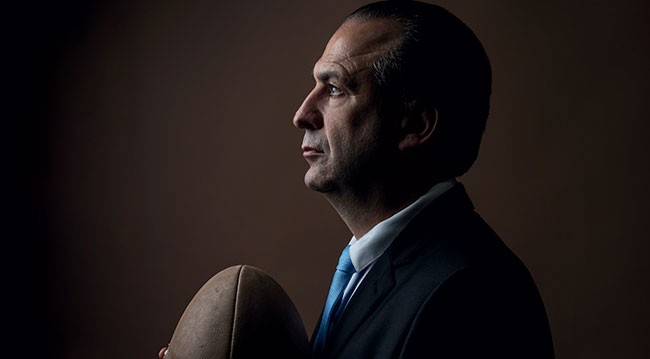

Australian Rugby League Commission chair Peter V'Landys AM was determined to get league back on TV during the coronavirus lockdown. Here's how he and the board managed it.

In the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, Australian Rugby League Commission (ARLC) chair Peter V’Landys AM was single-minded in his drive to get the game he loves back on the field, seemingly twisting the arms of politicians, health authorities and broadcasters at will. The self-described “bogan from Wollongong” — other descriptions include “human bulldozer” — elbowed the NRL competition back into the nation’s living rooms weeks before any other major sporting code. V’Landys had crashed through, but detractors labelled his modus operandi unorthodox, even irresponsible.

As COVID-19 spread, threatening to send rugby league broke, V’Landys was conducting Zoom meetings with the five commissioners on the ARLC board — Tony McGrath MAICD, Prof Megan Davis, Peter Beattie AC, Wayne Pearce OAM and Dr Gary Weiss AM — outlining his ambitious targets for the game’s relaunch. From 19 April to 19 May, they hooked up eight times, twice on a Sunday, as the ambitious 28 May deadline for resumption loomed.

“He is a driver of ideas, a can-do person, but he runs his ideas in front of the board for approval,” says the former Queensland premier Peter Beattie, the man V’Landys replaced as chair in October 2019.

Davis and former Balmain Tigers legend Pearce agree. “No-one wants groupthink. Peter’s very respectful of the different skills commissioners bring to the table,” says Davis. “He is all about stretching yourself beyond your comfort zone,” adds Pearce.

By 27 March, rugby league had no comfort zone. The NRL season had been shut down because of the pandemic and its free-to-air partner Nine Entertainment was telling shareholders it would save $130m if the 2020 campaign was axed. Broadcast rights make up nearly 70 per cent of rugby league’s revenue, and any shortfall could have pushed poorer clubs to the brink. The code was on a financial precipice.

McGrath, a receivership/restructuring professional, and an ARLC commissioner since 2014, says talk of catastrophe was not hyperbole.

“We went into the COVID period with quite a strong balance sheet and very liquid position ($120.662m in total equity, according to the 2019 NRL annual report, but actual cash of about $70m) which was really helpful, and the minute we couldn’t play football, it put our broadcast contracts at risk and it put all of our clubs at risk. No-one has a balance sheet strong enough to cope with a complete decimation of your business model. Look at Qantas.”

V’Landys had expected to be a low-profile chair, but the biggest emergency in the game since the Super League competition of the 1990s thrust him into the spotlight. As CEO and a board member of Racing NSW, positions he still holds, V’Landys had successfully guided the industry through the equine influenza outbreak of 2007, so he had first-hand knowledge of biosecurity protocols and infection minimisation. And he’d kept the sport of kings running as the nation slumped into self-imposed hibernation. With then NRL CEO Todd Greenberg reportedly on the nose with Nine and at loggerheads with the clubs — he ultimately resigned on April 20 — it was up to V’Landys to steer the game back to financial health and long-term prosperity. And if that meant adopting the role of board strongman or “mongrel” in order to save the game he had played as a boy from possible extinction, then so be it.

“I’m not frightened to say that at times I can be forceful,” says V’Landys, reflecting on the crisis. “Not so much as a mongrel, but as a person who doesn’t tolerate negativity. I prefer people who have a ‘how can we do something’ attitude, to people who find 100 reasons why you can’t do it.”

In Pearce, he had the ultimate can-do ally, a man whose experience on the football field as a lock forward steeled him for the avalanche of criticism that would follow. “Peter is action-orientated — he sits in the space of challenging but doable,” says Pearce of his chair’s ability to effect change. “Because he is still in an executive role in another part of his life, it gives him a strong understanding of the operational side.”

V’Landys appointed Pearce head of Project Apollo, a committee of key stakeholders tasked with restarting the premiership at the earliest possible date. They knew every week the NRL languished off-screen, millions of dollars in revenue were being lost. “We were prepared to aim for a stretched return target date with the view of a massive upside if we got it,” says Pearce. “If we didn’t quite hit it, we could just slot the date back a week or two.”

Apollo advisers included Professor David Heslop, an associate professor at the UNSW School of Public Health and Community Medicine and a military doctor with expertise in biosecurity; GP and HIV researcher and infectious disease expert Dr Cassy Workman; and former Caltex environmental decontamination expert Shane Healey. They gave the taskforce the credibility it needed to convince governments that restarting the competition wouldn’t put the wider community at risk.

If V’Landys is widely perceived as a warrior, facts, as he sees them, are always his primary weapons in battle. “The secret is to have every bit of available information at your disposal and do your research, do your homework, because you’ll be caught out if you don’t. You have to know your subject extremely well — not just on the edges.”

With borders being closed to foreigners, a source of more than 60 per cent of infections at the time, V’Landys was confident (based on research carried out by staff) the infection rate would be less than one per cent by 28 May (an indicator that the outbreak is under control). “We monitored infection rates 24/7, read the latest medical literature and monitored infection rate patterns and trends in other jurisdictions,” says Davis.

That analysis enabled V’Landys to build a case for an accelerated resumption, then practise what he does best — leverage contacts to have that case prosecuted at the highest level. The New Zealand Warriors were critical to Project Apollo’s plans. Without the Auckland-based side, the NRL could not provide eight weekly games for television. V’Landys had the idea of quarantining them for two weeks while they trained in the NSW country town of Tamworth. But opening up the border for rugby league players caused some official disquiet.

What the AFL did

The AFL moved fast to manage the risk from a rise in COVID-19 cases in Victoria in early July.

Just days before the NSW/Victoria border closed on 8 July and Melbourne increased lockdown measures for six weeks, eight Victorian AFL clubs relocated to NSW and Queensland. Two other Victorian teams had already relocated to WA. Players were warned to adhere to quarantine conditions.

In late April, NSW Health Minister Brad Hazzard said the NRL was required to discuss with health authorities how resuming play could be done safely. “If it is possible for any sport to operate in a safe way, that’s a question for health authorities not politicians and if the organisations want to talk to them about that, that’s a matter for them,” he said. “If we could be watching rugby league sitting at home, yeah I’d like it, but we’ve still got to make sure the teams are safe, the people coaching are safe — and the people who make those decisions are the health authorities.”

Prime Minister Scott Morrison was more direct. “Authority has not been provided and no amount of reporting it will change that decision,” he said on 30 April. The deputy chief health officer, Paul Kelly, had previously warned that the NRL should not be considered to be “a law unto itself”.

Writing in The Conversation on 28 April, Keith Rathbone, a sports history lecturer at Macquarie University, noted, “Asymptomatic carriers could be the biggest problem for the NRL. A study in the British Medical Journal and a World Health Organization report suggested four-fifths of infected people may be asymptomatic. [Using] apps to check temperatures and player health might miss those who are infected, but not showing symptoms.”

V’Landys wasn’t deterred. He contacted business friend Paul Whittaker, the head of Sky News, and Ray Hadley, the influential 2GB announcer. They lobbied and opened doors on his behalf. Two days later, the Warriors were allowed to enter the country.

“A good CEO is a person who has built up relationships and who can contact people when you need them most — and that’s what I did,” says V’Landys. “I used the people I had met over the years and are in positions of influence, and asked them to assist me. But at the end of the day, you’ve got to have a good, strong case. It’s no use using your connections if your case is flimsy.”

The pace of reform astounded the Daily Telegraph’s Phil Rothfield, who has covered rugby league for more than 40 years. “In the old days, it used to take three weeks to make a decision,” he says. “But if Peter thinks he’s got a good idea, he’ll go to the NRL management and he’ll implement the idea the next day.”

It also impressed ABC sports reporter Tracey Holmes. “V’Landys has looked like he has done the best out of all the sports administrators during COVID-19. I wouldn’t describe him as guiding the game through... more as a bull at the gate.”

V’Landys on board dynamics

“In my view, a lot of boards rely too heavily on management. There has to be a balance. Boards should bring their own ideas and style — there are lot of boards that don’t do that. They should be more hands-on in ideas and strategy, not operationally. Otherwise, management becomes the board. Most boards will relate to this — most of the decisions are recommendations from management. There has to be a balance. If you’re going to be on a board, you have to make a contribution with ideas that are going to take the business forward. The secret with boards is they are all a team and you are the captain of the team. Every one of those board members has something to contribute. You take advantage of that, see what they’re good at, what they specialise in, what they bring to the table, and you harvest it. Like a sporting team, you have different players who have different skills — and you take advantage of those skills and players at different times.”

Some AFL figures, used to their game being the nation’s pace-setting code, were unimpressed by the NRL’s rapid manoeuvrings. Hawthorn president Jeff Kennett AC labelled V’Landys’ actions in fast-tracking the NRL’s return “irresponsible”.

“It made me laugh,” says V’Landys of Kennett’s criticism. It also highlighted one of his key lessons from the past three months. “Don’t listen to the white noise, because there is nothing that you do that won’t attract criticism from negative people. Just move forward and keep going. Be brave.”

But V’Landys had bigger fish to fry than an ex-Victorian premier. Crucial talks with Channel Nine and Fox Sports over a new broadcast deal were foundering as networks — faced with declining revenue from advertising dollars and increased competition from streaming services — sought to reduce costs. Nine publicly hit out at the NRL management, accusing it of squandering millions of dollars in broadcast money and running a “bloated head office”.

With the relationship between CEO Greenberg and Nine strained to breaking point, V’Landys took on a quasi-executive chair role, intervening to rebuild trust. But first he had to shrug off accusations that the NRL’s operating costs, which many viewed as extravagant, had developed under his watch. “I’ve only been a director for the past two years and I always said the cost structure was unsustainable,” he says. “The budgets were always scrutinised and I never quite accepted them. The coronavirus gave us the opportunity to reset the business and take away costs that shouldn’t be there.”

At a press conference, V’Landys and Greenberg announced the NRL’s intention to slash operating costs by 53 per cent, including a 95 per cent reduction in staff and 25 per cent reduction in executive salaries during the coronavirus shutdown. Players agreed to a 71 per cent pay cut.

“The ARLC will lead by example in substantially reducing its costs now and into the future,” said V’Landys at the time.

Greenberg, who had upset Nine by secretly discussing television rights with Channel Seven, was now sidelined as broadcast negotiations gathered pace. When he fell on his sword, reportedly at the behest of an unhappy board, although V’Landys does not want to get into specifics, chief commercial officer Andrew Abdo stepped in as acting CEO, to help conclude what V’Landys had described as “brutal” negotiations. The result was a reduced short-term deal with Nine, reflecting the drop-off in content due to the virus, and an extended contract with Fox until 2027, which gave the game, and its clubs, certainty as it emerged from COVID-19. But some complained the code had undersold itself. Beattie disagrees.

“That’s obviously bullshit,” he says. “We live in the most uncertain media environment since TV came to Australia. We got the best deal we possibly could. Yes, we had to accept a small discount... but we had to get something that drove rugby league ahead and took our partners with us.”

One of Nine’s most trenchant criticisms of the NRL was that the game had become robotic and predictable as a television product, which showed up in falling ratings. V’Landys was stung by the assessment. Rothfield describes V’Landys as the most fan-friendly administrator he has known, a guy who “loves stopping in the street and talking to the punters.”

V’Landys has never forgotten that sport is an entertainment business. “People watch rugby league to escape, so you’ve got give them what they want,” he says. “People have X amount of disposable income and they’re going to use that for entertainment — and there is a lot of competition for entertainment.”

Seizing on the results of a fan survey undertaken by the NRL’s competition committee at the end of last year, V’Landys vowed to speed up the game by ditching the unpopular second referee and announcing a six-again tackle rule on 13 May to eliminate wrestling around the ruck. Referees choked on their whistles, even threatening strike action. Coaches and players expressed reservations about tampering with rules just two games into a season. The proposals seemed dead in the water.

V’Landys says determination is the most underrated quality in a leader. “If people can see you’re determined, they come along for the ride.”

First, Wayne Pearce, a fierce advocate of the need to make rugby league more entertaining, then the rest of the commission, saw the merit in V’Landys’ argument. After the 28 May competition restart, the press hailed the rule changes as ratings soared and a more attractive brand of rugby league filled television screens. Even critics conceded they had had a positive effect. “Peter has a knack of backing the right horse,” says Pearce. “He has an intuition.”

In some ways, the coronavirus was a gift to rugby league. It dramatically exposed the code’s faultlines and presented V’Landys and the ARLC with the opportunity to repair them. “For us, the coronavirus wasn’t destructive, it was a health virus,” says Beattie. “We are so much more cohesive and together.”

Unsurprisingly, V’Landys agrees. “I always use the analogy that the game is a family. You’re always going to have fights within the family, but at the end of it, you have to stick up for each other, and I think the family has never been more united.”

Clubs, players and other stakeholders have increasingly warmed to V’Landys’ combative but consultative style. “Peter has embedded the norm of consultation into the business,” says Davis. “And this means listening and responding to what people want, their ideas to grow the game, their concerns when things are going well, and when they’re not.”

V’Landys is not complacent. He knows there has never been a more taxing time for professional sports administrators. Financially, he says, rugby league must get rid of the “nice-to-haves” and keep the “must-haves”. Payments to prop up cash-strapped clubs during the pandemic will not continue indefinitely, and broadcast rights will be a dogfight for the foreseeable future.

McGrath says the new reality is that sports organisations have to be leaner, more cost-effective and streamlined structures. “We have to be smaller. The NRL has a broad mandate, including fostering rugby league at the grassroots level, and we’re going to have to put some of that on hold in the next couple of years to survive. [Before] we were certainly meeting our objectives, but we were doing it in a manner that could have been done for less money.”

As a boy, V’Landys’ favourite player was a St George Dragons utility back known as “Lord” Ted Goodwin for his uncanny ability to pull off miraculous plays. It is a stretch to suggest V’Landys has performed miracles, but there is little doubt that under his stewardship the game possesses a self-confidence and long-term vision that only months ago seemed unthinkable.

“You need strong leadership in a crisis,” says acting CEO Andrew Abdo. “I was keen to work with Peter because I could learn a lot from him — about how he drives change and innovative thinking. He made it clear we were on a burning platform and we needed to act, he articulated clear objectives, and he mobilised people to help achieve those objectives. Peter was the owner of the May 28 vision. While others jested and thought it couldn’t be done, he was relentless.”

With this particular mission accomplished, V’Landys is already pondering new frontiers. “The most pressing challenge facing sport is keeping up with the generations coming through,” he says. “A lot of sporting administrators look three to four years out. But if you haven’t looked 20 years out, you’re in a completely new generation, one which may have no interest in your sport or product.”

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content