australia’s approach to China, our policy framework for foreign investment, the new world disorder, Martin Wolf’s economics reading recommendations and contemplating radical uncertainty.

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

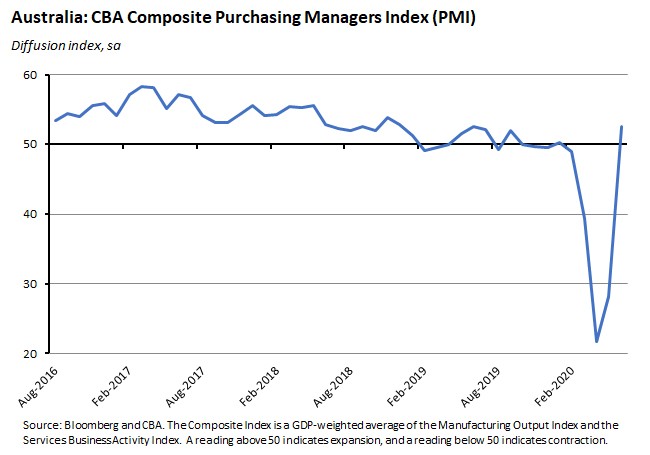

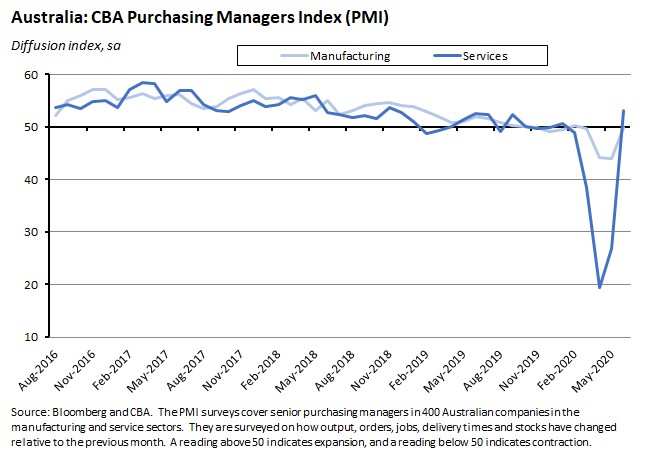

The latest CBA ‘flash’ estimate of the composite Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) show private sector activity growing in June as the index rebounded from 28.1 in May to a preliminary estimate of 52.1 for this month (flash indices give an advanced read on the final PMI readings and are based around 85 per cent of final survey responses).

That rise in the composite index was driven by a recovery in activity in services, with the flash reading increasing from 26.9 in May to 53.2 in June. In contrast, manufacturing remained in negative territory, albeit still up from 44 to 49.8, indicating a more modest pace of contraction in the sector than in May.

Why it matters:

The shift in the composite PMI back to positive territory and the big jump in the services PMI indicate a pickup in activity in June, in line with the gradual easing of public health restrictions. This was also the first time that both the composite and services PMI have been in expansionary territory since January (although recall that the PMI measures the change in business activity on the previous month, so while activity has lifted in June relative to May, that still leaves the overall level of activity below its pre-CVC level).

What happened:

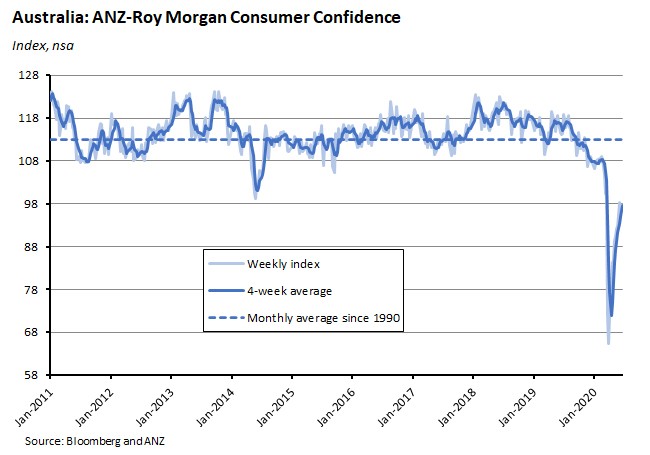

The ANZ-Roy Morgan weekly consumer confidence index was unchanged this week with an index value of 97.5.

Current financial and economic conditions remain subdued: 23 per cent (down one per centage point from last week) of Australians say their families are ‘better off’ financially than this time last year and 36 per cent (up one per centage point) say their families are ‘worse off’. Similarly, only ten per cent (up one per centage point from last week) expect ‘good times’ for the Australian economy over the next 12 months while 40 per cent (up two per centage points), expect ‘bad times’. Future financial and economic conditions return stronger readings, but while future economic conditions improved slightly relative to last week’s reading, the future financial conditions result has weakened (with a three per centage point drop in the share of Australians expecting their family to be ‘better off’ financially this time next year and a one per cent increase in the share expecting to be ‘worse off’.

Why it matters:

We noted last week that there were signs that consumer confidence had levelled off after bouncing back from its March and April lows, with improved sentiment regarding the medium term offset by the reality of tough current conditions. Both the flat headline reading and the details from the component indices are consistent with that story.

What happened:

According to the ABS, preliminary estimates for Australian international merchandise trade in May show the value of exports fell four per cent over the month and 13 per cent over the year while the value of imports slumped nine per cent in monthly terms and 18 per cent in annual terms. These big drop in import values were mostly due to a fall in imports of road vehicles and petroleum.

Why it matters:

The preliminary data provide some interesting insights into the way COVID-19 is influencing Australia’s trade in goods. In terms of exports, the May numbers show substantial declines in exports of non-monetary gold, coal and gas. The drop in coal and gas exports reflects softer demand from key trading partners. Exports of iron ore remained strong last month, however, due to both continued Chinese demand and COVID-19 related supply disruptions in Brazil. Exports of iron ore now account for about a quarter of all Australian export values.

On the import side of the trade accounts, purchases of road vehicles have now fallen to their lowest level since April 2011 with particularly large drops in imports of passenger vehicles and four-wheel drives. At the same time, petroleum imports have dropped to their lowest level since February 2005, with imports of crude petroleum and aircraft fuel driven down by the decline in demand due to COVID-19 restrictions and lower oil prices.

What happened:

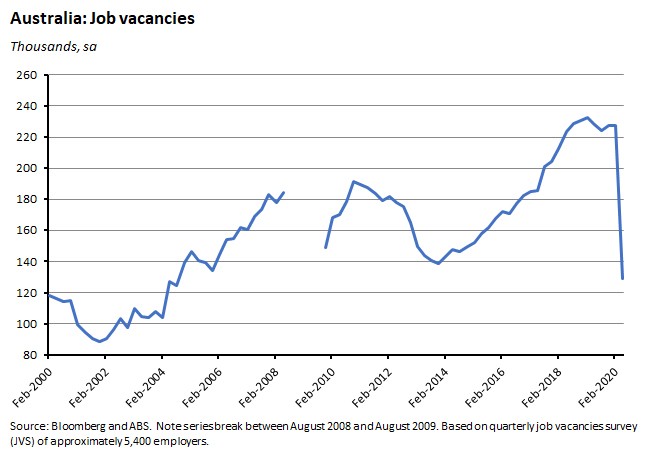

Total job vacancies in the three months to May 2020 were 129,100, a decrease of 43.2 per cent or 98,200 vacancies from February 2020. According to the ABS, the number of private sector job vacancies fell 45 per cent while the number of job vacancies in the public sector dropped by 28.9 per cent.

Vacancies in arts and recreation services fell 95 per cent (in original terms), vacancies in rental, hiring and real estate fell 68 per cent and vacancies in accommodation and food services fell 66 per cent.

The ABS said 93 per cent of businesses reported no vacancies at all in May 2020, up from 88 per cent in May 2019. In arts and recreation services close to 100 per cent of businesses reported no vacancies as did 98 per cent of businesses in accommodation and food services.

Why it matters:

The ABS noted that the 43 per cent drop in vacancies was ‘unprecedented in the history of the series, and reflect the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated restrictions on people and businesses, most of which were still in effect on Friday 15 May 2020 (the survey reference date)’. The previous largest quarterly declines in the series came in the early 1990s recession (a 26.7 per cent fall in November 1990) and in the early 1980s recession (an 18.6 per cent decline in May 1982), so the present decline is far larger. Unsurprisingly, those sectors which experienced the largest drops in vacancies tended to be those services industries most exposed to social distancing restrictions.

What happened:

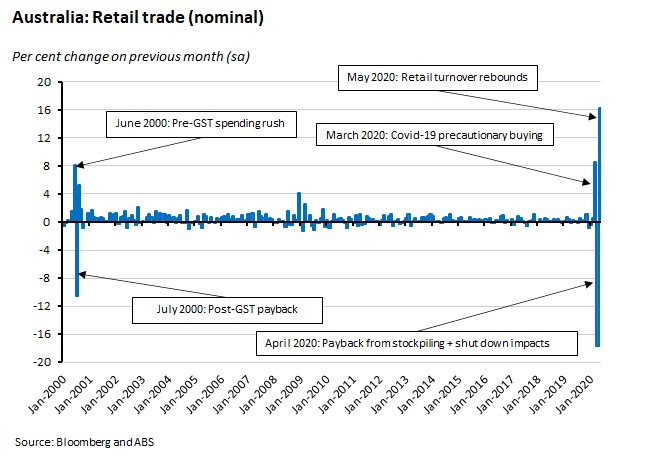

Last Friday, the ABS published preliminary data on May retail turnover (based on early data provided by businesses that make-up approximately 80 per cent of total retail turnover). Retail turnover rose 16.3 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) to be up 5.3 per cent over the year.

The ABS reported large increases in turnover in clothing, footwear and personal accessory retailing and in cafes, restaurants and takeaway food services, as restrictions eased throughout the month. But while the rise in the former exceeded 100 per cent over the month, turnover remained more than 20 per cent down on May 2019. Similarly, while turnover in cafes, restaurants and takeaway food services rose around 30 per cent relative to April this year, it was still 30 per cent below the level of May 2019.

Turnover also increased across in the household goods retailing industry and in food retailing, and in the case of the latter the ABS noted that this was consistent with consumers purchasing additional food and beverage for home consumption.

Why it matters:

May’s preliminary result marks the largest seasonally adjusted month-on-month rise in the 38-year history of the series and is dramatic payback for April’s record monthly fall of 17.7 per cent. The bounce in spending also matches weekly credit and debit card data which have shown a recovery in spending across May and into June, along with a gradual recovery in in-store shopping and a pickup in spending on services. Surveys of retail spending intentions have also strengthened.

What happened:

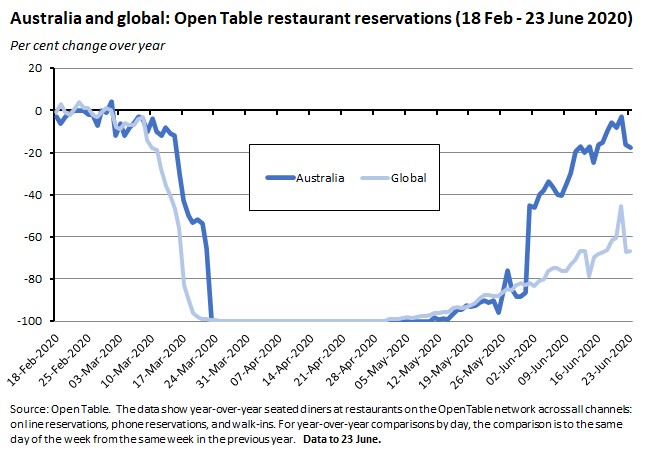

Several indicators suggest that Australia’s economy is continuing to emerge from the deep freeze that was imposed earlier this year. For example, restaurant bookings have increased markedly since mid-May (although they have fallen back somewhat in recent days):

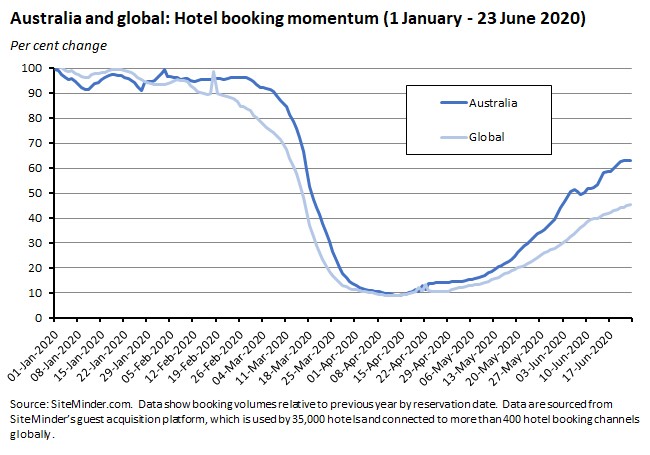

Similarly, hotel bookings have also been showing signs of recovery:

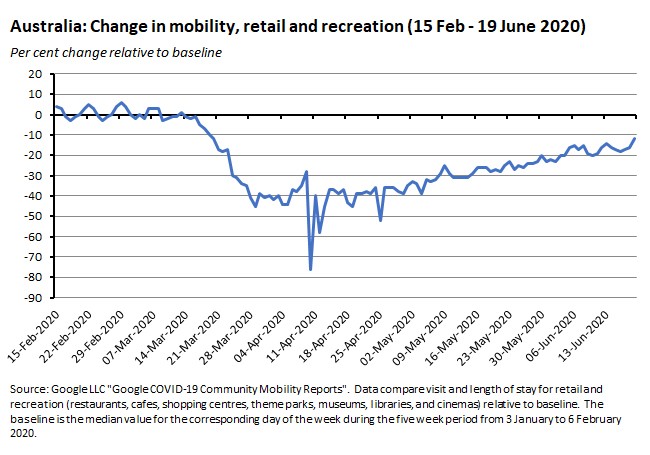

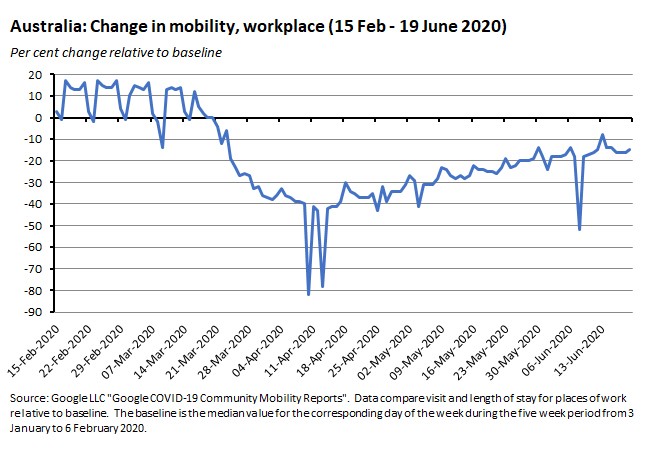

More generally, mobility indicators are showing increased traffic in retail and recreation zones:

As well as increased visits to, and lengths of stay in, workplaces:

Why it matters:

As the economy emerges from lockdown, mobility measures are one early indicator of returning economic activity more generally. Likewise, increases in restaurant and hotel reservations are consistent with the story of recovering consumption told by last Friday’s retail turnover numbers (see the previous story) as well as the rise in spending reported by the banks’ credit and debit card data.

What happened:

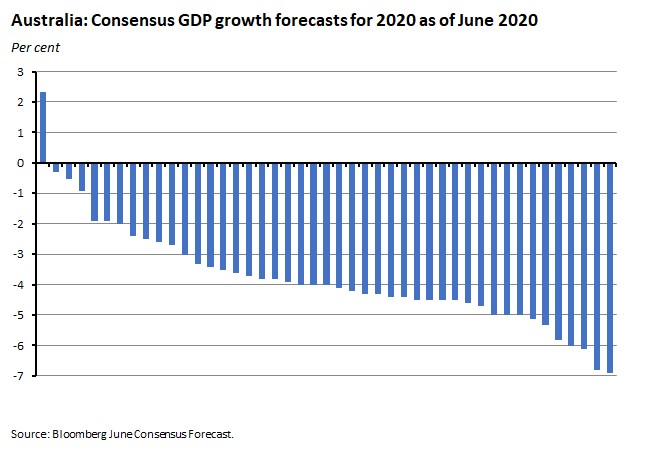

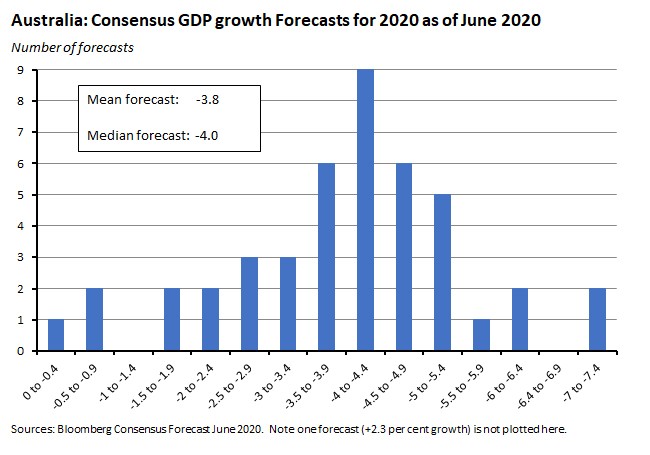

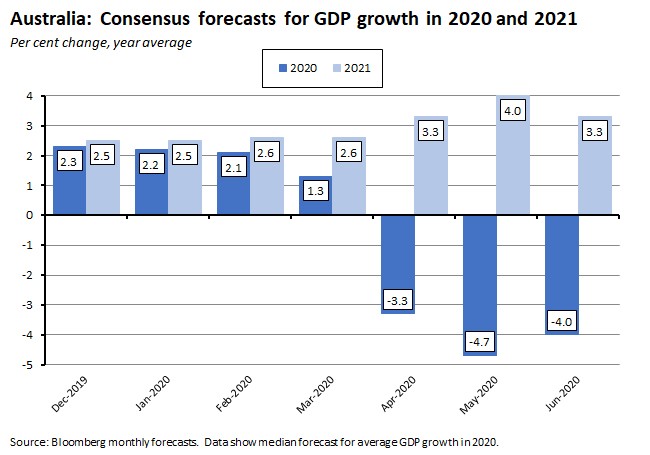

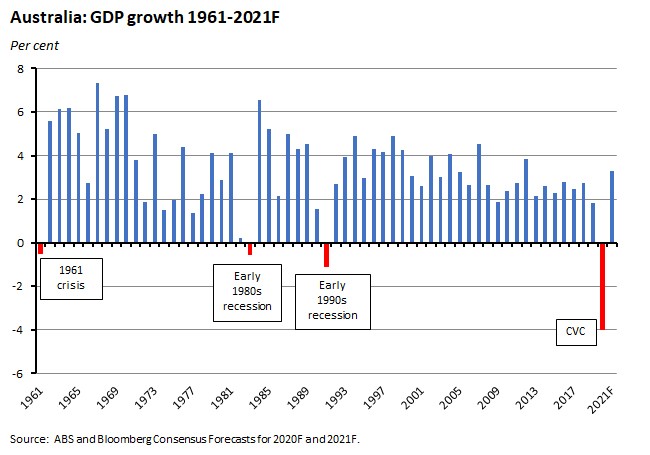

Bloomberg consensus forecasts for June show the median projection from 45 private sector economists is for Australia’s real GDP to shrink four per cent this year. The underlying individual forecasts range from one positive outlier which puts growth this year at plus 2.3 per cent to the most pessimistic forecast, which has the economy shrinking by almost seven per cent.

The mean forecast is for a 3.8 per cent contraction, while more than half of the reported projections range between falls of 3.5 per cent and 5.4 per cent.

Why it matters:

June’s median forecast for a fall of four per cent in real GDP this year represents an upgrade on May’s median forecast of a 4.7 per cent drop. That improvement in the outlook is consistent with the upturn in short-term activity indicators noted above as well as the earlier strengthening in those indicators that we highlighted last month. It’s also in line with the revised IMF forecast for Australia discussed below. The now-smaller expected contraction this year is also matched by a reduction in the median forecast for GDP growth for 2021, which has been pared back from four per cent in May to 3.3 per cent in the June forecast roundup (a smaller downturn this year implying a more modest snapback next year for most forecasters).

Finally, however, a cautionary note. At four per cent, the anticipated fall in GDP this year would still be – by far – the deepest recession in the post-war period.

Despite the upturn in the outlook that we’ve been seeing, last week’s grim labour market report and this week’s record-breaking fall in reported vacancies are both ugly reminders of the scale of the economic dislocation being suffered by the Australian economy and Australian workers.

What happened:

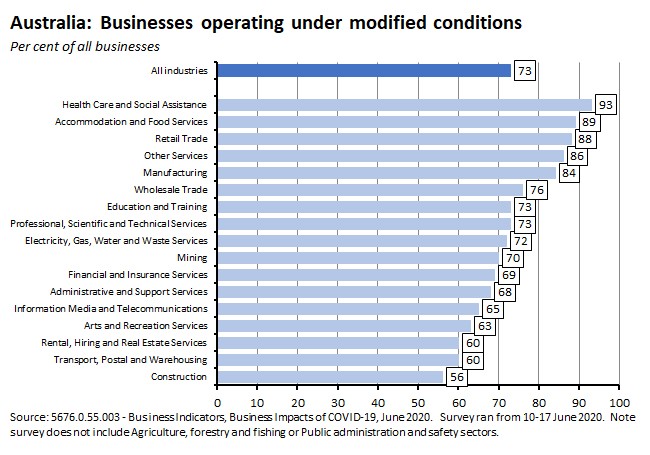

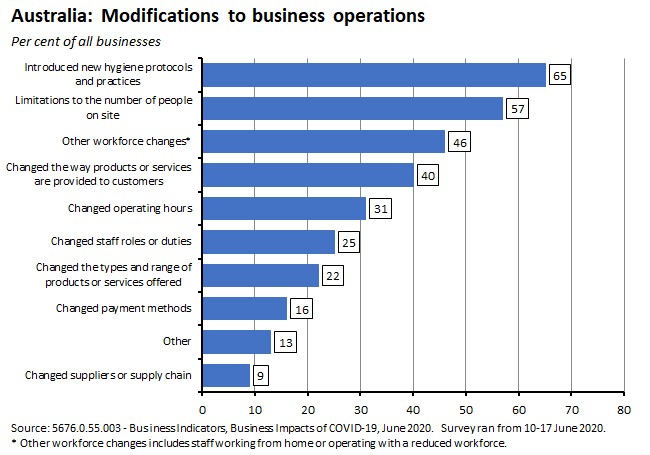

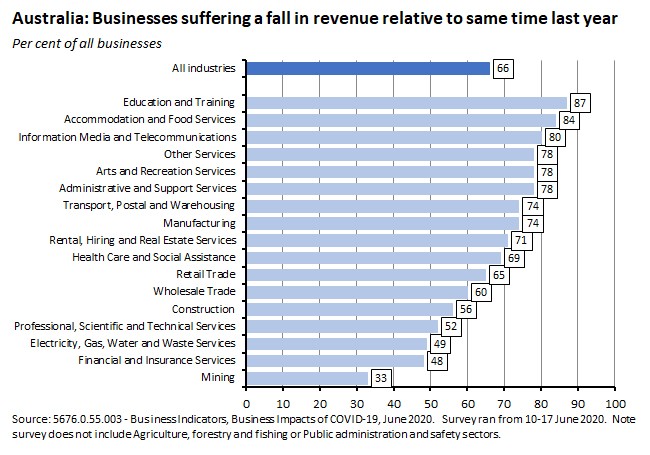

The ABS published the results from the Business Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, June 2020. This latest survey in the new ABS CVC-era series was conducted between 10 and 17 June with a sample size of 2,000 (and a response rate of 72 per cent). The questions covered: modifications to business operations; the subjects and sources of external advice sought by business; changes in business revenue compared to same time last year; and the length of time business operations could be supported by available cash on hand.

In the June survey, 73 per cent of all businesses reported that they were operating under modified conditions due to COVID-19, up slightly from the 70 per cent reporting the same in May. That share ranges from 93 per cent of all business in the health care and social assistance sector to 56 per cent of construction businesses.

The most common modifications introduced by businesses in response to the virus have been new hygiene protocols and practices (65 per cent of all businesses), limitations to the number of people on site (57 per cent) and changes to the workforce such as more working from home or a reduction in the size of the workforce (46 per cent).

Some 60 per cent of businesses reported seeking external advice in response to COVID-19, including obtaining information online or in print, or via paid or unpaid direct consultation with individuals or organisations external to the business. The most popular topics were the availability of government support measures and information on regulation and compliance.

Two thirds of all businesses reported that their revenue had decreased compared to the same time last year. Education and training services had the largest share of businesses reporting a fall in revenue while the mining sector was the least affected on this metric.

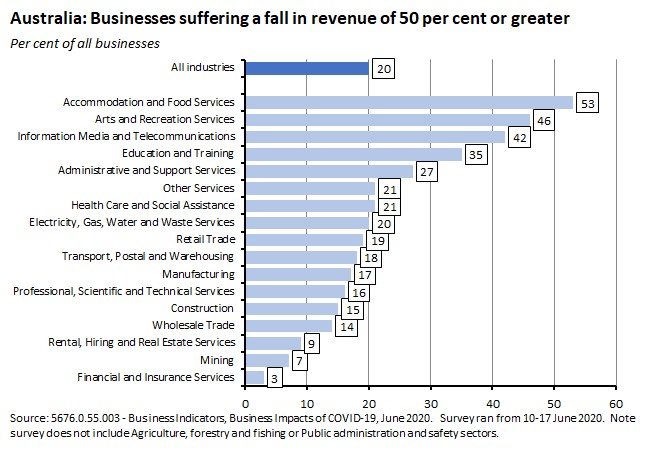

In terms of the scale of revenue loss, 20 per cent of all firms reported suffering a fall in revenue of 50 per cent or more relative to the same period last year. Again, there were substantial differences across sectors, with 53 per cent of businesses in the accommodation and food services sector, 46 per cent of those in arts and reaction services, and 42 per cent of those in information, media and telecommunications reporting losses on this scale relative to just seven per cent of mining businesses and three per cent of businesses in finance and insurance.

Finally, the ABS asked businesses to provide a rough estimate (that is, without consulting business records or reports) of the length of time that, under current conditions, operations could be supported by currently available cash on hand. While 36 per cent said they had enough cash to sustain operations for six months or more, 21 per cent said they had a buffer that would last between one and three months and eight per cent said they could only support operations for less than one month.

Why it matters:

These regular surveys of business response to COVID-19 by the ABS show both the extensive impact of COVID-19 on Australian business activity and operations overall but also the significant variance in that impact across different sectors of the economy.

. . . and what I’ve been following in the global economy

What happened:

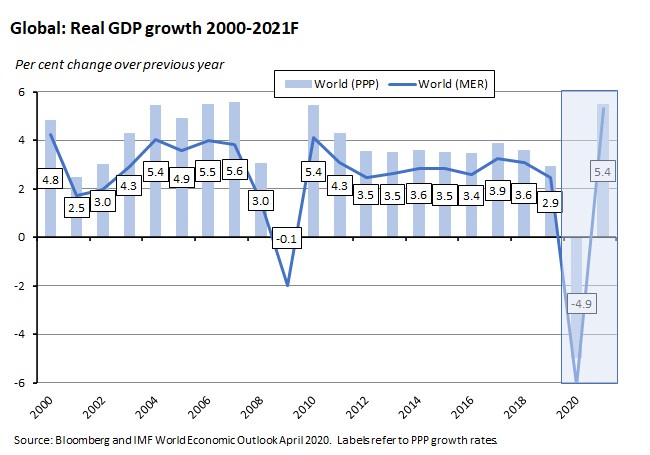

The IMF has updated its forecasts for the global economy. The Fund now thinks that the world economy will shrink by 4.9 per cent this year and grow by 5.4 per cent in 2021 under its baseline scenario (it also presents two alternative scenarios, one assuming a faster recovery in the second half of this year, the other a new COVID-19 outbreak in 2021).

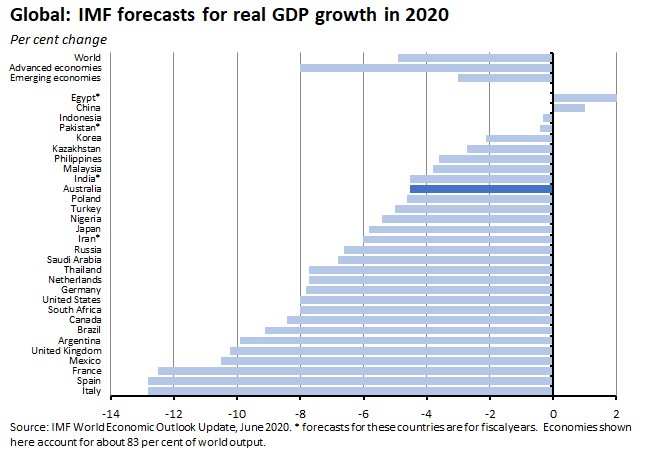

That steep decline in forecast activity for this year in the Fund’s baseline scenario is reflected in a range of dismal forecasts for most of the world’s major economies. Real GDP is now expected to decline at a double-digit rate in the UK, France, Spain, Italy and Mexico, by more than nine per cent in Brazil, by eight per cent in the United States and by 7.8 per cent Germany. Of the 30 economies for which the IMF presents individual forecasts in this update, only two – Egypt and China – are projected to see GDP expand in 2020.

Every region in the world economy is expected to go backwards this year. Back in April, the IMF had thought that the emerging and developing Asian would be a lone exception to what was otherwise a global contraction. No longer.

Why it matters:

These new IMF forecasts embody a series of major downgrades to the preceding April World Economic Outlook. That earlier forecast was already painting a grim picture for this year with growth in 2020 forecast to be minus three per cent – by far the worst outcome for the post-war period. Now, as well as expecting an even deeper recession this year, the Fund is also anticipating a shallower recovery in 2021.

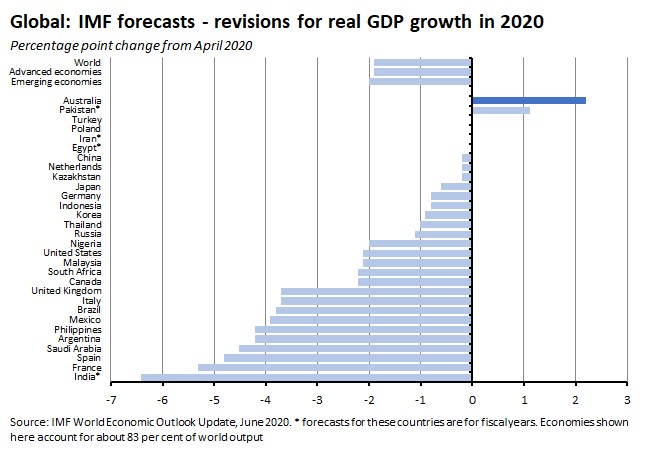

Of the 30 countries where the IMF has presented individual forecasts, there have been downward revisions to April’s growth projections for 24 of them. Moreover, many of those downgrades are dramatic ones, with a huge cut of more than six per centage points for Indian growth, a more than five per centage point downgrade for French growth and cuts of three per cent or more for the UK, Italy, Brazil, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, and Spain, for example. The Fund says these downgrades are a product of worse than expected first quarter GDP outcomes for many economies, partial indicators that are signalling an even more miserable second quarter for much of the world economy, and the expectation of significant additional economic scarring from these worse than anticipated outcomes.

Still, buried in all the bad news about the outlook for the global economy, there was some relatively good news for Australia. We were one of only two countries to see their growth outlook for this year upgraded (the other was Pakistan), with the IMF revising its forecast of a 6.8 per cent decline by 2.2 per centage points to a smaller decline of 4.6 per cent.

That upgrade is in line with the Bloomberg consensus forecasts discussed above, although note that the IMF’s new forecast is closer to the May 2020 Bloomberg median forecast of a 4.7 per cent decline than it is to the June median forecast for a four per cent contraction.

What I’ve been reading

The June 2020 Quarterly Statement from the Council of Financial Regulators.

A transcript (audio is also available) from the ANU Crawford Leadership Forum panel on the global economy and COVID-19, featuring Catherine Mann, Yiping Huang and the RBA’s Philip Lowe.

The ABS reported that average Australian household wealth decreased 2.3 per cent (down $9,982) to $428,585 per person in the March quarter of this year. That was the largest decrease since the September quarter 2011 and reflected falls in superannuation balances (down 8.2 per cent) and directly held equity holdings (down 5.3 per cent).

The Productivity Commission has released a new paper on foreign investment in Australia. The overall judgment is that ‘the design and vesting of responsibility with the Treasurer for administering the ‘national interest’ test works well. It gives flexibility to quickly adapt to new concerns…The ‘negative’ nature of the test (deciding whether proposals are contrary to the national interest) also limits the risk of rejecting projects that are in the national interest. These features should be retained.’ But the commission also suggests some improvements to the current policy framework.

The Lowy Interpreter has hosted an interesting dialogue on Australia’s relationship with China between Sam Roggeveen and Alan Dupont that touches on the case for, and costs of, diversification.

A new ANZ report on the Asian economy in a G-zero world.

The WSJ has a long essay on how COVID-19 will reshape world trade.

The New Yorker asks the same question about architecture, arguing that just as tuberculosis shaped modernism in the past (‘a desire to eradicate dark rooms and dusty corners where bacteria lurk’), so COVID-19 will shape future fashions in architecture.

Bloomberg Businessweek’s eight-point plan for office re-opening.

A BIS report on US dollar funding, co-authored by the RBA’s Christopher Kent.

Will (should?) COVID-19 lead to a convergence of US and European models of capitalism?

The Economist magazine has a special report on the new world disorder. It suggests three possible scenarios for the future: ‘bedlam’, ‘bumbling’ and ‘boldness’. It worries about the first, expects the second and hopes for the third.

An FT Big Read on the future of the newspaper industry.

Also from the FT, Martin Wolf’s recommendations for economics-related summer (in our hemisphere, winter) reading. Of his list, I’ve reached the final couple of chapters of the Kay and King book (see below) and have recently ordered the Lonergan and Blyth. Several of the others look very tempting, too.

One of the publications on Wolf’s list is The Deficit Myth by Stephanie Kelton. A listener to our Dismal Science podcast recommended this recording of a recent Australia Institute webinar with Kelton as an introduction to her ideas.

As already noted, I’m coming to the end of Mervyn King and John Kay’s Radical Uncertainty. Their book is a critique of the approach to quantifying uncertainty that is typically followed by economics and finance (and beyond), which they argue can mistakenly take techniques designed to work in small worlds with stationary data and seek to apply them inappropriately to our large, non-stationary world. They reckon that in practice, many of the most interesting and important questions we have to deal with relate to radical (or ‘Knightian’) uncertainty, which cannot be simply quantified in the way that many economic and financial models assume. It’s also possible to read their book as a kind of dialogue with / critique of Philip Tetlock and Dan Garner’s Superforecasting, with King and Kay taking several of the examples cited in the latter (think for example of the story of President Obama and the raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad) but reaching quite different conclusions as to the lesson(s) to be learned.

The book’s an interesting and wide-ranging read and covers a huge amount of ground. I’m very sympathetic to much of the argument. And overall, I’ve been enjoying it. All that said, at times it’s also been a bit hard going, mainly because it’s almost certainly too wide-ranging: the central argument sometimes all but disappears in the sheer amount of terrain that’s traversed here.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content