The focus this week was on RBA Governor Philip Lowe’s speech on unconventional monetary policy, which has encouraged some forecasters to tip the arrival of a terminal cash rate of 0.25 per cent and QE next year.

Local data on construction and capital expenditure were relatively weak. A significant gap has emerged between international institutions’ pessimism about the global outlook and market optimism in the form of the so-called reflation trade.

World trade flows fell in September. This week’s readings include a deep dive on the Australian labour market, a look at Australia’s national fiscal outlook, the return of fiscal activism to the UK, and Martin Wolf’s pick of the best economics books of the year.

Finally, a very early plug for next year's webinar on what 2020 will bring for the global and Australian economies.

What I have been following in Australia…

What happened:

RBA Governor Philip Lowe gave a much anticipated speech (broadcast live on the central bank’s web site) on unconventional monetary policy.

Drawing on the lessons from a BIS report on unconventional monetary policy tools (or what the report calls UMPTs), the first part of the speech discussed negative interest rates, extended liquidity operations, quantitative easing (QE) and forward guidance and argued that (i) there was strong evidence that liquidity support measures and targeted interventions helped stabilise markets and financial systems, but that the evidence for other measures was less compelling; (ii) that UMPTs have had some unwelcome side-effects including risks to bank profitability and financial stability, a possible blurring of the lines between fiscal and monetary policy, and – in another message to Canberra – the possibility that ‘the willingness of a central bank to use its full range of policy instruments might create an inaction bias by other policymakers, either the prudential regulators or the fiscal authorities…it could lead to an over-reliance on monetary policy;’ and (iii) a package of measures works best, supported by clear central bank communication.

Most attention was on the governor’s discussion of the implications of all of this for Australia. Here, Lowe made five key points:

- ‘Australia's financial markets are operating normally and our financial institutions are able to access funding on reasonable terms…So there is no need to change our normal market operations to do anything unconventional here.’

- In his view, ‘negative interest rates in Australia are extraordinarily unlikely…having examined the international evidence, it is not clear that the experience with negative interest rates has been a success.’

- The RBA has ‘no appetite to undertake outright purchases of private sector assets as part of a QE program…While there are some scenarios where such intervention might be considered, those scenarios are not on our radar screen.’

- Instead, ‘if – and it is important to emphasise the word if – the Reserve Bank were to undertake a program of quantitative easing, we would purchase government bonds, and we would do so in the secondary market… Our current thinking is that QE becomes an option to be considered at a cash rate of 0.25 per cent, but not before that.'

- The ‘threshold for undertaking QE in Australia has not been reached, and I don't expect it to be reached in the near future…QE would be considered if there were an accumulation of evidence that, over the medium term, we were unlikely to achieve our objectives. In particular, if we were moving away from, rather than towards, our goals for both full employment and inflation, the purchase of government securities would be on the agenda of the Board.’

Lowe concluded by reminding his audience that the RBA continues to be cautiously optimistic on the outlook, as its ‘central scenario for the Australian economy remains for economic growth to pick up from here, to reach around 3 per cent in 2021. This pick-up in growth should see a reduction in the unemployment rate and a lift in inflation… There may come a point where QE could help promote our collective welfare, but we are not at that point and I don't expect us to get there.’

Why it matters:

With the cash rate already at a record low of 0.75 per cent and the RBA’s latest forecasts indicating that the central bank thinks that inflation is set to remain below the bottom of its target band past the end of 2021, there had been growing speculation that the RBA could embark upon a program of QE next year. So, this week’s speech was a chance for Governor Lowe to clarify the central bank’s position.

In fact, a fair bit of what Lowe said had already been communicated by the RBA. For example, back in October the governor said that he thought negative interest rates were ‘extraordinarily unlikely’ – a comment he repeated this week. And in September, as part of an extended written response to parliamentary questions, the RBA indicated that the most likely unconventional policy option it would pursue ‘would involve reducing the cash rate to a very low level and possibly purchasing government securities to lower the risk-free rate further out along the term spectrum’. Again, that’s consistent with the observation in Lowe’s speech that if the central bank did decide to undertake QE, it would do so by purchasing government bonds.

One interesting new piece of information we did learn this week is that the RBA considers 0.25 per cent as the effective lower bound (ELB) for the cash rate. That’s because at a cash rate of 0.25 per cent, the interest rate paid on surplus balances at the RBA would already be at zero given the corridor system it operates. That change means that markets no longer see a cash rate of 0.5 per cent as the end point of the RBA’s current easing cycle.

What did the speech do to expectations around the probability of the RBA adopting unconventional monetary policies? Governor Lowe was at pains to point out – repeatedly – that he thought the adoption of QE was very unlikely. But many market participants seem to have judged that, by talking in detail about its likely approach to unconventional policy, the RBA has signalled that QE is now a realistic prospect, and share and bond markets appear to have reacted accordingly. This is all a bit reminiscent of the Far Side cartoon on what dogs hear: the governor may well have been working hard at setting out a long list of qualifications and cautions around the possibility of QE, but decent share of the intended audience heard ‘QE’ and not much else.

The speech did provide some clear guidance as to the circumstances under which the RBA would feel QE would be appropriate: if it were to find itself ‘moving away from, rather than towards’ its goals for full employment and inflation, a declaration will keep attention firmly focussed on monthly labour market outcomes over the coming months.

Three final thoughts on this, all drawing on the BIS report referenced in Lowe’s speech.

First, the report is careful to distinguish between two situations in which a central bank might seek to deploy UMPTs. The first of these is when there have been disruptions in the monetary policy transmission chai. The second case is when it is necessary to provide additional stimulus once the conventional policy rate is constrained by the ELB. Only the second case applies to current Australian circumstances (well, almost applies, as there are still 50 bp of easing to go before we hit the ELB).

Second, the BIS review emphasises that there could be positive benefits from a central bank ‘demonstrating the ability to act swiftly and decisively’ when deploying UMPTs. It does say that this is particularly the case in the circumstance of disruption to the policy transmission chain, but also notes that it could apply in the case when the ELB becomes a constraint. That suggests that, despite the clear caution signalled by the speech, if the RBA did decide it needed to move on QE, the policy intervention could roll out quite quickly.

Finally, the report also includes an interesting discussion of the policy challenge faced by small open economies such as Sweden and Switzerland when QE in larger economies spilled over into large exchange rate appreciations, prompting both central banks to target a weaker exchange rate (including in the case of the SNB, via direct foreign exchange market intervention). In recent months, the RBA has made it plain both that it considers the exchange rate channel important for monetary policy transmission and that it sees the impact of other central bank moves to ease policy as an important constraint on its own choices because of the potential fallout via a stronger dollar.

What happened:

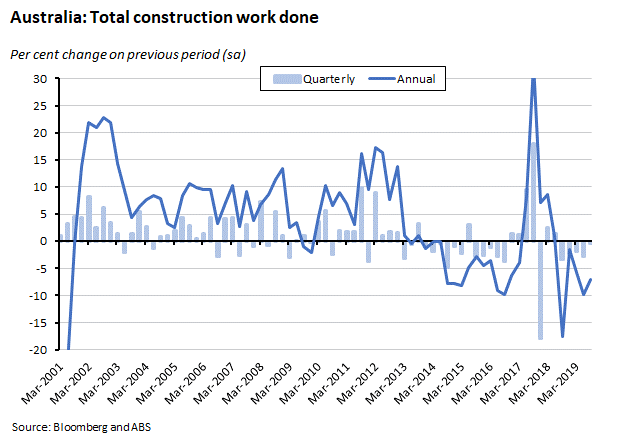

According to the ABS, the value of total construction work done fell 0.4 per cent (chain volumes, seasonally adjusted) in the September quarter, and was down seven per cent over the year. By component, building work done fell 0.5 per cent over the quarter and 5.1 per cent over the year while engineering work done was down 0.2 per cent over the quarter and 9.6 per cent over the year.

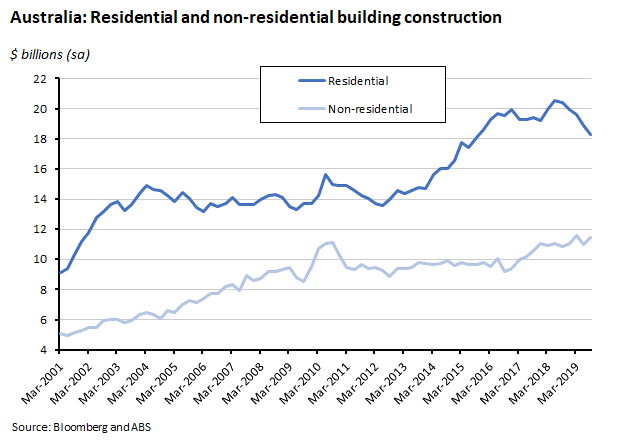

Residential construction fell 3.1 per cent over the quarter and 10.6 per cent over the year, while non-residential construction rose four per cent in quarterly terms and 5.3 per cent in annual terms.

Why it matters:

The consensus had been for a one per cent quarterly drop in total construction work done, so the actual outcome was a bit better than expectations. That said, work done has now fallen for five consecutive quarters. That weakness is mainly a story of residential construction, while non-residential construction has continued to expand.

What happened:

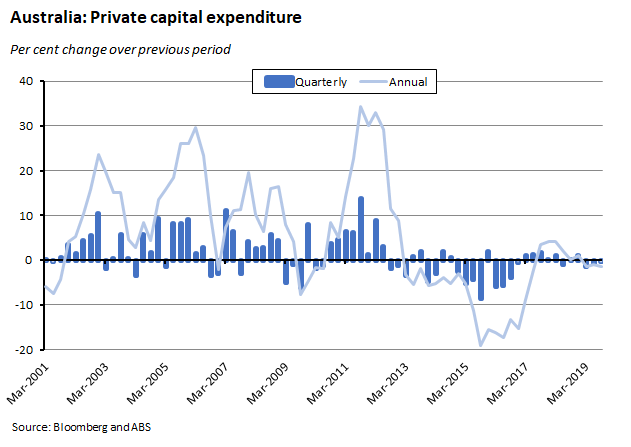

The ABS reported that private new capital expenditure in the September quarter fell 0.2 per cent over the quarter (seasonally adjusted) and was down 1.3 per cent over the year. Expenditures on building and structures rose 2.7 per cent in quarterly terms but were still down 0.3 per cent over the year, while spending on equipment, plant and machinery fell 3.5 per cent over the quarter and 2.4 per cent over the year.

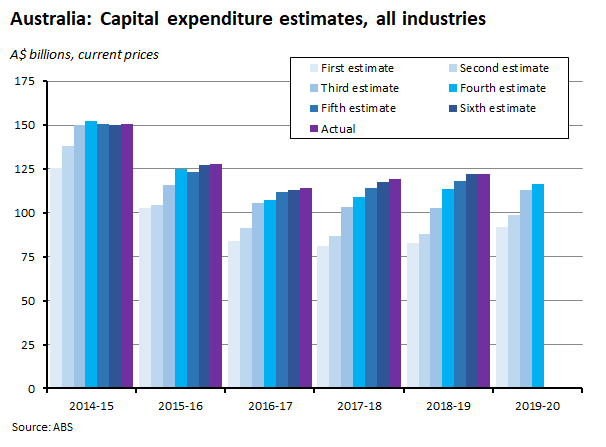

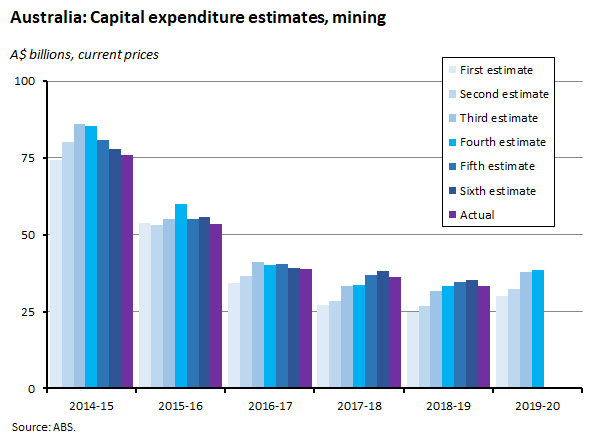

The same release also reported the fourth estimate for total capital expenditure for 2019-20. At $116.7 billion, this was up 3.4 per cent on the third estimate and was 2.5 per cent higher than the corresponding estimate for 2018-19.

By sector, the estimate for mining was 15.7 per cent higher than its 2018-19 counterpart, while manufacturing was up just one per cent.

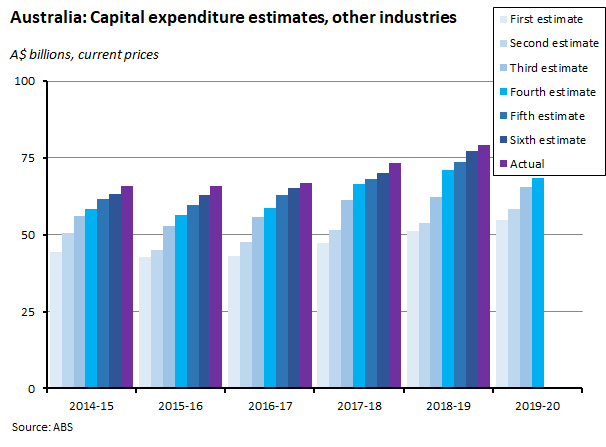

The fourth estimate for other industries was 3.3 per cent lower than the 2018-19 estimate.

Why it matters:

The modest fall in capital expenditure in the September quarter was a little bit weaker than market expectations of no change and is consistent with the continuing story of weak investment this year, reflecting the combination of high levels of global economic policy uncertainty and subdued domestic activity.

Disappointingly, the fourth estimate for capital spending in 2019-20 was also soft (the 2.5 per cent rise over the 2018-19 estimate is down quite sharply from the 10.7 per cent increase that the June quarter’s estimate three reported relative to the corresponding 2018-19 outcome). By sector, intentions for mining capex continue to look relatively robust, if softer relative to last quarter, but spending intentions for manufacturing have weakened quite a bit while investment for other selected industries is now lower than it was at the time of the corresponding estimate last year.

. . . and what I’ve been following in the global economy

What happened:

Last week, the OECD released its November 2019 economic outlook. The OECD estimates that the global economy grew by just 2.9 per cent this year, the weakest outcome since the GFC. It reckons that there are ‘increasing signs that the cyclical downturn is becoming entrenched’ and thinks that world growth will remain unchanged at 2.9 per cent next year and only manage to edge up to three per cent in 2021, weighed down by high policy uncertainty and weak trade and investment. The forecast also cautions that actual outcomes could be even worse, with downside risks around trade and investment protectionism, continued Brexit uncertainty, a sharper-than-expected downturn in China, and dangers around high levels of corporate debt and declining credit quality.

The OECD warns that ‘the mix between monetary and fiscal policies is unbalanced’ across the world economy, contrasting decisive and timely central bank easing with what it sees as only ‘marginally supportive’ fiscal policy. But it’s even more concerned about what it sees as an ongoing failure on the part of governments to address the implications of several structural shifts including climate change, digitalisation, trade and geopolitics.

All that said, the organisation does forecast a modest improvement in Australia’s growth outlook, with GDP expected to accelerate from an anaemic 1.7 per cent this year to 2.3 per cent next year. It doesn’t think that will be enough to bring down unemployment or return inflation to target however, and therefore predicts further monetary easing while suggesting that ‘a more expansionary fiscal stance may be warranted’ in the form of more public investment in ‘green infrastructure’ and bringing forward shove-ready projects from the government’s Infrastructure Investment Program. It also repeats its accustomed policy prescription that Canberra should make the tax system more growth-friendly by shifting the tax mix away from direct taxes and inefficient measures like stamp duty to the GST and land taxation.

Why it matters:

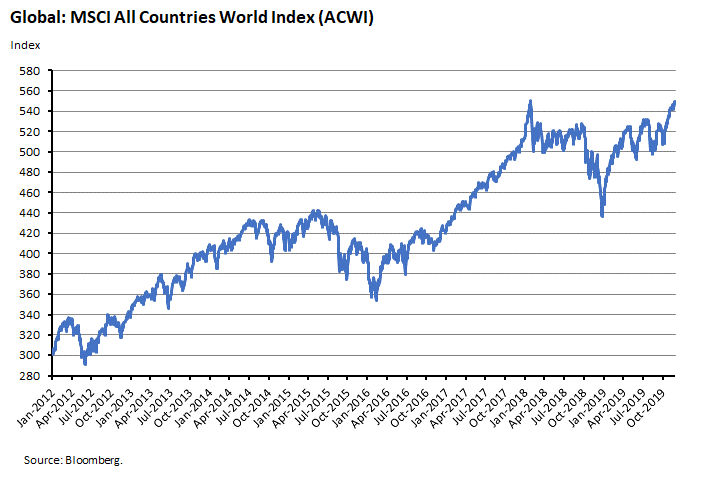

The OECD’s downbeat outlook for the world economy stands in stark contrast to the bullish tone take by financial markets which has seen US and Australian share markets reach new record highs in the past few weeks and the global MSCI rise to close to its January 2018 high.

What’s going on? Market optimism seems to be driven by three main factors.

- First and most important, central banks led by the US Fed have now delivered some significant monetary policy stimulus. Back at the end of 2018, the Fed was still indicating that it was planning to impose a further 75bp of rate hikes this year. Instead, Jay Powell has delivered three 25bp rate cuts, moving at its July, September and October meetings. At the same time, the European Central Bank has also loosened policy, pushing its interest rate further into negative territory with its first cut since 2016 in September and announcing the resumption of bond purchases. China’s PBOC has also got in on the action, earlier this month cutting the interest rate on its one-year medium-term lending facility for the first time since early 2016.

- Next, and almost as important, markets have become more optimistic about the outlook for the US-China trade and technology conflict. Washington and Beijing resumed trade talks in September and in October the two sides announced that they had reached tentative agreement on a ‘phase one’ deal that would halt the escalation in tariffs and potentially allow some unwinding of the protectionist measures that have already been imposed.

- Markets have also become more optimistic about Brexit risk, reckoning that the chance of the UK leaving the EU without a deal have fallen significantly since PM Boris Johnson negotiated his revised agreement with Brussels.

That combination of central bank stimulus plus a reduction in fears around two of the biggest sources of global economic policy uncertainty have together helped power a so-called reflation trade that has buoyed market performance in recent weeks. That optimism may turn out to be the right bet if the stimulus gains traction and there is no renewed spike in uncertainty. But the contrast with the OECD’s (and the IMF’s before that) much bleaker assessment of current conditions serves as a warning that any rebound for the global economy next year is still far from a done deal (see below).

What happened:

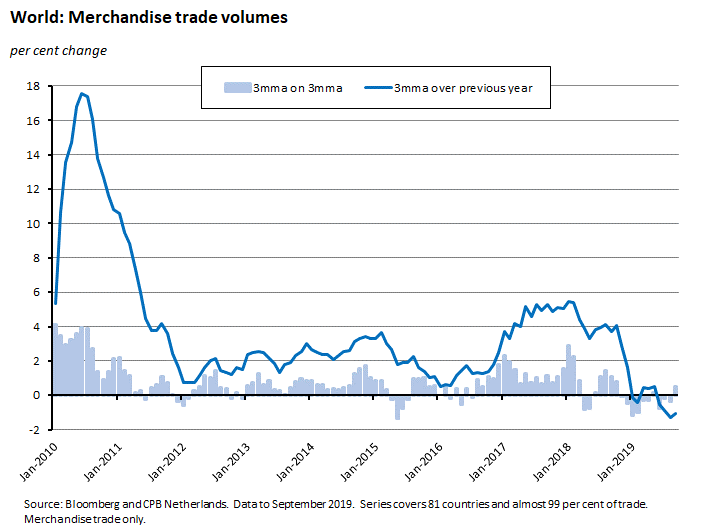

According to the latest issue of the world trade monitor, the volume of world trade fell 1.3 per cent in September, after having increased 0.5 per cent the previous month. World trade momentum (measured as the average of the current three months over the average of the previous three months) edged up to 0.5 per cent, recording its first positive result since May this year, but in annual terms trend growth remained stuck firmly in negative territory.

Why it matters:

World trade has played a central role in stories about the global economy this year, in large part because of the concerns over the US-China trade and technology conflict and its impact on trade, manufacturing, investment and business confidence. As noted in the previous story, since early October the prospect of a ceasefire in the standoff between Washington and Beijing in the form of a so-called ‘phase one’ trade deal has been boosting market optimism. That optimism had also received some limited support in the data in the form of two consecutive monthly increases in trade volumes in July and August. September’s fall is a useful reminder that it’s still far too early to call any kind of sustained turnaround in trade flows, especially given that, for now, the US plan to impose a new 15 per cent tariff on US$156 billion of Chinese imports with effect from 15 December is still in place and the phase one trade deal is yet to be delivered.

What I’ve been reading: articles and essays

RBA Deputy Governor Guy Debelle spoke on employment and wages, contrasting the fairly rapid rate of employment growth (an annual pace of 2.5 per cent for much of the past three years) with a relatively stable unemployment rate and a marked decline in the pace of wage growth that started around 2012. One familiar part of the story is a rise in labour supply in line with labour demand, reflected in a participation rate that has reached record highs. That shift in participation rates has been driven by female employment growth (which alone accounts for two-thirds of total employment growth over the past year, with female participation at its highest rate, and the gap between female and male participation its lowest ever) and a rise in the participation rate of older Australians (the share of 55 year olds and over that are employed has risen from 22 per cent to 35 per cent over the past two decades). Possible explanations for the former development include trends in child care costs and the increase in the level of mortgage debt and for latter include improving health, changes in pension age, and rising indebtedness. Meanwhile, the decline in the pace of wage growth has been accompanied by a sharp fall in the share of jobs receiving ‘large’ (greater than four per cent) wage rises and a shift to a norm of wage increases in the two per cent range – perhaps reflecting the success of the RBA’s two-three per cent inflation target in anchoring both inflation and wage expectations – along with declines in the share of workers receiving a promotion in existing jobs or switching to other jobs. Debelle concludes his assessment of labour market conditions by restating the judgment included in November’s Statement on Monetary Policy: wage growth is likely to ‘remain largely unchanged at its current level over the next couple of years.’ That expectation is underpinned by the observation that around 80 per cent of firms have told the central bank that they expect stable wage growth in the year ahead compared to only 10 per cent who report expecting stronger growth.

UNSW’s Richard Holden argues that Australia’s relative economic success is the product of ‘staunchly centrist economic policies’ that have ‘combined the virtues of markets with a strong social safely net’ but worries that the current state of the economy might test the nation’s commitment to the policy centre ground.

Monash’s Isaac Gross reviews some lessons from the RBA’s macro model for the possible implications of Quantitative Easing.

The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) has produced a helpful graphical summary of the 2019-20 national fiscal outlook.5 There’s also a more detailed document (pdf) available. The analysis brings together Commonwealth, State and territory and local government accounts to provide a picture of the overall national budget position. The PBO reports a stronger national budget position, with the national net operating balance forecast to reach a surplus of more than $20 billion in 2018-19, or 1.1 per cent of GDP.6 That surplus is the first in more than a decade and is forecast to grow to $42.5 billion or two per cent of GDP by 2022-23 (the end of the 2019-20 forward estimates period), mainly due to restrained expenditure growth across all levels of government. National net infrastructure investment is forecast to peak at $37.9 billion in 2019-20 due to large investment programs in New South Wales and Victoria. That’s a record in dollar terms and as a share of GDP is close to the peak recorded during the GFC stimulus period. National net debt as a share of GDP is projected to peak in 2019-20 at 22.1 per cent of GDP before falling to 20.3 per cent by 2022-23.

Mark Ashworth ponders the implications for the Bank of England of the return of fiscal activism to the UK, regardless of who wins December’s election.

A couple of interesting takes on the polity that is the United States. This piece in the WSJ describes how brands are increasingly caught up in the rise of political partisanship: Democrats wear Levis and Republicans wear Wranglers, apparently. And Joel Kotkin thinks he sees an America that is drifting towards Feudalism.

Last month, Mervyn King delivered the 2019 Per Jacobbson Lecture. King’s theme was that in the aftermath of the Great Depression and the collapse of the Bretton Woods system the world experienced periods of political and intellectual turmoil, but that while the current period has again delivered political turmoil, there has been no comparable rethinking of the basics of economic policy. King reckons that we are now deep in a Great Stagnation in the form of a low growth trap characterised by radical uncertainty (that depresses investment spending) and misallocation of resources (too much investment in the Chinese and German export sectors and in some advanced economy commercial property sectors, too little in infrastructure). He also worries about the level of preparation for the next financial crisis.

Nouriel Roubini warns that the current bout of global financial market exuberance fails to take into account that some fundamental risks are getting worse, not better.

The IMF has published the latest issue of its Finance & Development magazine, where the main theme is the economics of climate and includes an interesting piece on financial risk. The same issue also includes a nice profile of urban economist Edward Glaeser, sometimes described (including here) as ‘the leading thinker about the economics of place,’ who argues that excessive regulation acts as a tax on development and who is sceptical of historic preservation rules.

The FT has a Big Read on China’s reversal in policy towards renewables and the consequent sharp drop in Chinese investment into clean energy, as Beijing presides over an economy that has more wind and solar power than any other economy but is also the world’s biggest builder of new coal plants.

Also from the FT, Martin Wolf’s selection of the Best books of 2019: Economics. The only one of these I’ve read this year is the Giridharadas (although it hasn’t made it to a review here yet, sorry). I’ve linked to reviews and discussions of the Milanovic, Philippon and Blustein books, and hopefully I’ll be getting either one of them or the Acemoglu and Robinson book for Christmas to set me up for some summer reading!

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content