The RBA’s latest rate hike has taken the cash rate to its highest level in seven years and there’s more to come, which could test the resilience of the Australian economy.

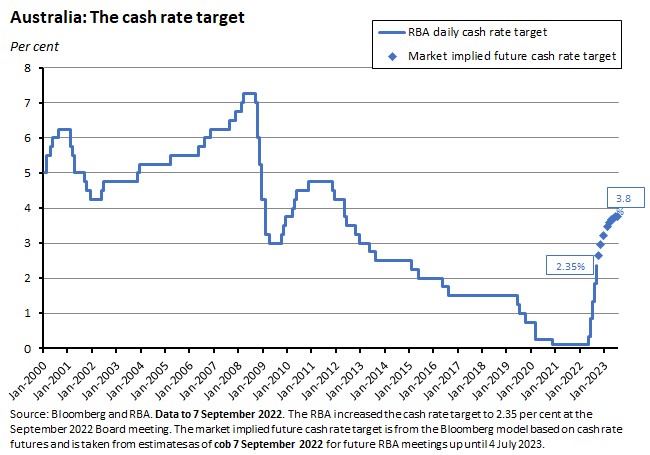

At its meeting this week, the RBA decided to increase the cash rate target by 50bp to 2.35 per cent. That fifth consecutive rate increase and the consequent cumulative 225bp of monetary policy tightening has taken the target rate to its highest level in seven years. Yet, despite having already presided over the most aggressive monetary policy tightening cycle since 1994, the central bank signalled that it isn’t done yet. Financial markets agree and are currently pricing in around 140bp of additional rate increases by the middle of next year. Further increases of that order would test the resilience of the Australian economy, although some good news here is that this week’s second quarter GDP results indicate that the economy at least entered the current phase of RBA tightening with a fair degree of momentum, confirming that the RBA has been seeking to slow a growing economy and not an already-faltering one. And the RBA governor did hint in a speech this week that the central bank is now considering easing the pace of policy tightening.

Please note that due to travel commitments, the weekly economics update will be taking a break next week meaning there will be no update on the 16 September. Normal service should resume the following week.

The RBA continues to tighten monetary policy aggressively

At its meeting on 6 September 2022, the RBA Board said it would increase the cash rate target by 50bp to 2.35 per cent. In the accompanying statement, the central bank explained that while this week’s rate increase would ‘help bring inflation back to target and create a more sustainable balance of demand and supply in the Australian economy’ it still ‘expects to increase interest rates further over the months ahead’. Despite an unprecedented five consecutive rate rises between May and September of this year, including four back-to-back 50bp hikes, and a total of 225bp of rate increases that have taken the cash rate target to its highest level since early 2015, the central bank is still not done with monetary policy tightening.

Currently, the RBA’s assessment is for inflation to peak later this year and then decline back towards the two-three per cent target range, with the central forecast ‘for CPI inflation to be around 7.75 per cent over 2022, a little above four per cent over 2023, and around three per cent over 2024.’ The central bank also expects the unemployment rate to fall below July’s 3.4 per cent over the months ahead before increasing again as the economy slows.

Most market economists had expected this week’s 50bp hike, but there had been some debate as to whether the RBA would also signal a forthcoming moderation in the pace of monetary policy tightening. Readers might recall that the analysis of the RBA’s August rate hike in the 5 August weekly note speculated that, as the actual level of the cash rate target approached the ‘neutral’ rate of around 2.5 per cent (on the concept of neutral, see the detailed discussion in the 22 July weekly note), the size of future rate increases could be scaled back from the current outsized 50bp jumps to more modest 25bp adjustments, perhaps by the 4 October meeting. The text of this week’s statement offered relatively little new guidance on this point. Granted, it did note again that while more rate increases were likely, the bank was ‘not on a pre-set path’. Perhaps more importantly, it dropped the reference to ‘a further step in the normalisation of monetary policy’, suggesting that the cash rate is indeed now close to neutral. And the statement also remarked that the ‘size and timing of future interest rate increases will be guided by the incoming data and the Board’s assessment of the outlook for inflation and the labour market.’ But there was no direct mention of a possible slowdown in the pace of rate increases.

Is the RBA in now danger of overdoing policy tightening? This week’s statement did flag that an important source of uncertainty on this front was the behaviour of household spending. On the one hand, higher inflation and higher interest rates are both now squeezing household budgets, surveys report that consumer confidence is at low levels, and house prices are falling at an increasing pace. On the other hand, however, the RBA sees that unemployment is low, job vacancies are high, it is expecting wage growth to pick up further, and many households have built up large financial buffers during the pandemic which should allow them to sustain spending in the face of current pressures. Supporting this view, the June quarter GDP numbers and July’s data on retail turnover and consumer spending (see below) show that consumer spending has remained strong over the first seven months of this year.

Another important complicating factor here is that monetary policy is famously subject to ‘long and variable lags’ – on some estimates, it could take between one and two years for changes in the cash rate to have their maximum effect on economic activity and inflation. When the RBA is playing aggressive ‘catch up’ with interest rates, like now, those lags increase the risk of policy overshooting. That risk helps make the case for some easing in the pace of rate hikes as the RBA moves from a neutral to a contractionary setting for the cash rate target. Market pricing, meanwhile, continues to predict a cash rate comfortably north of three per cent by year-end and approaching four per cent in 2023. If realised, that would see the cash rate back at early 2012 levels and would represent a significant test of the economy’s resilience to high interest rates.

Interestingly, in a speech this week on inflation and the monetary policy framework given after the RBA Board meeting, RBA Governor Lowe did acknowledge elements of this argument. After again characterising the path involved in taming inflation while also keeping the economy on an even keel as ‘a narrow one and…clouded in uncertainty’, he concluded his prepared remarks by noting:

‘We are conscious that there are lags in the operation of monetary policy and that interest rates have increased very quickly. And we recognise that, all else equal, the case for a slower pace of increase in interest rates becomes stronger as the level of the cash rate rises. But how high interest rates need to go and how quickly we get there will be guided by the incoming data and the evolving outlook for inflation and the labour market.’

Those comments do appear to allow for the likelihood of a move towards smaller-sized monthly interest rate hikes in the future, although the caveats relating to the nature of the data flow and the evolving outlook imply that the timing of this change has yet to be locked in.

GDP growth was healthy in the second quarter of this year

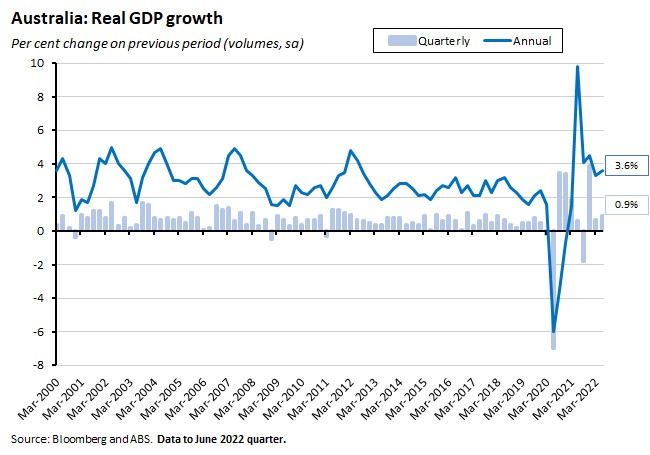

Moving from looking forwards to the next RBA rate decision to looking back at the economy’s performance earlier this year, the ABS said this week that Australia’s real GDP rose by 0.9 per cent in the June quarter 2022 (seasonally adjusted) to be up 3.6 per cent on the June quarter 2021 outcome. GDP per capita rose 0.5 per cent quarter-on-quarter and 2.7 per cent year-on-year. For the 2021-22 as whole, real GDP rose 3.9 per cent, recording the strongest pace of annual growth since 2011-12.

Real economic growth in the June quarter was powered in large part by household consumption spending, which contributed 1.1 percentage points to quarterly GDP growth. Household consumption grew 2.2 per cent over the quarter and by six per cent over the year as households increased their spending on discretionary services: the easing of travel restrictions boosted expenditure on transport services (up 37.3 per cent over the quarter) and there were also increases for hotels, cafes and restaurants (up 8.8 per cent) and recreation and culture services (up 3.6 per cent). All up, spending on discretionary services was up 3.9 per cent over the quarter and 11.9 per cent in annual terms. Spending on all services rose 3.6 per cent in the June quarter and 7.3 per cent through the year, exceeding pre-pandemic levels for the first time. In contrast, spending on goods edged down by 0.1 per cent.

Growth in household spending outpaced the more modest rise in household incomes in the June quarter, and as a result the household saving ratio continued to decline, falling from 11.1 per cent in Q1:2022 to 8.7 per cent in Q2:2022, although it remains elevated relative to pre-pandemic levels.

Other components of domestic demand were relatively subdued. Government consumption fell 0.8 per cent over the quarter, subtracting 0.2 percentage points from GDP growth, as state governments wound back their expenditure on health; dwelling investment fell 2.9 per cent in quarterly terms and 4.6 per cent in annual terms, with the ABS citing wet weather across much of the east coast together with continued material and labour shortages as hampering construction activity, subtracting a further 0.1 percentage points from overall growth; and private business investment fell 0.8 per cent quarter-on-quarter and detracted a further 0.1 percentage points from growth, although it was up 1.7 per cent year-on-year. In addition, the pace of inventory build-up slowed from $7.8 billion in March to $1.6 billion in June, detracting 1.2 percentage points from quarterly GDP growth.

The other big driver of second quarter growth was found on the external side of the national accounts, where net exports contributed one percentage point to quarterly GDP growth. Exports of goods and services rose 5.5 per cent over the quarter and 4.9 per cent over the year, while imports of goods and services edged up 0.7 per cent quarter-on-quarter and rose ten per cent year-on-year. The quarterly increase in exports was the strongest result since the Sydney Olympics in Q3:2000.

Turning from the real (volume) numbers to the nominal results, nominal GDP rose by a robust 4.3 per cent over the quarter and surged 12.1 per cent over the year. In a sign of the strong price pressures in the economy, the implicit GDP deflator rose 4.3 per cent quarter-on-quarter and 8.3 per cent year-on-year. Rising commodity prices meant Australia’s terms of trade rose 4.6 per cent over the quarter to set a new record high in the June 2022.

Other notable results from the national accounts release this week included:

- GDP per hour worked (labour productivity) grew 2.1 per cent over 2021-22. That was the fastest rate of annual growth seen in a decade.

- The ABS estimates that the level of Australia’s real GDP has suffered a cumulative loss of $158 billion compared to its pre-pandemic trajectory.

- The Bureau also calculates that, since the pandemic began, households have spent $148 billion less than a continuation of their pre-pandemic spending trajectory would have implied; gross disposable incomes for households have experienced a cumulative gain of $75 billion; and government consumption an additional spend of $42 billion. Higher disposable incomes and reduced spending have together allowed households to accumulate an additional $225 billion in savings since the onset of COVID-19.

- Compensation of employees (COE) rose 2.4 per cent over the quarter and seven per cent over the year in Q2:2022, with wages and salaries up 2.5 per cent in quarterly terms and 6.7 per cent on an annual basis. The number of employed persons rose 0.9 per cent and average COE per employee rose by 1.4 per cent over the quarter.

- Boosted by very strong mining profits, the share of national income going to business profits hit a record high of 32.9 per cent in the June quarter of this year, while the share going to labour was just 48.5 per cent – the lowest proportion on record.

Taken overall, the second quarter GDP results tell us that the real economy was in decent shape in the second quarter of this year, albeit mainly thanks to catch-up spending by households and a strong export performance. They also report strong nominal growth, not least due to record high terms of trade on the back of high commodity prices. That means that the RBA’s efforts to lift interest rates (there was a total of 75bp of rate hikes in Q2:2022) got underway against a backdrop of relatively robust economic activity. Of course, there have been a further 150bp of rate increases since then, and that timing – along with the lags involved in the monetary policy transmission mechanism – means that the second quarter national accounts have little to tell us about the likely overall impact of current and future policy tightening.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

ANZ Job Advertisements rose two per cent over the month in August, nudging higher than their March 2022 peak to reach 242,301. Back at the time of the July release, ANZ economists had hypothesised that the job ads series had passed its peak and so this month they duly noted that the August result had proved them wrong, with the result indicating that labour market demand remains robust, even in the face of multiple interest rate increases from the RBA.

The ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index rose 1.3 per cent last week, taking the index up to its highest level since early June this year. Confidence was up in Victoria, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia but flat in New South Wales. ANZ noted that confidence data by housing status showed that for people renting a home, confidence jumped last week and is now at a higher level than it was before the RBA started to increase rates. However, for people paying off a mortgage (down 19 per cent) and for those who own their own home (down 13 per cent) confidence is sharply lower since the RBA’s first cash rate hike back in May. And despite this week’s lift, the level of confidence remains in deeply negative territory. Meanwhile, household inflation expectations rose 0.1 percentage point over the week to 5.4 per cent.

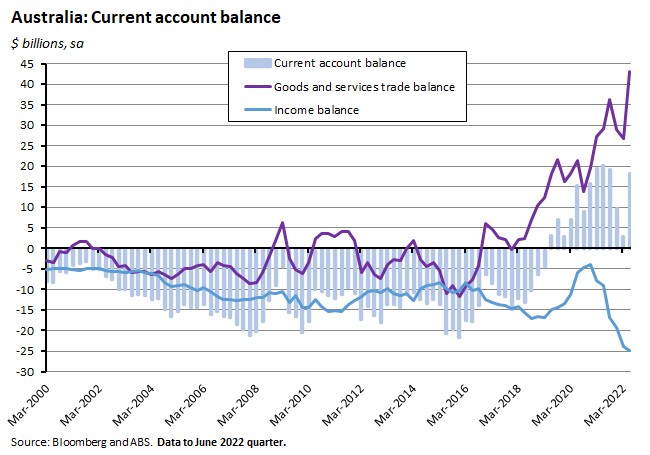

The ABS reported that Australia’s current account surplus increased from $2.8 billion in the first quarter of this year to $18.3 billion in the second quarter, with the country recording a 13th consecutive current account surplus (after having previously run 175 consecutive quarters of deficits). The $15.6 billion increase for the June quarter was powered by a $16.3 billion increase in the goods and services trade surplus, which rose to a record $43.1 billion. Exports of goods and services rose 14.7 per cent, lifted by rising commodity export prices, which also saw Australia’s terms of trade rise 4.6 per cent and set a new record. The Bureau said that in 2021-22, exports of coal, coke and briquettes exceeded $100 billion for the first time. The increase in the trade surplus was more than enough to offset a wider deficit on the primary income account, the latter reflecting increased profits in the resources sector producing higher dividend payments to foreign investors.

Corresponding to the current account surplus was an outflow on the capital and financial account in the form of a deficit of $18.9 billion, driven by a financial account deficit of $18.7 billion. There were net outflows of $17.1 billion of debt and $1.6 billion of equity. Australia’s net international investment position was a liability of $834.4 billion in the June quarter, $19.1 billion smaller than the March 2022 result. Australia’s net foreign equity asset position increased $34.4 billion to $323.3 billion while our net foreign debt liability position rose by $15.3 billion to $1,157.7 billion.

According to the ABS, Australia’s monthly trade balance on good and services was a surplus of $8.7 billion in July this year. That was down $8.4 billion from June’s record $17.1 billion surplus. The shrinking in the surplus reflected a $6.1 billion (9.9 per cent) fall in the value of goods and services exports, driven by declines in the value of exports of coal, coke and briquettes (down $2.5 billion), of metal ores and minerals (down $2.3 billion) and of non-monetary gold (down $1.2 billion). Imports of goods and services rose $1.7 billion (4.6 per cent) over the month.

Australia’s general government net operating balance rose by $15.5 billion to a surplus of $13.2 billion in the June 2022 quarter, up from a deficit of $2.2 billion in the March quarter. According to the ABS, taxation revenue rose 14.5 per cent over the quarter taking total general government revenue up by 14.2 per cent. Total general government expenses rose 6.6 per cent over the quarter. The lift in revenues reflected improved economic conditions, which boosted receipts from company income tax and personal income tax along with a rise in royalty income from higher commodity prices. Note that this is, of course, consistent with the strong nominal GDP and profit growth recorded in the June quarter national accounts noted above.

The ABS said that household spending – as measured by its experimental monthly household spending indicator – continued to rise in July 2022. It rose 18.4 per cent through the year (current price, calendar adjusted basis), with spending up for both services (28.4 per cent) and goods (9.5 per cent). That marked the 17th consecutive month of year-on-year rises in total spending. Discretionary spending was up 19.8 per cent through the year while non-discretionary spending rose 17.1 per cent, and there were particularly large increases on categories that had seen spending restricted last year due to lockdowns: clothing and footwear (up 45 per cent), transport (up 35.4 per cent) and hotels, cafes and restaurants (up 34.9 per cent). Again, this is consistent with the pattern of spending seen in the April to June period as described in the national accounts. Spending was also 11.9 per cent higher than pre-pandemic July 2019 estimates.

The latest weekly payroll jobs and wages data from the ABS showed that the number of jobs fell 0.4 per cent between the weeks ending 30 July and 13 August 2022 while total wages paid over the same period were down 1.4 per cent. Over the past month, job numbers were down 0.8 per cent and wages down 1.9 per cent, with jobs falling in all industries except for education and training. The industries with the largest share of job falls were the construction industry and professional, scientific and technical services. Payroll job numbers have been sliding since the end of June this year, which the ABS attributes to the impact of short-term employee absences due to COVID-19 and other illnesses over the winter period. The Bureau explained that payroll jobs can show slower growth and larger short-term changes than the ABS Labour Force statistics on employment, as employees without paid leave entitlements may still be away from work for a short period without losing their job, particularly during holiday periods or when they are sick. It also issued its regular caution that it can be difficult to interpret changes in payroll data around the end of the financial year, because of changes in employers' reporting patterns.

New ABS Business Indicators showed company gross operating profits rose 7.6 per cent (seasonally adjusted) over the June quarter to be up 28.5 per cent over the year while wages and salaries were up 3.3 per cent quarter-on-quarter and 6.8 per cent year-on-year. Mining profits drove much of the increase in overall profits, up 14.3 per cent over the quarter, while wages and salaries in the industry were up 2.4 per cent. Growth in quarterly profits was extremely strong in the accommodation and food services industry (up 48.8 per cent) and transport, postal and warehousing (up 23.8 per cent).

Data from the ABS on the number of industrial disputes showed that there were 154 disputes in the year ended June 2022 with a total of 234,600 working days lost. That was 54 more disputes than in the previous year and 176,900 more working days lost. In the June quarter alone, there were 53 disputes involving 73,700 employees and 128,100 working days lost. That marks the largest number of working days lost in a single quarter since the June quarter of 2004.

On this week’s Dismal Science podcast, we ask if the protests will shake the Reserve Bank’s confidence, dig into the latest GDP data for Australia and look at persistent inequality in China.

Other things to note . . .

- The RBA Governor’s speech on inflation and the monetary policy framework referenced above also included a defence of the flexible inflation targeting approach that is at the heart of the central bank’s policy framework. Governor Lowe argued that ‘the strong nominal anchor and the flexibility provided by flexible inflation targeting will both be very helpful’ in managing current economic circumstances, adding that these ‘attributes are difficult (although not impossible) to replicate with another monetary policy regime.’ But he did suggest that it would be useful for the current Review into the central bank to consider the case for revisiting the two-to-three per cent inflation target band, and that it could also examine how the central bank manages and communicates the trade-offs between inflation and growth, and between inflation and macro and financial stability risks.

- The RBA also published the September 2022 edition of its regular chart pack on the Australian economy and financial markets.

- The ABS lists 16 things that happened in the Australian economy in the June quarter 2022.

- ABARES’ Agricultural Outlook for the September quarter 2022 predicts that the value of agricultural exports will be a record $70.3 billion in 2022-23, driven by crop exports. Grain exports in particular are running at record pace following successive large winter crops, with the value of Australian wheat exports forecast to reach $11.7 billion due to a combination of bumper production and high international prices. Beef exports are forecast to rise to $10.2 billion in 2022-23 while the value of cotton exports is forecast to reach a record $7 billion, making it the third most valuable agricultural export commodity after wheat and beef – its highest ranking on record .The gross value of total agricultural production is forecast to fall four per cent to $81.8 billion in the same year.

- Ross Garnaut’s address (pdf) to last week’s Jobs Summit.

- ABC Business explains why the federal government is interested in pushing multi-employer bargaining.

- The Boston Review on US monetary policy and the Education of Ben Bernanke.

- The WSJ says that a slowing China is tempering global inflation pressures.

- Last week, I linked to two columns from Richard Baldwin on the peak globalisation myth. The third and fourth columns in this series are now up: the third tracks the unwinding of global supply chains while the final column says that international services trade has not peaked.

- The September 2022 edition of the IMF’s Finance & Development magazine focuses on a new era for money and includes essays on making sense of crypto, central banks and fintech, and regulatory challenges.

- GMO’s Jeremy Grantham argues that we may be entering the supperbubble’s final act.

- The Economist asks, why haven’t the digitisation and new ways of working prompted by the pandemic boosted productivity growth? The good news is that the boost may still be coming: there’s often a lag of three to five years between increased business investment and productivity growth. But set against that hope is that much recent corporate investment is focused not on lifting productivity but rather on building inventory and increasing resilience; that the long-term impact on productivity from WFH remains uncertain; and that the pandemic has introduced new headwinds, such as more workdays lost to sickness.

- Also from the Economist, how La Nina and climate change have combined to deliver a year of extreme weather.

- An FT Big Read on Europe’s new dirty energy and the ‘unavoidable evil’ of wartime fossil fuels.

- The Atlantic magazine reviews the new economic history book from Brad Delong. My copy has just turned up in the post.

- The Australia in the World Podcast considers Australian foreign policy and the Taiwan issue.

- Related, two episodes from the Sinica podcast. First, Bloomberg Chief Economist Tom Orlik on whether China’s bubble is finally about to pop. Second, Jessica Chen Weiss on Avoiding the China Trap.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content