From nanosatellite technology to reusable rockets, Australia has a big opportunity to make its mark in space.

SpaceX strapped a red Tesla sports car to a rocket and sent it hurtling toward Mars in early 2018 — but its ultimate goal is to enable humans to live on other planets. Right now, the business founded by Elon Musk is having a bigger impact on this planet: launching reusable rockets at the rate of more than one a fortnight, it’s delivering small satellites into space far more cheaply than has been previously possible.

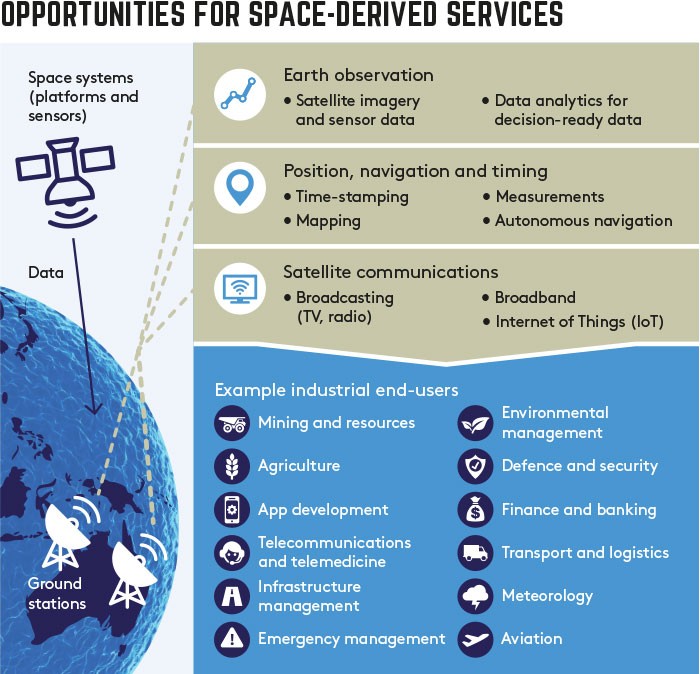

This capability from SpaceX and other commercial rocket launch businesses makes satellite communications affordable for applications across agriculture, mining, urban planning and utilities. Space-based technology makes possible the latest incarnations of online banking, mobile communication, global positioning systems, the internet, television, emergency communications and transport — as well as an array of military applications.

It’s creating a wave of space-focused investment and startups. Australia’s space industry currently generates revenues of $3–$4 billion per year and employs around 10,000 people in 388 companies and 56 education and research institutions. According to Dr Jason Held, founder and CEO of Saber Astronautics: “The opportunity is global — we are looking at tripling the number of satellites and the size of the space market. It’s a $420b market about to triple in 10 years. When you have a market tripling over 10 years, you would think moneyed people would be interested.”

ANU’s Professor Anna Moore is director of the Advanced Instrumental Technology Centre at Mount Stromlo, which designs, builds and tests satellite and space sensor systems. “It’s hard to pick an industry or company that won’t benefit in the future from being a bit more aware of what is happening on the space side of things,” says Moore.

Moore says it’s important that board directors come to grips with the potential of applications leveraging space-based technology. “The only way to benefit is to know about something as early as possible.”

While she acknowledges the froth surrounding space tourism and asteroid mining, Moore believes that more immediate and solid impact will come from satellite miniaturisation and the advent of small and comparatively inexpensive CubeSats (“U-class” spacecraft composed of multiples of 10x10x10cm cubic units). “It is really difficult to pick an industry that won’t feel an effect with regard to miniaturisation and access to space.”

Space 2.0

This is Space 2.0 for Australia. In the 1950s, Woomera in Western Australia was one of the world’s busiest space launch sites. Then the nation dropped the ball and until this year, Australia, like Iceland, was one of only two OECD countries without a space agency.

Former CSIRO boss Dr Megan Clark leads the recently formed Australian Space Agency. It has been given seed funding of $41m and a remit to craft a road map for our national civil space industry. The government’s hopes are high — it’s looking for a $12b national space industry by 2030, and 20,000 new jobs in the civil space sector.

Of course, space is not confined to civil applications. The discussion about space as an arena for war grew shriller in August when US president Donald Trump announced plans to develop a Space Force as the sixth branch of the US armed forces. Political implications aside, this seems set to accelerate further investment in an already feverish international space race. Moore says that, globally, the market is growing between 8–10 per cent a year and she foresees no slowdown over the next 50 years. She also stresses that the advent of cheaper, lighter satellites, and a newly competitive rocket launch market, means that space is no longer the province of only global giants. In addition, Australia has a unique opportunity given its location.

“Australia is such a massive country, so just from a geographic perspective its change in longitude and latitude makes it a very valuable community to work with. That means new technologies such as optical communications will benefit from that alone,” says Moore. Saber Astronautics develops machine learning solutions to monitor and manage the health of satellites and has been acknowledged by the World Economic Forum as one of a handful of companies working on technologies to deal with the escalating space junk issue. Jason Held is hugely optimistic about Australia’s opportunities.

“We have national responsibility for one-sixth of the surface of the globe — and anybody in the US who wants to talk to their satellites needs to talk in this part of the world. Australia is a big place for ground stations and operations.”

Flavia Tata Nardini is similarly ambitious. Having previously worked for the European Space Agency, Nardini is co-founder and CEO of Adelaide-based Fleet Space Technologies. The company is using remotely deployed sensors — communicating back to base via satellite — to develop solutions that “measure everything”. It could be anything from the location of cattle on far-flung stations, the amount of water in dams and moisture in the soil, to the position of mine workers in relation to the current condition of assets and equipment in order to plan and schedule predictive maintenance on a mine site.

A shoebox-sized unit, located on a pole and powered by solar panels can collect data from any sensor within a 15km radius and upload key data to a satellite, which can then transmit it to a base station for further analysis, with insights delivered direct to mine managers or farmers via smartphone.

“This new commercial space area is all about bringing value downstream,” Nardini says. “Every company, every venture, brings added value on Earth — there is huge momentum in space and all the businesses. Every director who is digitally transforming needs to look at what is happening in space because this opens up new low-cost and different industries.”

Who governs space?

Space is the new frontier for entrepreneurs such as Elon Musk (SpaceX) and Jeff Bezos (Blue Origin). Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic is signing up tourists at $250,000 a pop and a scramble of prospective asteroid mining and moon exploration companies have emerged since the US Congress passed the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act in 2015 followed by Luxembourg’s legal framework for space exploration and the use of space resources in August 2017.

No nation can claim a celestial body and space is open to all for exploration. International space laws — first developed in 1967 with the Outer Space Treaty and domestic space law from the 1990s — mean, “Space is not at all a lawless place, not the Wild West”, according to Professor Steven Freeland, dean of the School of Law at Western Sydney University.

Freeland, born the same year the USSR launched its Sputnik satellite (1957), is a member of UNESCO’s Science of Space subcommittee, a director of the International Institute of Space Law, and a member of the Space Law Committee of the International Law Association. He explains that there are five main UN treaties that guide international activities in space and make it clear space cannot be colonised. The fifth, known as the Moon Agreement, addresses how the natural resources of space, including the use of the geostationary orbit, can be exploited.

The Outer Space Treaty limits the use of the Moon and other celestial bodies to peaceful purposes, prohibiting weapons testing, conducting military maneuvers or establishing military bases. However, the treaties do not cover specifics for, say, space tourism.

However, Freeland believes that the UN treaties’ “fundamental principles will help derive an answer to a question that comes up”, with inter-nation negotiation the most likely route to solve any dispute. The International Court of Justice has yet to hear a case on space law.

Former NASA space shuttle commander Colonel Pamela Melroy GAICD, now with Nova Systems, says, “the international liability and legal framework puts all the onus on government in the Outer Space Treaty. Even if it is a commercial launch, the government of the launching state has third-party liability.”

There is discussion about whether the Outer Space Treaty needs replacing, but trying to get a multilateral agreement is very difficult, she says.

Meanwhile, more than 20 countries already have national space laws and another 20 or so are developing rules and licences for space activities. In Australia, amendments to the Space Activities Act 1998 (Cth) regarding launches and returns were passed in August 2018. Meanwhile the Australian Communications and Media Authority is being called on by local and international businesses to open the 2GHz band of the spectrum for mobile satellite providers.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content