Headline inflation ticked up marginally to 1.7 per cent in the September quarter while underlying inflation was unchanged at 1.6 per cent.

The outcome was in line with expectations but nevertheless prompted markets to slash the probability of an RBA cash rate cut next week to below five per cent. Dwelling approvals rose over September but remain deep in negative territory in annual terms. The US Fed cut rates for the third time this year as US growth dipped below two per cent in the third quarter, but the Fed has indicated that it is in no rush to cut again. Chile cancelled next month’s APEC meeting, complicating Washington and Beijing’s quest for a trade ‘mini-deal’. The UK will hold a general election on 12 December which might, or might not, resolve some Brexit uncertainty. This week’s roundup of readings and analysis includes an in-depth look at Australia’s relations with China, the RBA on central bank policy frameworks and the global drivers of low interest rates, the state of Australia’s states, the global rise of populism, Lagarde’s ECB, the challenges facing India’s Modi, and the future of US capitalism.

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

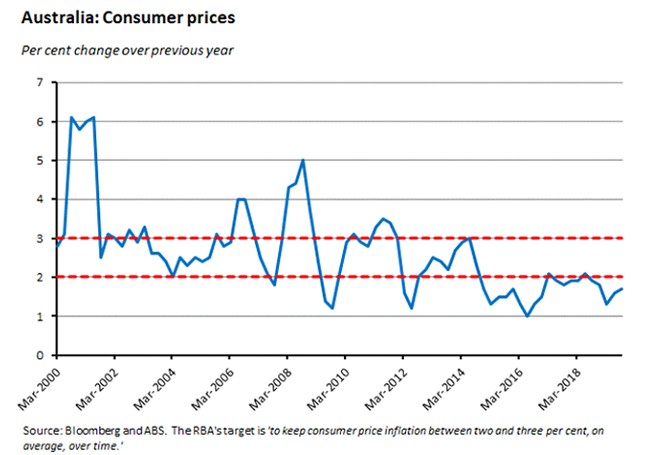

According to the ABS, Australia’s consumer price index (CPI) rose 0.5 per cent in the September quarter over the June quarter and was up 1.7 per cent over the year.

The most significant price increases for the quarter were for international holiday travel and accommodation (up 6.1 per cent), tobacco (up 3.4 per cent), property rates and charges (2.5 per cent) and child care (2.5 per cent), while the most significant falls were for automotive fuel (down two per cent), fruit (down 3.1 per cent) and vegetable (down 2.5 per cent). There were also modest falls in prices for utilities (-0.3 per cent) and new dwelling purchase for owner-occupiers (-0.1 per cent). The ABS noted that, despite those falls for fruit and vegetables, the drought was still having an impact on a range of food prices, with increases in the price of meat and seafood, dairy and related products, and bread and cereal products.

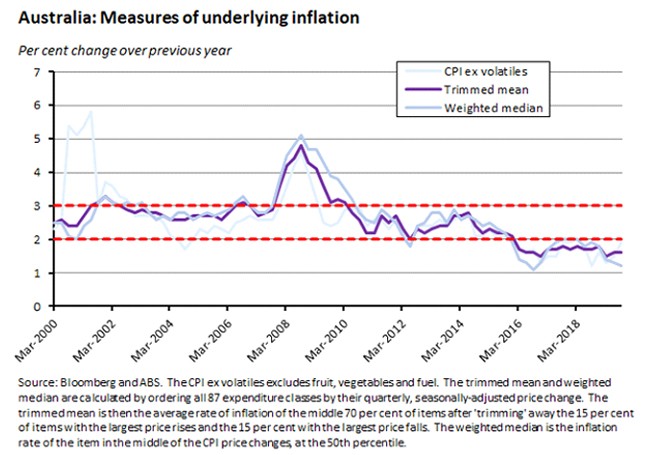

In terms of underlying inflation, the trimmed mean – generally seen as the RBA’s preferred inflation measure – was up 0.4 per cent over the quarter and 1.6 per cent over the year. The weighted median rose by 1.2 per cent in annual terms while the CPI excluding volatiles was up 1.9 per cent.

Why it matters:

The results for both the headline CPI and the trimmed mean were exactly in line with the respective consensus forecasts. They were also little changed from June’s results: the headline rate eased marginally in quarterly terms (down from 0.6 per cent to 0.5 per cent) but edged up in annual terms (from 1.6 per cent to 1.7 per cent) while the pace of quarterly and annual increase in the trimmed mean were both unchanged from the June quarter.

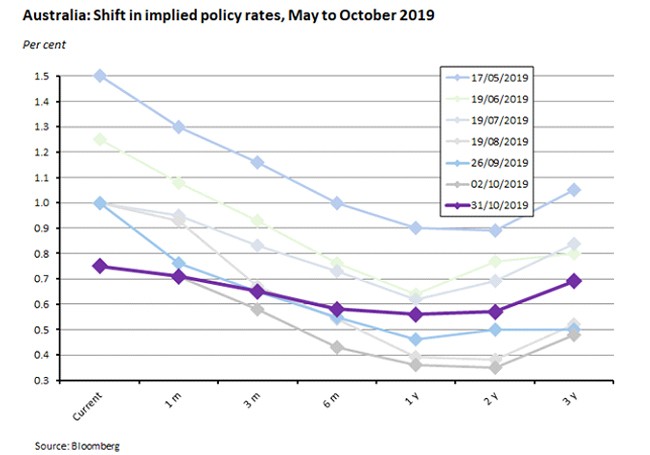

Even so, the market reaction to the inflation numbers has been to slash the odds of a rate cut at the RBA’s 5 November meeting to just 3.6 per cent at the time of writing.1 Markets have also wound back their expectations of a rate cut in December (the probability of a cut is down to 29 per cent) and in February next year (49 per cent). The implicit path for the cash rate has moved up quite noticeably as a result, with the cash rate no longer projected to fall to as low as 0.5 per cent, although the expectation is for it to still be below one per cent in three years’ time.

Meanwhile, inflation remains stuck below the RBA’s inflation target range. The headline rate has been below the bottom of the target band for all but two of the past 20 quarters while the trimmed mean has now been below two per cent for 15 consecutive quarters.

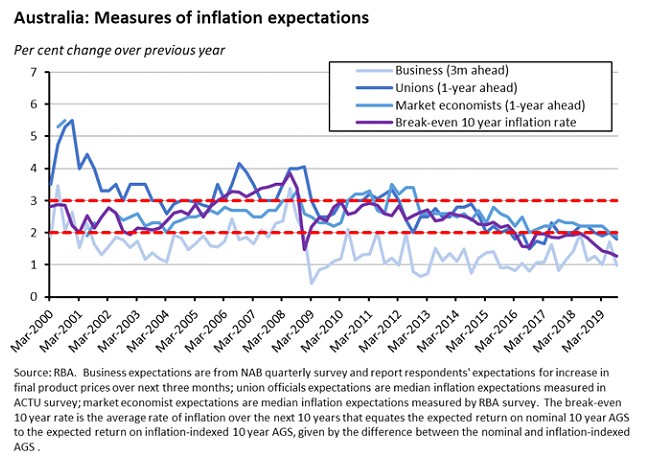

As noted in previous editions of the Weekly, that repeated failure to hit the target must inevitably raise questions about the credibility and efficacy of the current monetary policy regime. The RBA would disagree, of course, with Governor Lowe again defending the current framework in a recent speech (see this week’s readings, below). And it’s true that Australia’s version of ‘flexible’ inflation targeting does provide scope for the central bank to eschew a rigid adherence to the target. Yet the longer inflation remains below target, the greater the likelihood that inflation expectations get locked into a new and lower level, which will in turn make it that much harder to hit the target going forward.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has said he is committed to the existing target band of two – three per cent, but is reported to be considering amending the government’s agreement with the RBA to include a rule requiring the central bank to write a formal letter to the Treasurer providing an explanation in the event it misses its inflation target.

If the problem is that inflation is consistently too low, why not, as some economists suggest, just redefine the inflation target down to a lower level such as the one to three per cent band used by Canada and Norway and recover credibility that way? The complication here is that very low inflation rates can limit the scope for conventional monetary policy to affect the economy. That’s because when the central bank wants to stimulate activity, it does so by working to lower the real interest rate (that is, the nominal interest rate adjusted for inflation). But when the inflation rate is very low, the fact that the scope to cut nominal interest rate is limited by the zero bound means that it becomes difficult to deliver a low enough real rate to stimulate activity.

In fact, the logic of this particular argument is that there is a case for central banks to target a higher inflation rate in normal times, say four per cent, to give greater scope for monetary policy to react to negative shocks. More generally, the lower the real equilibrium rate of interest, the higher the ideal level of the inflation target. For many central bankers, however, the idea of a higher inflation target is unattractive in that it risks undermining the credibility they have invested in bringing down inflation to its current levels. Moreover, if policymakers already struggle to get inflation to between two and three per cent, why should we think that they’ll do a better job of getting it to (say) between three and four per cent? In this context, the RBA’s attachment to sticking with the current framework does look understandable. At least for now.

What happened:

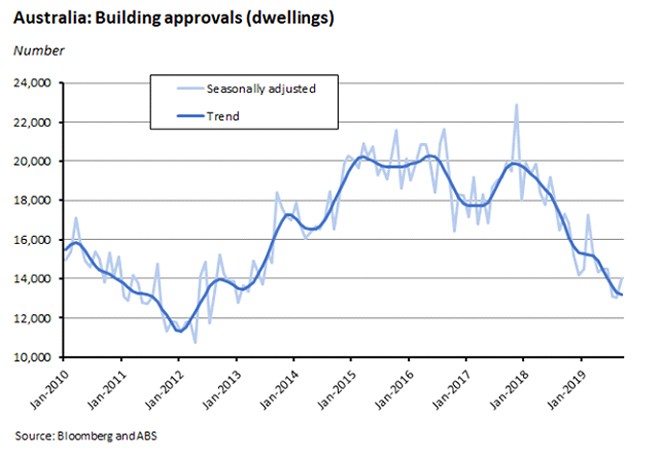

The ABS reported that dwelling approvals rose by 7.6 per cent over the month in September (seasonally adjusted) although they are still down 19 per cent over the year. The monthly bounce was the first positive result since May and reflected a 16.6 per cent monthly increase in private dwellings excluding housings and a more modest 2.8 per cent increase for private sector houses. The former was still down more than 27 per cent in annual terms, however, and the latter down more than 11 per cent on the same basis.

The monthly data are quite volatile and on a trend basis the number of approvals continued to fall, dropping for a 22nd consecutive month. But the monthly decline of 0.8 per cent was the smallest in six months.

Why it matters:

The downturn in residential construction is widely expected to remain a significant headwind for the economy. But there are some tentative indications that the turnaround in dwelling prices over the past couple of months may now be starting to at least slow the rate of decline.

. . . and what I’ve been following in the global economy

What happened:

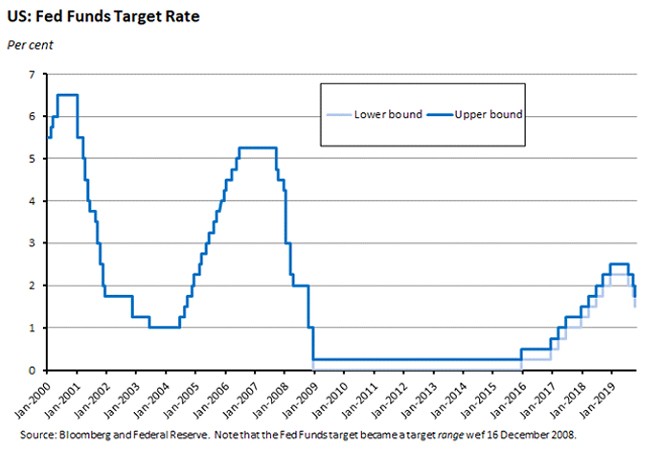

At its meeting on 30 October, the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) decided to lower the target range for the Fed Funds rate by 25bp to 1.5 per cent to 1.75 per cent. In the accompanying statement, the FOMC flagged weak business investment and exports but made the case for a rate cut in terms of ‘the implications of global developments for the economic outlook as well as muted inflation pressures.’

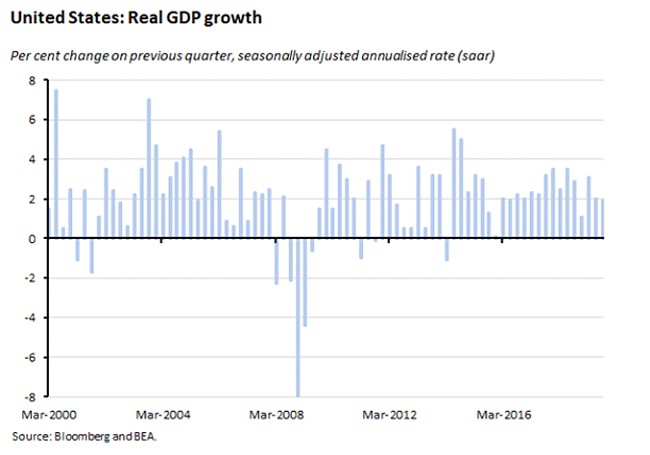

The Fed’s decision came shortly after the release of the advance estimate for third quarter GDP, which showed growth in the US economy slowing to an annualised rate of 1.9 per cent. That was down slightly from the second quarter’s two per cent rate and quite a bit weaker than the 3.1 per cent achieved in Q1. But it still beat consensus forecasts of a 1.6 per cent result.

The GDP numbers showed the US consumer continues to spend (albeit at a slower pace than in the second quarter) but that business investment spending is suffering, with a marked drop in non-residential fixed investment.

Why it matters:

This was the Fed’s third rate cut of the year, with the central bank now having delivered a total of 75bp of easing, with previous cuts coming in July and September. The Fed’s move had been widely anticipated with the market probability of a rate cut ranging above 95 per cent in the days leading up to the meeting. That meant that there was arguably more interest in what the Fed would signal about its future intentions, rather than the rate decision itself. Here, the message was that the Fed is now on hold, at least for now. In his opening remarks (pdf) to the post-meeting press conference, Fed Chair Powell said that the Fed now believes ‘monetary policy is in a good place’ and that the FOMC saw ‘the current stance of monetary policy as likely to remain appropriate as long as incoming information about the economy remains broadly consistent with our outlook of moderate economic growth, a strong labour market and inflation near our symmetric two per cent objective.’

That shift has been interpreted as indicating that, instead of the Fed aiming to cut rates unless there were signs of an improvement in economic conditions, it now plans to deliver further cuts only if future developments surprise on the downside: that is, that the bar for additional monetary policy easing has now been raised.

What happened:

Chilean President Sebastian Pinera said that the country was cancelling the November APEC trade forum and the December COP25 Climate Summit to allow the government to ‘prioritise re-establishing public order.’

Why it matters:

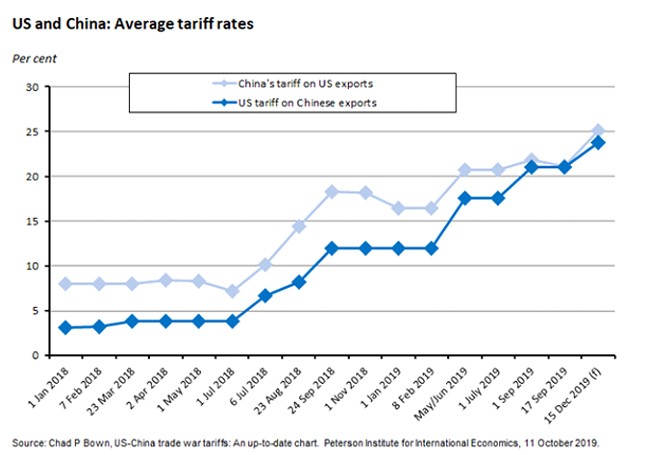

The sidelines of the November APEC meeting were supposed to provide the venue for the signing of the so-called phase one trade agreement between Washington and Beijing. Earlier this month, the United States and China had reportedly reached rough agreement on the first steps in a deal, with President Trump announcing on 11 October that he would forgo an increase on tariffs from 25 per cent to 30 per cent on US$250 billion in Chinese imports that had been due to go into effect on 15 October in return for Beijing promising that it would spend between US$40 billion and US$50 billion on US agricultural products. The APEC meeting was an opportunity for Trump and Xi to meet in person in a relatively neutral setting and then turn that rough agreement into a formal ‘mini-deal’. Moreover, the plan was that this would take place before – and therefore potentially head off – the next round of US tariff increases (15 per cent tariffs on US$156 billion of Chinese imports), still scheduled to take effect on 15 December. The cancellation complicates this timetable, as the two sides now need to find a new mutually acceptable opportunity for a meeting.

The prospect of a mini-deal has been one source of increased international economic confidence in recent weeks (the other has been an apparent decline in the risk of a no-deal Brexit: see next story) so the world economy could certainly have done without this complication.

That said, it is difficult to see the mini-deal as any kind of lasting solution to the US-China dispute given that it ignores most of the key bilateral problems. As currently reported, it will leave unresolved a range of critical issues including existing US and Chinese tariffs; US restrictions on Huawei and other Chinese technology companies; US complaints about forced technology sharing; US complaints about Chinese currency ‘manipulation’; enhanced protections for intellectual property; treatment of Chinese state-owned enterprises; and agreement on an enforcement mechanism.

Meanwhile, the average rate of US tariffs on Chinese imports is still set to double between 14 June and 15 December, even after President Trump’s announcement that he would not implement the 15 October tariff increases. China’s tariff retaliation will involve a similarly steep escalation in tariff rates.

What happened:

The UK will hold its first December election since 1923, with the country set to go to the polls on 12 December after the House of Commons voted by 438 votes to 20 to approve legislation that changes the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, meaning that voters will have to turn out for the third time since 2015.

Why it matters:

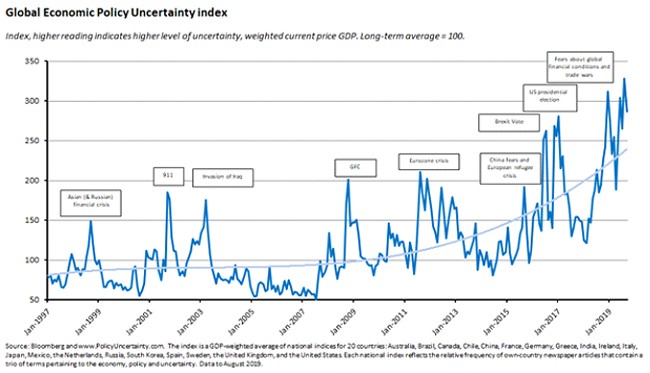

Along with the US-China trade and technology dispute, the risk of the UK crashing out of the EU without a deal has been one of the key geo-economic risks hanging over the world economy this year, contributing to the high level of global economic policy uncertainty that was highlighted by Directors in our recent Director Sentiment Index (DSI) as the most important challenge facing Australia. 2

With the EU now having granted the UK yet another extension – this time until 31 January – that risk has once again been postponed. Instead, the immediate future of Brexit is now hostage to the outcome of the UK election, where opinion polls suggest that by far the most likely outcome is a victory for Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party, which holds something like an 11-point lead over the Labour party. However, given the relative failure of those same polls to do a good job in predicting recent electoral outcomes – including the most recent UK general election (where to be fair they did get the winner right, but were quite wrong about the margin of victory) – there seem to be good reasons for taking any UK political forecasts with a large dose of salt. In other words, it’s far too early to say goodbye to Brexit-related uncertainty but we can add in some new political risks.

What I’ve been reading: articles and essays

The latest issue of Australian Foreign Affairs focuses on our relationship with China with four essays. Allan Gyngell opens by arguing that Australia has ‘never had to manage a relationship as important as the one we have with China, with a country so different in its language, culture, history and values. Nor one with an Asian state so confident and possessing so many dimensions of power.’ The consequent challenges are now testing (to destruction?) the Canberra consensus on China policy, with the result that ‘The business community…wants clarity in a situation that can’t deliver it.’ Gyngell’s prescription is to be ‘calm in the face of hyperventilation about China’, to upgrade our national resources for dealing with Beijing, and to use foreign policy and statecraft to ‘weigh and balance our interests and values.’ Richard McGregor looks at the prospect of China using economic leverage to pressure Australia, starting with David Koch’s observation that ‘If China decided to get narky with us, we go into depression. It’s a simple as that.’ McGregor doesn’t – quite – agree, arguing that China faces constraints of its own in formulating any such aggressive policy, and that while experience with Chinese tactics towards other countries does show a willingness to use economic pressure, it also suggests that Beijing is wary of the potential domestic costs involved and careful to gauge its response accordingly. Even so, he also concedes that, while ‘Beijing might not be able to tip Canberra into economic depression…there is little doubt that it has the tools to punish Australia in ways that would hurt employment in the education and tourism sectors, and hit the federal budget…Beijing could cause momentary political panic simply by targeting areas of rapidly growing trade, such as meat, wine and vitamins.’ Somewhat ominously, he also thinks that ‘sooner or later…Australia will be tested. It will be at a time and in a sector of Beijing’s choosing.’ David Uren’s focus is on the rise of national security issues in general, and of ASIO in particular, as an increasingly important player in Australia’s foreign investment regime, which raises the problem that ‘national security bodies only see foreign investment as a threat to be managed . . . [and the] experience of the past five years shows their definition of that threat is ever expanding.’ Finally, Margaret Simons examines the Chinese student boom, the magnitude of which she reckons has been large enough to change the Australian academic landscape and university funding model, markets for inner city apartments, and the nature of Australia’s migration system. As a result, ‘Australian economic, migration and education policies have become enmeshed without much evidence of clear strategic thought…So long as the business grows, the tensions and problems are hidden. But the boom almost certainly won’t last.’

In the Sir Leslie Melville Lecture, RBA Governor Philip Lowe covered two topics: the appropriate objectives of the central bank and the prevalence of very low interest rates around the world. With regard to the former, Lowe notes that the conventional wisdom on monetary policy (that the best contribution a central bank can make to full employment and economic welfare is to main low and stable inflation, and that a successful way to achieve this was via the adoption of an inflation target) has worked in delivering lower and more stable inflation rates and inflation expectations but that this relative triumph has been qualified by two considerations: (1) that low and stable inflation turns out not to a sufficient condition for financial stability and may even provide ‘fertile ground’ for the emergence of some financial stability risks and (2) technological change and globalisation have influenced inflation dynamics and made it more difficult to manage inflation. Lowe’s view is that Australia’s approach – a flexible inflation target and a broad mandate for the central bank – offers enough flexibility to meet the challenges of the current environment. Turning to the case of low interest rates, Lowe identifies a rise in global savings (ageing populations and rising life expectancy leading to more savings for lengthier retirements; the rise in relative economic importance of Asian economies with higher savings rates; previous high levels of borrowing meaning that in many economies both governments and households are reluctant to take on more debt) and a decline in global investment (high levels of global economic policy uncertainty which may also have contributed to stubbornly high hurdle rates; lower population growth; slower productivity growth) as driving some of the worldwide decline in rates, along with central bank purchases of assets that have compressed term premia. Those low global rates have constrained RBA policy actions, as if the RBA was to ‘seek to ignore these trends, the exchange rate would most likely appreciate.’ Lowe also used the occasion to again state his view that ‘it is extraordinarily unlikely that we will see negative interest rates in Australia.’

Commsec’s latest State of the States report ranks Victoria as Australia’s strongest performing economy, followed by Tasmania and then New South Wales.

The ABS reports that life expectancy in Australia has reached new record highs, with a boy born today expected to live to 80.7 years and a girl to 84.9 years. And for Australians who make it as far as the traditional retirement age of 65 years, males can expect to live a further 19.9 years and females a further 22.6 years.

Deloitte’s latest quarterly Investment Monitor considers the case for ramping up government infrastructure investment. According to the report’s lead author, Stephen Smith, there are some capacity constraints here, as ‘elevated level of current activity is already generating shortages in the skilled labour and specialised equipment needed to deliver major infrastructure projects, particularly so in Sydney and Melbourne.’ But Smith goes on to argue that ‘there are some areas where governments can do more. The current pipeline remains dominated by a series of large road and rail projects, mostly in Sydney and Melbourne, but there is still some capacity to deliver smaller scale projects outside the major capital cities. These are easier for contractors to coordinate and don’t tend to require the same amount of specialised skills and equipment to deliver.’

VoxEU has launched a debate page on the rise of populism. Guido Tabellini thinks that the nature of political conflict has changed, with the traditional economic and redistributive conflict between left and right being replaced by a new conflict pitting nationalist and socially conservative positions against cosmopolitan and socially progressive ones. Globalisation and technology have enhanced this divide ‘because winners and losers in the new economic environment are largely partitioned by the educational and cultural divide.’ Dani Rodrik distinguishes between economic and political populism to make a case that ‘economic populism may be the only way to forestall its much more dangerous cousin, political populism’. And Barry Eichengreen looks at UK data to argue that populism in general and Brexit in particular is as much about economics as it is about culture and identity.

Jens Christensen of the San Francisco Fed examines the international experience with negative policy rates across five central banks (the Danish National Bank, the European Central Bank, The Swiss National Bank, the Swedish Riksbank and the Bank of Japan) and finds there is evidence that the policy was successful in delivering an immediate and persistent response across the government bond yield curve.

An FT Big Read asks, what will Christine Lagarde’s European Central Bank look like? Lagarde will have to negotiate rising tensions around the ECB’s policies of negative interest rates (banks and insurance companies are deeply unhappy) and QE (several key members of the ECB’s governing council were bitterly opposed to Mario Draghi’s decision to restart bond purchases in September).

The challenges facing the Indian economy and India’s Prime Minister Modi have been a common theme this week. Another FT Big Read focuses on the malaise in the Indian economy, which has seen GDP growth slow from an annual rate of eight per cent in the second quarter of 2018 to just five per cent in the same quarter of this year. And the Economist has a special report on India which argues in a similar vein that India’s growth problem reflects policy failures arising from the fact that Modi has been more inclined to follow his nationalist than his reformist instincts.

‘Peak’ stories appear to be irresistible for commentators . . . and reading lists! Last week, I linked to a story about peak car. This week, Noah Smith reckons that the oil age is coming to a close. Before the US shale revolution got underway, there was a mini industry focused on writing about the possibility of the world approaching peak oil supply, but Smith thinks focus should now be on peak oil demand.

The Economist magazine has a briefing on the plans of Democratic candidate Elizabeth Warren to reshape American capitalism. Of course, Warren has yet to win the Democratic nomination, yet alone the presidency. Still, the radical nature of the proposals here and the similarly radical proposals offered by Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn in the UK (I linked to the FT’s series on those policies a few weeks back) do suggest that the possibility frontier for economic and business policies is in the process of expanding in some striking ways. Related: the same edition of the Economist looks at some of the challenges involved in Warren’s plans to break up Big Tech.

1 In part, this may have been because markets had been worried that the outcome would come in below the consensus forecasts, and so increase the chances of a rate cut. Relatively upbeat messaging from the RBA also seems to have influenced expectations.

2 Although note that the risk of Brexit on its own was ranked near the bottom of Directors’ economic concerns.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content