While directors may possess the skills and qualifications needed to govern, strong dynamics and relationships between board members make for a more effective board.

While it is now acknowledged boardroom culture matters, not much is understood about how boardroom culture defines and shapes the exercise of accountability in and around the boardroom. This understanding is vital to strengthening corporate governance.

Accountability for good governance is often viewed in the context of an outcome or a goal, a set of formal expectations that can be enshrined in mandates, codes or regulations depicting what should be done, by whom and how. The reality is very different.

The process of governing does not occur in a social vacuum.

This is the lived experience of non-executive directors (NEDs) who hold multiple directorships and report different experiences in how accountability is practised on different boards, even for similar tasks. These differences have their roots in director interactions, behaviours, routines and social norms unique to a given board.

Some boards are highly formal and procedural around debate, others are more engaged — with NEDs actively challenging each other and encouraging contention of ideas and proposals.

Differences in the social reality from board to board create an implicit understanding of the social order of things and can become self-regulating. The dynamic exerts subtle pressure for unity, determining what directors choose to do and say in exercising their influence, and how others’ opinions are responded to.

Such a nuanced view has been missing from the discourse about board accountability and effectiveness. Hard governance — the more formal instruments of accountability such as regulation, codes and mandates — while essential because it provides the boundary conditions for good governance to thrive, does not guarantee it. “Soft governance” does.

Soft governance — largely invisible (even to those in the boardroom), poorly understood and not given the attention it deserves — is the sum total of the shared history of interactions and ways of working: stated or unstated expectations and behavioural norms and routines of members.

The banking Royal Commission has highlighted egregious lapses in soft governance that all companies should heed.

As a psychologist, I have studied groups as complex social systems and have long been conscious of the “under-socialised view” of boards. This perspective sees the board group as one embedded in a complex web of relationships with unique power asymmetries and identity effects that can, at a subconscious level, influence the micro-behaviours of individual members.

My most recent research* reveals the sometimes chilling effects of a group dynamic on the contribution of individual NEDs.

The dilemmas of soft governance

The work of the director is complex. There are three dilemmas in particular all directors face, no matter how experienced they are:

- Informed but heedful This deals with the dilemma associated with information; the very real challenge of information asymmetry. How do I engage with management in a way that ensures I get all the information I need to make decisions, but at the same time retain a healthy scepticism and find other ways to verify and calibrate what I am told? It requires trusting as well as mistrusting what one is told.

- Challenging but supportive This deals with the dilemma associated with expertise. How do I use my expertise to ask questions to provoke the kind of thinking and questioning of assumptions I think is necessary, but still come across as supportive of management?

- Detached but involved This deals with the dilemma associated with role. As a NED, my relative distance from the day-to-day helps objectivity in what I see, which management, through their closeness to issues, may not be able to see. How do I achieve this without immersing myself in too much detail as a non-executive?

In theory, these dilemmas would be relatively easy to manage because corporate governance is based on the fundamental premise that trust and control are not mutually exclusive and that a NED can engage in both trust-based and control-based behaviours at the same time. The reality may be harder to achieve as NEDs possess a variety of tendencies or propensities that make them more predisposed one way or another. Skill alone, therefore, will not help directors navigate the dilemmas of soft governance.

Board capital as the source of a director’s identity

What a director brings in terms of background, experience, expertise and exposure is the source of their identity on the board, characterised as board capital. It is the sum of his or her human and social capital — a far broader notion than skill.

Human capital goes well beyond the sum of one’s sector or functional experience. Instead, it relates to experience working with diverse and alternative business models; experience working with the diverse strategies those business models imply; experience working with the assumptions underpinning those strategies; and experience working with the variety of consequences of actions taken as a result of those strategies. In effect, it relates to actual experience working with a diversity of mental models and schema. Cognitive psychologists call this “requisite variety”.

Social capital (unlike human capital) is not acquired via career experience forged in typical corporate governance circles, through professional networks or holding multiple directorships. Instead it extends to the diversity of social networks acquired through broader life experience across many domains: inter-generational, geography, education, socioeconomic status and ideology.

This kind of life experience and exposure gives NEDs better contextualisation skills especially at a time when the social licence of businesses is being closely scrutinised and the primacy of shareholder value challenged. Cognitive psychologists call this “external variety”.

Board capital is therefore a more holistic idea than the traditional notion of board skill. Importantly, how and where board capital is acquired matters and guards against the narrowing of the ideological perspectives and strategic horizons of the board when engaged in decision-making.

Additionally, the research shows that board capital is a proxy for influence because possession does not imply its use.

The power hierarchy and the proxy for influence

The research revealed a hidden power hierarchy, based on informal and subjective ranking of the board capital of individual NEDs. This self-construal of “place” in the hierarchy becomes an internalised guide for NEDs, determining if, when and how they will mount their influence attempts. It can determine the preparedness of a NED placed lower in the hierarchy to challenge during the process of shaping strategy.

Some may under-speak while others may dominate. When this occurs, independent-mindedness is lost and decision-making processes are compromised. This impacts the board’s effectiveness as the peak decision-making group.

However, directors are not just passive participants in the face of a power hierarchy. They don’t merely engage in mindless compliance with power structures. Instead they engage in conscious and deliberate attempts to gain approval, build rewarding relationships in the process and enhance self-esteem. That is to say each director makes, at the subconscious level, an internalised calculation of where they sit in this power structure, and the strength of their desire to earn peer respect and acceptance.

Self-censuring divergent views, silencing self-doubt or undertaking revisions of self-confidence may lead to unjustified support for the views of a powerful director — even when they hold a minority view. It may lead to higher-power directors subliminally discounting others’ contribution, rationalising away doubts or prematurely dismissing counter-positions.

These micro-behaviours are amplified by trust-based affiliations and allegiances within the board, reinforced along board capital lines, and may form subgroups with oversized influence. This is because it is part of the human condition that we tend to place a higher value on our own career experience and value the contribution of peers we judge as similar to us. NEDs who had been CEOs of listed companies previously were more likely to pay attention to those of similar backgrounds, while those who were retired partners of professional services firms tended to rate the experiences of NEDs of similar experience; both providing compelling rationales for doing so.

The critical role of director propensities

Both board capital and the willingness to use it are important in influencing high-stakes strategic decisions: the board capital to mount influence attempts successfully, and the willingness to mount them in the face of a self-regulating power dynamic that directors must sometimes push against.

It requires a lot of energy and personal courage to push against powerful individuals and coalitions, and relies on more than the possession of skills or board capital. It relies on propensities to help neutralise the adverse effects of power differentials. In particular, it requires both the propensity to influence and propensity to be influenced — and the character strengths these imply. Both these propensities, which imply courage, fortitude, humility and openness, must be in balance, especially when facing subtle pressure to conform to the majority opinion. If they are not in balance, independent-mindedness is compromised. Added to this is trust propensity — a generalised propensity to rely/depend on others and a faith in humanity, shaped early in one’s life.

The skills-based notion of boards is deeply flawed and ignores the underlying propensities of directors. Unlike skills, these are deeply wired and take considerable time to change. We can develop skills and strategies to help moderate our tendencies. However, it requires significant effort to recognise and reflect upon our tendencies that hold us back from being personally effective.

A typology of culture types

The chair plays a critical role in being alert to the effects of the power dynamic, ensuring that no one person or subgroup has an over-sized influence on deliberations and final decisions.

For a board, the primary consideration is to make collective sense of the challenges — to mobilise, direct and align management to face difficult and complex challenges, and collectively work to create the conditions for effective group functioning.

The real challenge facing chairs is how to facilitate agreement and disagreement. How do they allow robust debate and the proper contest of ideas to thrive, letting a debate run its course while maintaining the psychological safety required for all directors to feel secure enough to disagree with the chair and each other?

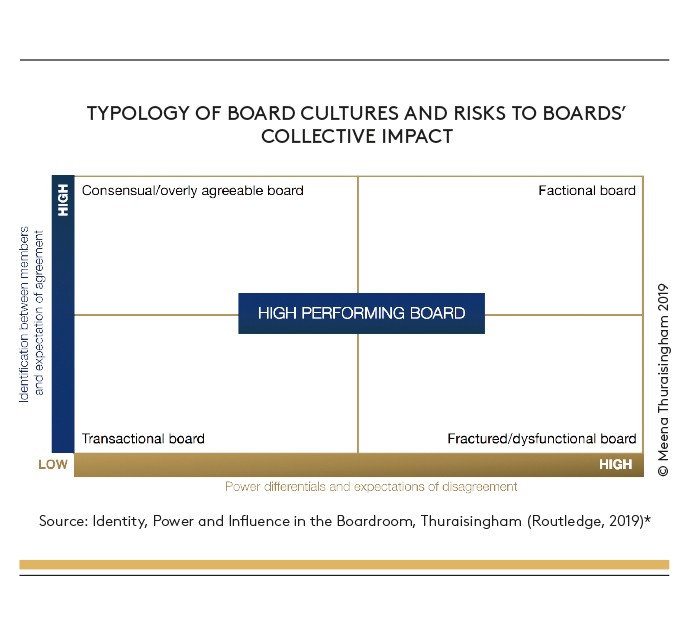

A typology of five culture types (moderated by the effects of power and identity) offers a chair the structure needed to focus their efforts on improving board culture and managing the associated risks (see graphic above).

A board is at its best when there is a healthy equilibrium between the effects of identity and power differentials. When members identify too strongly with each other, the contest of ideas and perspectives becomes less likely, groupthink emerges and an overly agreeable board develops. The reverse is also true, giving rise to a fractured board.

A productive tension between consensus and harmony on one hand, and dissent and discord on the other, keeps a board dynamic healthy. Directors need to cultivate a taste for both harmony and discord in order to be effective.

A word of caution: while typologies such as this one are useful, they don’t necessarily reflect the complexities in real life. For example, consensual boards can masquerade as high-functioning and efficient because decisions get through quickly with less time spent on robust debate. Similarly, factional boards can masquerade as high-functioning because decisions are carried quickly, usually by the loudest voices. An effective chair is alert to these social cues and the direction of travel of the dynamic. Adding just one NED can potentially alter a high-performing dynamic.

Implications for nominations committees

Nominations committees need to recognise the limitations of the traditional skill-based matrix, which has long been the guiding paradigm for selecting new directors. The underlying propensities of prospective NEDs also matter, and a more robust and systematic approach to identify and assess these is needed. A rethink is also needed to ensure an optimal mix of board capital for both consensus and contention to thrive on a board.

This applies equally with hiring retiring CEOs and executive directors as with hiring managing partners from professional services firms. Both can be biased by sector-accepted norms or industry recipes that may potentially trap thinking.

It will not guard against the unjustified support for a persuasive sub-group. Some boards may fail a rigorous test of the extent of their cognitive and ideological diversity, but it is not too late to consider a different paradigm from the skill-based board to guide future board renewal efforts.

There is evidence of board evaluations/reviews being limited in strengthening board decision culture. This is because they tend to focus on how the formal instruments of control are operating rather than recognising the social control the behaviour of powerful individuals can have. Greater awareness and alertness to the human dimension of governance is required of boards.

Nominations committees might consider these questions:

- How can boards ensure there is sufficient cognitive and ideological diversity applied to how value-creating decisions are collectively influenced?

- How can boards assess if NEDs’ use of board capital is being enabled or hindered by power asymmetries?

- What and how are NEDs’ propensities taken into account in director selection and development to allow both consensus and contention to thrive in equal measure, and the implicit signals it sends the wider organisation it governs about the culture it expects?

- How systematically is the propensity to influence and the propensity to be influenced assessed during the appointing process?

- To what extent does your board effectiveness review surface and address the undercurrents that impede independent-mindedness?

Soft governance offers great promise in helping boards face the silent risks it carries and actively reshape the dynamics hindering their effectiveness.

Meena Thuraisingham GAICD is founder/principal at BoardQ advisory. Former executive roles include ANZ and Esso Australia. She recently completed her PhD at RMIT on the antecedents and moderators of board decision dynamic. She is a member of the International Women’s Forum.

*This research was based on 15 ASX-listed companies spread across sectors at the top end of the listing. The study used post-event NED recollections in the 12 months preceding the finalisation of a transformative decision. In all cases, this related to entry into a new market by acquisition, a high-stakes decision for the company and NEDs. The focus on large value-creating decisions amplified the test board effectiveness was put through. Using NEDs as “expert witnesses”, (applying a range of methodologies including sense-making theory, narrative analysis and semi-structured behavioural interviewing) the research focused on NEDs’ influence attempts when shaping strategy, the thinking behind those attempts and their responses to the influence attempts of their peers.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content