Drought is a recurring feature of rural life in Australia, but its increased frequency may require a policy rethink.

Since systematic weather recording began in the late-19th century, Australia has experienced three prolonged, widespread droughts — the Federation Drought (1895–1903), the drought that coincided with WWII, and the Millennium Drought (2001–09). In between these episodes, there have been shorter, more localised, but often more severe droughts — in the mid-1960s, 1982–83, and the early 1990s. More recently, much of eastern Australia has been experiencing protracted dry conditions and, over the winter months, unusually high temperatures.

The most obvious economic impact of drought is on the volume of agricultural production, particularly of crops, which typically fall sharply during a drought, and then rebound strongly after the drought has broken. The impact on livestock products (meat and wool) is a little more complicated. Once drought conditions have become sufficiently established, livestock producers will seek to reduce their herds or flocks, resulting in a temporary increase in the recorded volume of meat production. When the drought breaks, recorded meat production typically falls as graziers focus on rebuilding their herds.

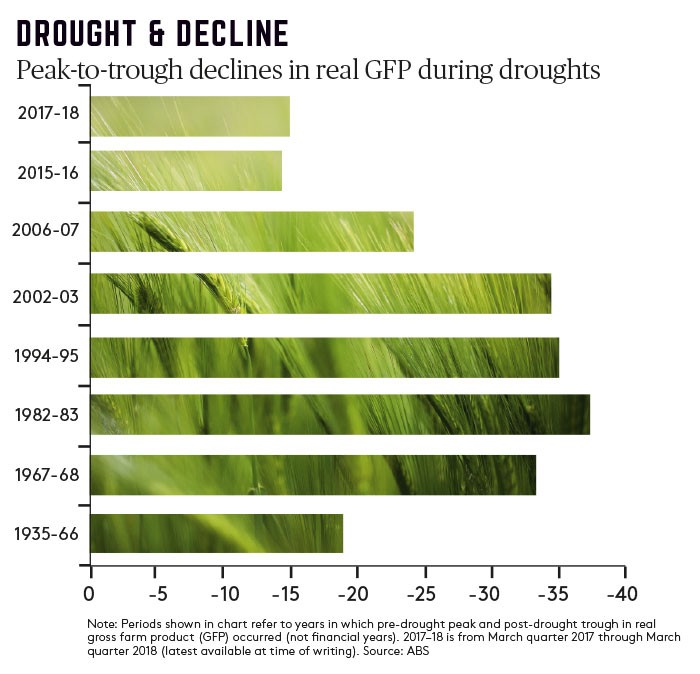

Declining real gross farm product

On average, over the past 50 years, Australia’s real gross farm product has declined by 27.5 per cent during droughts, measured from the peak quarter prior to the onset of drought to the lowest point during or after the drought (see chart).

The more recent droughts appear to have entailed a smaller decline in agricultural output than those of earlier decades. That’s because they have tended to be more regionally concentrated than those of the 1960s, ’80s and ’90s. Thus the current drought has been concentrated in Queensland and New South Wales, whereas Western Australia, which in recent years has accounted for a larger share of Australia’s crop production than any other state, has been experiencing more normal weather conditions.

Droughts can also affect the prices received for agricultural commodities. When a large decline in Australian production has a significant impact on global supplies — as is often the case with wheat — prices typically rise during drought, which can provide some partial offset for those growers who are able to produce a crop. However, the culling of herds and flocks during a drought typically results in an initial decline in livestock prices — which is then typically reversed during the herd rebuilding phase that follows.

Drought continues to have a serious impact on the fortunes of farming business and families, and the rural communities in which they operate. For example, sheep ear tags are compulsory in Victoria and one company was getting 30 enquiries a week. When the drought began to bite, enquiries shrunk to three a week. At AgQuip, Australia’s largest expo of farm machinery in Gunnedah, NSW, in August, attendance was high, but smart farmers were pushing hard for deals. Some farm machinery manufacturers, such as Kubota, could be bargained down to zero per cent interest on big tractor buys.

However, despite the recent reports of financial distress affecting farmers — with certain communities being disproportionately hit — drought impact on the broader Australian economy is now less significant than in earlier decades, largely because farming represents a smaller proportion of the economy than it once did. In the 1960s, farm product accounted for about 12.5 per cent (on average) of Australia’s GDP. The droughts of the mid-1960s directly subtracted an average of 2.5 percentage points from Australia’s real GDP growth (measured from peak to trough). By the early 1980s, farm product had declined to less than six per cent of GDP, so that the 1982–83 drought, although it resulted in a larger fall in agricultural production than any other in the past 50 years, “only” subtracted 1.5 percentage points from Australia’s overall growth rate. With farm production now accounting for about 2.5 per cent of Australia’s GDP, the more recent droughts have directly reduced Australia’s overall growth rate by less than one percentage point (although taking account of the harder-to-measure indirect effects would likely increase that figure).

Likewise, since agricultural commodities now account for just over 10 per cent of Australia’s total exports, compared with under 30 per cent in the early 1980s and more than 40 per cent in the 1960s, the impact of droughts on Australia’s external balance of payments is much less than in previous decades.

A second reason is that farmers are typically better prepared for drought than in earlier decades. That’s partly because of better weather forecasting, greater use of irrigation (in some instances) and more astute crop rotation or herd management. Farmers have also been able to make use of financial tools, such as farm management deposits, to “smooth” weather-induced fluctuations in their income.

As at the end of June, a record $6.6 billion was held in these deposits reflecting the record level of agricultural income (more than $60b) generated in 2017.

In addition, federal and state governments typically provide financial and other assistance to farmers and rural communities during periods of severe drought — as they are doing during this latest episode. The rising probability of an El Niño event this spring and summer implies that drought conditions in eastern Australia are likely to continue at least into the early part of 2019, which in turn means the economic impact of the current drought may eventually be similar to that of the early 2000s, subtracting around one percentage point from GDP over the course of two years. From a longer-term perspective, it seems droughts are occurring more often than in the 20th century.

That’s almost certainly a result of climate change — and mainstream science is telling us ongoing climate change will almost certainly bring higher temperatures, more frequent droughts, more frequent and damaging storms and floods, and higher rates of soil erosion. It could well be that farming, at least as conventionally practised, may no longer be sustainable in more drought-prevalent parts of the country.

If that’s a correct assumption, Australian drought-relief policies need to contemplate the possibility of some communities needing assistance to transition out of farming operations in the long term.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content