Australian households are scaling a $2.3 trillion mountain of debt, but how far can they climb?

The activities of consumers make up around 60 per cent of Australia’s GDP, the widely accepted measure of national output. That’s a bigger contribution to national “production” than those of the miners, banks, and various levels of government combined. The mood of households and how inclined they are to spend matters a lot for the overall performance of our economy.

For example, Australia’s rate of economic growth in the decade since the global financial crisis (GFC) has tracked below our usual trend rate of growth partly because so many households have been in an unusually cautious mood. Growth in consumer spending actually lagged behind real GDP growth for four straight years from 2012 — and the rest of the economy was unable to make up the difference.

In fact, only once in the past decade has our economy grown at trend. That was in 2012, when GDP growth was a healthy 3.9 per cent at the height of the mining investment boom. Household spending growth was also underwhelming that year, but soaring resources investment more than took up the slack.

The outlook for household spending will be the product of what are turning into variable crosswinds. So far, the healthy labour market is a tailwind, as have been previously rising house prices, which inflated household balance sheets. Moreover, another round of personal tax cuts are on the way and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) looks likely to maintain record low official interest rates for some time yet.

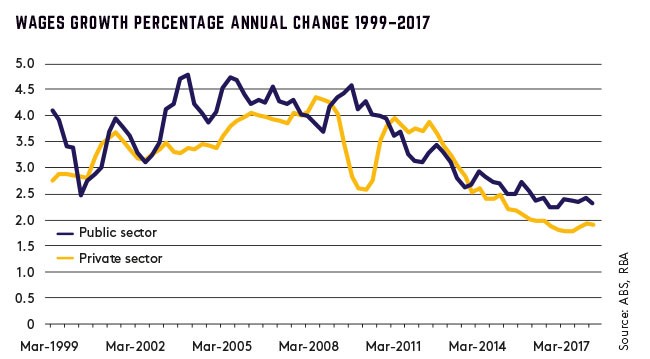

However, there are significant headwinds. Many households already are being buffeted by rising mortgage rates despite the RBA’s policy inactivity. Also, wages growth is the lowest in a generation, and consumer confidence is fragile. Finally, there are segments of the housing market showing some strain, particularly the more oversupplied inner-city apartment markets.

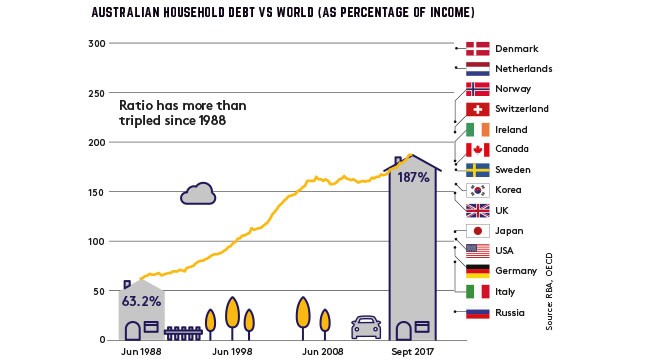

The biggest looming risk for consumers, though, is more long-term in nature. Since Australia’s last recession, more than a quarter of a century ago, the debt burden carried by households has exploded by more than threefold. We flagged the implications of this multi-year build-up of debt as the key vulnerability for our economy in the feature: “2018: The Five Key Economic Trends” published in the November 2017 issue of Company Director.

In absolute terms, the mountain of indebtedness now being scaled by consumers adds up to a record $2.3 trillion, double the level of a decade ago. The majority of this debt is in the form of home loans, which makes up three-quarters of the total. But, credit cards, personal loans and other forms of debt also are well represented. (Australians have more than 16.5 million credit cards accruing interest of more than $32.7 billion and an average debt of $4217, according to ASIC.)

We don’t have the highest household debt to income ratio in the world, but we’re close. A few countries in northern Europe boast higher household debt relative to income (see chart at left). Comparable ratios for the US, UK, Canada and New Zealand are sitting well below our own, even though these countries have had similar experiences to our own — outside the GFC, of course.

The unprecedented expansion in debt in the suburbs was partly fuelled by soaring house prices, which required buyers to increase borrowing simply to enter the major east coast markets. Meanwhile, generous lending standards were employed by the banks in happier times and the structural fall in interest rates since the 1990s greatly enhanced serviceability. One technicality here on measurement — the official debt to income ratio published by the RBA allows easy comparison across international borders, but can be misleading. It includes the income of all households, but the debt of only a subset of them.

Indeed, it’s important to take into account that only one-third of Australian households have a mortgage — another third rents, while the remaining third own their homes without a mortgage. So, the majority of the debt is skewed to a minority of households.

There is potential for the implications of the multi-decade build-up of debt in the household sector to be profound. What will happen, for example, when interest rates rise, which is all but certain over the next few years? What if wages growth stays close to record lows? Could house prices fall if the debt-servicing burden becomes too heavy? Is the stability of the major banks at risk? These questions are difficult to answer but, at least for now, the regulators do not sound alarmed. The RBA’s latest Financial Stability Review, for example, released in April, revealed that Australia’s financial system is resilient and performing well — although there are risks, as always.

It is possible to project what is likely to happen to the household debt-servicing burden as interest rates rise. First, let’s make a few assumptions. Let’s assume that over the next five years, household debt continues to rise at the current pace, alongside the existing rate of wages growth. Let’s also assume that the RBA raises the official cash rate two percentage points over the same period. Finally, let’s assume that the commercial banks pass on in full these RBA rate hikes to mortgage rates.

Under this scenario, the household debt-servicing ratio very quickly climbs from the current 12-year low. In fact, within the five years assumed, the servicing ratio soars to a new record high — and that is with a cash rate of just 3.5 per cent, still well below the long-term average rate of just over five per cent.

This simple experiment proves that only a small turn of the interest rate dial will deliver a bigger hit to household finances than did the record-high 17 per cent interest rates heading into the last recession. That’s what a tripling of the household debt to income ratio will do. Most households will adjust, but some won’t. Indeed, a growing number of respected economists believes that a possible crunch is coming for the more heavily indebted of households. There could be a severe impact on their finances and, potentially, on house prices — and even the banks.

House prices already are falling in the major cities, but this is more a symptom of pockets of oversupply and tighter lending standards. Demand from first-time buyers has also softened and there has been a crackdown on purchases by foreigners. However, there might be a more sinister explanation that becomes clear only with hindsight.

Still, the coming adjustment for households means many may have to eat into what now is discretionary spending. This means slower growth and even falls in spending on clothing, meals out, holidays and the like. The sluggishness of retail spending over the past couple of years hints that this process already may be underway.

A harder landing for households, like the subprime mortgage crisis in the US that helped trigger the GFC a decade ago, remains more of a risk than a reality. However, mortgage rates here are already rising and senior RBA officials have reminded us repeatedly that the next move in official interest rates will only be up.

For now, the potential adjustment for households remains a low rumble on the horizon. Whether these thunderclouds break depends on many things, including the pace with which the RBA normalises interest rates.

Moreover, the central bank will certainly slow the pace of rate hikes if the storm looks like becoming destructive.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content