Is a company’s only responsibility to make profit per Nobel Prize winning economist Milton Friedman? AICD Senior Policy Adviser Lucas Ryan surveys the latest thinking.

In 1970, Milton Friedman wrote in a New York Times article that the only social responsibility of companies is to create profit. This idea, commonly called ‘shareholder primacy’, has dominated the structure and regulation of markets (including some interpretations of directors’ duties) since the industrial revolution.

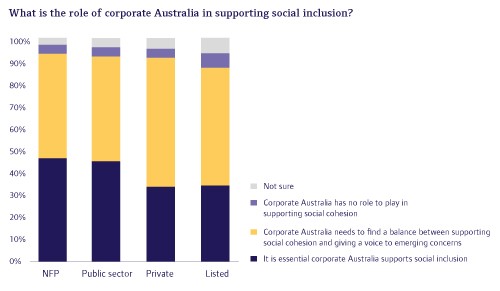

But sentiment is shifting. As a new survey of directors conducted jointly by the AICD and KPMG found, only three per cent of directors felt that corporate Australia had no role in supporting social inclusion, indicating that it is well accepted that business must play a part in addressing inequality. But the question of what role business should play has been left largely unanswered.

Among OECD countries, inequality is at its greatest in 30 years, not only in terms of wealth, but also education, employment, health, and the extent to which human rights are upheld.

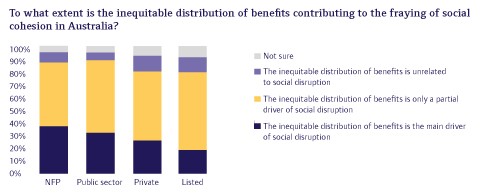

In our new research, 89 per cent of directors felt that the inequitable distribution of benefits contributed to fraying social cohesion (the ability of members of a society to cooperate in order to survive and prosper) in Australia.

Many now recognise the role of corporations in creating (or eroding) equality. This reflects a growing appreciation from business that extreme inequality harms economic growth, largely owing to its corrosive effect on the accumulation of human capital.

Companies appreciate this and are increasingly giving consideration to interests other than profit in assessing their performance. Ninety per cent of the ASX200 provide some level of reporting on environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors, demonstrating that such considerations are now firmly embedded in Australia’s corporate psyche.

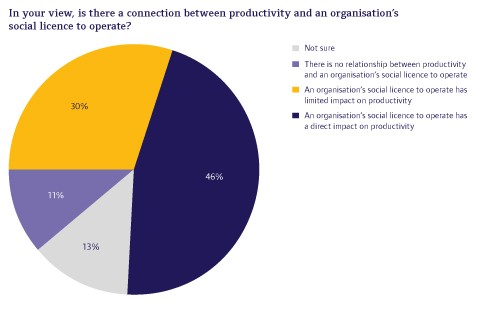

When the broader community bears the bulk of negative ESG impacts while investors reap the financial rewards, the imbalance is sometimes viewed through the prism of the ‘social licence to operate’ (SLO). SLO refers to the broad acceptance of a business’ operations by a community. Our study showed that 76 per cent of directors perceived a connection between an organisation’s productivity and its SLO, indicating that consideration of broader community interests are critical to business success.

However, these frameworks still interpret social and environmental considerations through the lens of their relationship to profit. For example, a farming company might prioritise environmental factors only to the extent that they could undermine operations or cause reputational damage. At the very least, it should be possible for directors to give reasonable weight to such factors in decision-making without considering them exclusively as they relate to profit. To do this, it must be possible to embed considerations such as SLO as part of a company’s purpose.

The ‘benefit corporation’ is an emerging incorporation model which seeks to address this imbalance by providing long-term mission alignment with value creation. They allow companies to raise capital and trade publicly while also providing a specific legal obligation for directors to consider mission-related factors in decision-making. Thirty-one American states already provide this incorporation type and interest in such structures is growing globally.

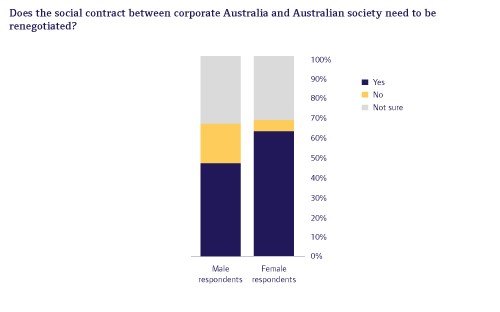

This interest reflects recognition among corporations, communities and legislators that there may be a need to re-think the implicit ‘social contract’ between business and the community. In our survey, we asked directors whether there was a need to renegotiate this ‘social contract’. Of all our questions, this received the most polarising results; from those rejecting that a social contract exists at all to those calling for its radical and immediate revision.

Half of directors felt that the social contract needed to be renegotiated and only 18 per cent disagreed. Interestingly, 30 per cent of respondents were ‘not sure’, indicating a need for a more inclusive debate about this issue and for the creation of a common language to establish a dialogue on the relationship between business and the community, and how it should be governed.

If boards are to set their sights on long-term value creation, it is necessary to consider whether profit as the primary purpose of a company provides the right foundation to do this, or whether it will ultimately hollow out longer-term sources of prosperity. Short-termism is cited as the scourge of good governance, but is it possible to truly focus on the long-term without considering, on some level, the community’s interest in and thereby acceptance of a corporation’s activity?

When considering what the right balance is for the purpose of a corporation, it is worth reflecting on what role we want business to play in our society, and to what extent the focus on maximising profit undermines equality and therefore long-term, sustainable economic growth. The purpose of business should be found in the answer to this question.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content