The international banking turmoil that afflicted the US and Swiss financial sectors last month has taken a toll on the global outlook. According to the latest economic assessment from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the evidence of institutional fragility due to higher interest rates and the consequent tightening in global financial conditions mean that the world economy is now at increased risk of a hard landing. In addition, the IMF is also sounding glum about medium-term prospects for global growth.

The IMF has also cut its forecast for Australian economic growth this year to 1.6 per cent, down from its October 2022 forecast for 1.9 per cent growth.

While there are storm clouds on the international horizon, however, the recent economic news has been more positive closer to home. The Australian economy added another 53,000 jobs last month and the unemployment rate remains at a near half-century low. Household sentiment has been boosted by the RBA’s 4 April decision to pause in its rate hiking cycle, although confidence remains at very subdued levels by historical standards. And the latest NAB monthly survey confirmed that business conditions continue to be robust even as cost pressures are showing signs of moderating, albeit the latter are still running well-above pre-pandemic rates. Indeed, the latest set of data are arguably strong enough that the RBA might be at least slightly tempted to deliver another 25bp rate increase next month, although the upcoming release of the quarterly consumer price index on 26 April remains a critical factor for that decision.

The IMF is worried about financial stress and global growth

According to the April 2023 IMF World Economic Outlook (WEO), the global economy is – yet again – facing another ‘highly uncertain moment’. Earlier this year, when it published the January 2023 WEO update, the IMF had allowed a modest note of optimism to creep into its hitherto overwhelmingly gloomy pandemic-era economic commentary. Granted, back then the Fund still thought that ‘the balance of risks to the global outlook remains tilted to the downside’, but it also reckoned that ‘adverse risks have moderated’ after this year got off to a better-than-expected start as Europe avoided a forecast recession and Beijing exited from its zero-COVID policy. Unfortunately, last month’s jump in financial market volatility means that in the latest edition of the WEO the pendulum has swung back to the pessimism that has become a hallmark of recent Fund analysis.

The IMF’s current worry is the way in which rapid increases in global interest rates plus an anticipated slowing of economic activity have interacted with supervisory and regulatory gaps and a series of bank-specific risks. This combination has punished financial institutions with business models that were heavily reliant on low interest rates, resulting in the failure of three regional US banks. That in turn triggered market concerns that culminated in the regulator-driven takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS. According to the Fund, the subsequent increase in financial market stress means that:

‘…the fog around the world economic outlook has thickened…and the balance of risk has shifted firmly to the downside so long as the financial sector remains unsettled…A hard landing – particularly for advanced economies – has become a much larger risk.’

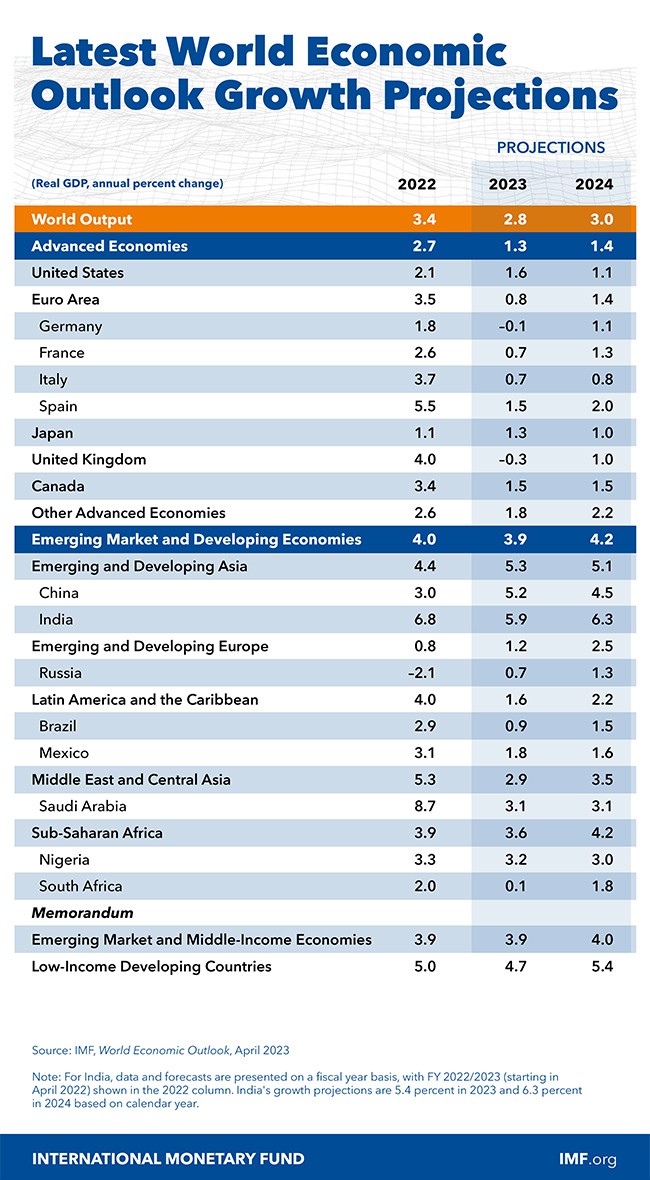

In fact, the IMF’s baseline forecast for the world economy hasn’t changed that much. Its new forecast is for global output growth to fall from an estimated 3.4 per cent rate last year to 2.8 per cent this year (just 0.1 percentage points weaker than it had forecast in January 2023) and then rise to three per cent in 2024 (another 0.1 percentage point downgrade from January’s prediction). Note that those are very weak growth rates. By way of comparison, during the two pre-pandemic decades, annual global growth averaged 3.9 per cent (2000-09) and 3.7 per cent (2010-19).

This week on The Dismal Science podcast, we cover the latest set of strong jobs numbers, a surge in consumer confidence, the IMF's outlook for global growth and the lack of housing supply.

What has changed is the risks around the IMF’s projections. For example, in what it calls a ‘plausible alternative scenario’ the Fund considers the likely impact of a moderate additional tightening in credit conditions due to further episodes of banking stress. It thinks this would see global growth this year slip even further, dropping to a meagre 2.5 per cent.

As if that wasn’t grim enough, the IMF also judges that threats to this outlook are ‘squarely to the downside’ with ‘a significant risk that the recent banking system turbulence will result in a sharper and more persistent tightening of global financial conditions’ than in either the baseline or the plausible alternative scenario. As a result, it now reckons that the probability of global growth falling below two per cent this year – something that has happened just five times (in 1973, 1981, 1982, 2009 and 2020) since 1970 – is now about 25 per cent, or more than double the normal probability. The IMF’s forecasts also put the risk of an outright contraction in global real GDP per capita this year at about 15 per cent.

Downside risks to the near-term outlook highlighted in this month’s WEO include: the possibility of bigger-than-expected contractionary effects from already-delivered interest rate hikes; the prospect of global inflation proving to be stickier than expected and therefore requiring a further dose of monetary policy tightening; the danger of a faltering in China’s post-COVID recovery; the threat of an escalation of the war in Ukraine; and the potential for the negative consequences of geo-economic fragmentation to be larger than anticipated.

Set against that long list of concerns, on the upside the IMF does admit the possibility that the world economy could again prove to be more resilient than expected, as turned out to be the case in 2022.

The Fund’s gloom also extends to the medium term

The IMF is not just unhappy with the short-term outlook. Over the medium term, the Fund thinks that ‘the prospects for growth now seem dimmer than in decades.’ The IMF does not see much scope for the world economy to return to pre-pandemic growth rates in coming years, citing an unhelpful combination of a slowdown in the pace of catch-up growth in the dynamic East Asian economies from China to Korea, slower growth in the global labour force, intensified headwinds from geo-economic fragmentation (including the impact of Brexit, ongoing US-China trade disputes, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine), and a downturn in the expected pace of supply-enhancing reforms.

All up, not much of a ‘Happy Easter’ from the world’s leading international economic institution.

What happened on the Australian data front this week?

Meanwhile, Australia’s remarkable period of labour market resilience continued through last month, despite the global economic and financial concerns discussed above. The ABS said that employment in Australia rose by around 53,000 people (seasonally adjusted) in March 2023, comfortably exceeding the consensus forecast for a 20,000 rise. Full-time employment rose by 72,200, more than offsetting a 19,200 decline in the number of the part-time employed. The employment to population ratio edged up to 64.4 per cent while the participation rate was unchanged at 66.7 per cent. That means both ratios were just 0.1 percentage points below their recent November 2022 record highs of 64.5 per cent and 66.8 per cent, respectively.

According to the Bureau, the number of unemployed people fell by 1,600 in March, and the unemployment rate remained unchanged at 3.5 per cent. Again, that outperformed the median market forecast, which had anticipated a slight increase in joblessness in the form of a 3.6 per cent unemployment rate. The underemployment rate, however, did increase, rising by 0.4 percentage points from 5.8 per cent in February to 6.2 per cent in March. As a result, the underutilisation rate also rose by 0.4 percentage points to 9.7 per cent but remains more than four percentage points lower than its pre-pandemic level in March 2020.

The ABS said that there were 600,710 short-term visitor arrivals (measured by the number of international border crossings) in February 2023, up more than 510,000 on the same month last year. There were 1,375,520 arrivals in total, up more than 1,100,000 in annual terms. The same data show there were 142,580 international student arrivals this February. That was an increase of 93,270 over February 2022 but still 22.5 per cent below pre-COVID levels as recorded in February 2021.

The Westpac-Melbourne Institute monthly Consumer Sentiment Index (pdf) jumped by 9.4 per cent in April 2023 to an index reading of 85.8, propelling confidence to its highest level since June 2022. Unsurprisingly, Westpac attributed the lift to the RBA’s decision to pause in the rate hiking cycle at its 4 April meeting (the survey underpinning the April index was conducted between April 3 – 6), noting that confidence amongst respondents with a mortgage soared by 12.4 per cent over the month. Despite April’s lift in sentiment, however, in absolute terms confidence remains weak and is still more than ten per cent below its level in April 2022, the month before the RBA started to increase the cash rate. Likewise, confidence amongst respondents with a mortgage is still 14.5 per cent below the level prevailing before the start of current the monetary policy tightening cycle. The Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index of Unemployment Expectations fell 3.3 per cent in April, indicating that consumers feel more positive about the labour market this month.

Consistent with headline monthly figures, the ANZ-Roy Morgan weekly Index of Consumer Confidence also increased last week in response to the RBA’s decision to leave the cash rate on hold, in what ANZ said was the most positive result following an RBA meeting since before the current rate hike cycle commenced in May 2022. The overall confidence index rose 1.1 points to an index reading of 79.3 last week, with the gain powered by a 3.9-point increase in confidence for those paying off their mortgage. This also marked the first time that confidence had increased for three consecutive weeks since last November. Even so, the reported level of confidence remains very low, and has now been stuck below 80 for a sixth consecutive week. The accompanying weekly measure of household inflation expectations fell by 0.6 percentage points to 5.1 per cent, which is the lowest reading since mid-February.

The NAB Business Survey for March 2023 reported that business conditions slipped lower last month by two index points but that still left them recording a still-strong index reading of +16 points, well above the series’ long-run average. Respondents said that trading conditions remain healthy with businesses continuing to benefit from strong demand across most states and sectors. Business confidence improved in March, with the index rising three points, although this indicator remains below its average at -1 index point. NAB also reported that price and cost pressures showed some signs of easing last month, with growth in labour costs slowing from 2.6 per cent in February to 1.9 per cent in March (albeit still well-above the pre-COVID average of 1.1 per cent) and growth in purchase costs falling from three per cent to 1.8 per cent over the same period (again, with the latter remaining above the pre-COVID average of 0.9 per cent). The pace of overall price growth also slowed. (All price and cost numbers in quarterly equivalent terms).

The ABS said that its experimental indicator of monthly business turnover rose over the month in nine of the 13 published industries in February 2023 (seasonally adjusted) and was higher in annual terms across all 13. The construction sector enjoyed the largest monthly increase, with turnover up by 4.6 per cent to stand 15.4 per cent higher than in February 2022 – the highest level since the turnover series began in January 2010. The Bureau pointing to a large pipeline of infrastructure projects as supporting industry activity. The largest fall in monthly turnover was suffered by the mining industry, which the ABS related to a decline in iron ore exports and a drop in global lithium prices.

Another ABS experimental measure, the monthly household spending indicator, rose 11.8 per cent over the year in February 2023 on a current price, calendar-adjusted basis. That was the slowest rate of growth in annual spending since March 2022 with the rate of increase in discretionary spending slowing to just 5.8 per cent, the softest performance since last January. In contrast, non-discretionary spending was up 17.5 per cent, reflecting increased expenditure on transport and food. Through the year spending was up on both services (17.6 per cent) and goods (6.1 per cent).

Total dwelling commencements fell 6.7 per cent over the quarter in December 2022 (seasonally adjusted) to be down 21.9 per cent over the year. According to the ABS, new private sector house commencements fell 2.3 per cent quarter-on-quarter and dropped 15.3 per cent year-on-year while new private sector other residential commencements slumped 16.5 per cent in quarterly terms and tumbled 34.2 per cent over the year.

Finally, noted from last week: the ABS said that Australia recorded a $13.9 billion trade surplus in February this year, up $2.6 billion on the January 2023 result, and the Bureau also reported that the number of payroll jobs rose 0.6 per cent over the month to mid-March 2023. The total number of payroll jobs is now 10.5 per cent higher than pre-pandemic levels although two industries (Manufacturing, down 0.3 per cent and Transport, postal and warehousing, down 0.9 per cent) had fewer jobs.

Other things to note . . .

Last week’s April 2023 Financial Stability Review from the RBA said that although global financial stability risks had increased following a sequence of bank failures, the Australian financial system remained strong, stating that ‘Australian banks are well regulated, well capitalised, profitable and highly liquid’. It also warned that a small cohort of borrowers were at increasing risk of financial stress due to rising interest rates and high inflation, although it emphasised that most Australian households remained resilient.

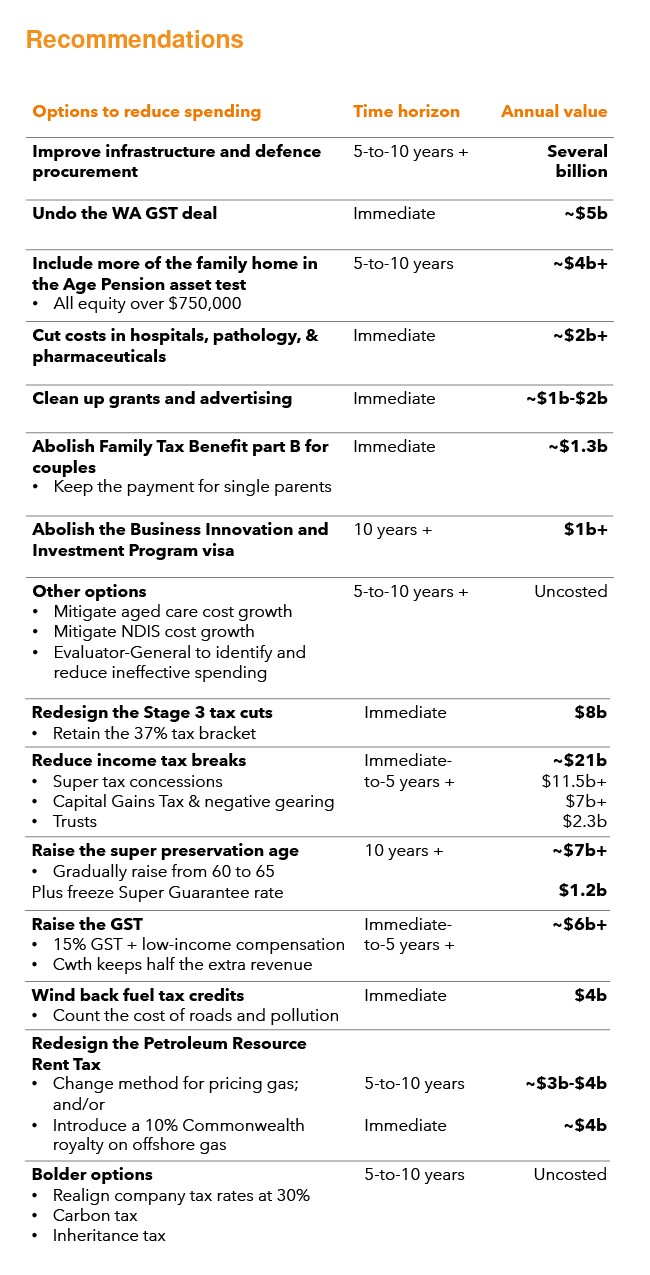

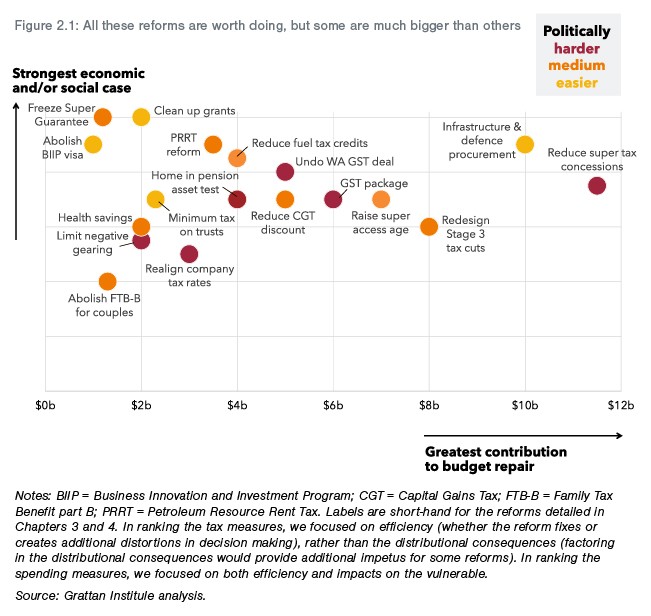

The Grattan Institute has released a new report on budget repair. Podcast version. It starts by noting that Australia’s structural budget deficit is expected to be about two per cent of GDP (almost $50 billion) a year, every year, by the end of this decade, and that the fiscal impacts of population ageing and of climate change imply additional budgetary strains lie ahead. Grattan argues that Australia is unlikely to be able to grow its way out of these problems and so the Institute proposes a range of spending cuts and revenue increases.

Source: Grattan Institute, Back in Black? A menu of measures to repair the budget.

Grattan also warns that governments will need to take measures to rein in cost growth in aged care and on the NDIS to preserve the sustainability of both programs. The report’s authors concede that no government would be able to pursue all its recommendations but claim that choosing several would be enough to put Australia ‘well on the way to tackling the structural budget deficit.’

Source: Grattan Institute, Back in Black? A menu of measures to repair the budget.

- Peter Martin on what’s driving soaring rents.

- Australia has agreed to temporarily suspend its appeal to the WTO over Chinese government tariffs on Australian barley pending an attempt to negotiate a settlement instead.

- A submission from the Productivity Commission on promoting economic dynamism, competition and business formation.

- ACCC Chair Gina Cass-Gottlieb gave a speech on the role of the ACCC and competition in a transitioning economy that restates the case for reform of Australia’s merger laws.

- Chapter 1 of the IMF’s April 2023 Global Financial Stability Report digs into the challenges posed by the interaction between tighter monetary and financial conditions and the build-up in financial vulnerabilities since the global financial crisis.) And here are short IMF blogs on the global economic outlook and the outlook for financial stability to accompany the new WEO and Global Financial Stability Report. The IMF’s April 2023 Fiscal Monitor has also been published.

- Meanwhile, the Economist magazine says the IMF faces a nightmarish identity crisis due to three problems: the intransigence of Chinese creditors when it comes to debt restructuring; middle income repeat offenders where the Fund is reluctant to lend due to inability to reform leading the IMF to be ‘too afraid to put serious money on the table, and too political to take it off altogether’; and mission creep with an increasing focus on World Bank-like issues.

- Also from the same magazine, why economics does not understand business.

- The WSJ’s Greg Ip considers the potential impact of ChatGPT on professional jobs.

- Kotlikoff and Miller argue that banking as we know it is dying, and that it’s time to end financial panics by arranging a transition to limited purpose banking.

- In the FT, Andy Haldane says the problem goes beyond banks – the state safety net is increasingly distended by support for households and businesses as well, creating a ‘doom loop’ of insuring risky behaviour.

- A Chatham House report reviewing how the international economic architecture has been responding to climate change.

- This American Enterprise Institute paper seeks to map and quantify the effect of malicious cyber activity on the US corporate sector.

- Tyler Cowen highlighted this AI Policy Guide from the Mercatus Center.

- The Odd Lots podcast in conversation with Nassim Taleb.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content