Business confidence dropped in June while consumer sentiment slumped in July. The Fed has signalled that it’s prepared to take out some insurance in the form of lower rates, prompting US share prices to jump. This week’s readings include new RBA working papers, defending Australia, business size and innovation in NSW, the changing nature of the China put and the outlook for global food prices.

Business confidence fell in June, reversing its previous jump in May. Business conditions did improve over the month but remain well below their long-term average. RBA rate cuts and government tax refunds were not enough to prevent consumer sentiment slumping to a two-year low in July.

Australia’s Council of Financial Regulators noted that, although housing loan arrears have been rising, to date risks to lenders from falls in house prices have been limited by low unemployment, low interest rates and improvements in living standards.

Lending to households for dwellings fell in May and in annual terms dropped by its most in about a decade.

Financial markets interpreted US Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s testimony to Congress as signalling that the Fed is set to cut rates at its 30-31 July FOMC meeting. US stock markets celebrated.

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

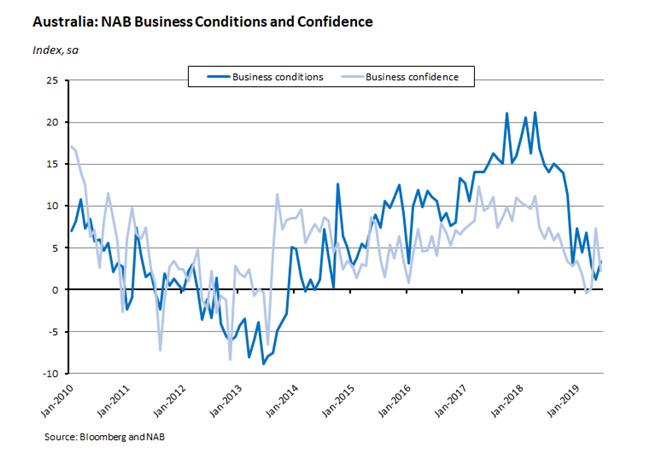

According to the NAB monthly business survey, Business confidence dropped by five points in June, with confidence declining across all industries other than retail (which saw a modest increase).

On a more positive note, business conditions rose two points in June, lifted by gains in the employment and trading sub-indices. June’s survey saw the employment index well above its long-run average but the trading and profitability indices below theirs. Overall, however, the business conditions index remains well below its long-run average level. By sector, conditions are strongest in mining, followed by the services sector and construction. The retail sector continues to be the weakest, followed by manufacturing, transport and utilities and wholesale.

Why it matters:

Back in May, the business confidence index had enjoyed a big, seven-point post-election increase. That was the largest monthly jump in the index recorded since 2013, although the accompanying analysis from NAB at the time cautioned that other forward-looking indicators suggested that the bounce was ‘likely to be short-lived’. That prediction looks to have been on the money: June’s decline in business confidence has unwound most of May’s increase, suggesting the lift from the election result and the RBA’s rate cut has already faded.

Conditions in the retail sector remain particularly weak, with levels of business conditions last seen in the depths of the GFC, as household spending remains constrained. On the other hand, business conditions improved markedly in the construction sector (up to an eight-month high), implying that here at least the RBA’s action to ease policy may have gained some early traction.

What happened:

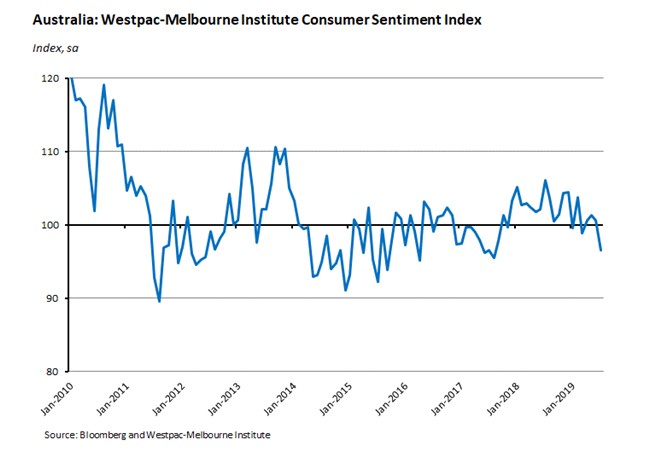

The Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index of Consumer Sentiment fell (pdf) 4.1 per cent in July to 96.5 from 100.7 in June, taking the index down to a two-year low and moving it back into the territory where pessimists outnumber optimists for the first time since March.

The main drivers of this month’s decline were sharp drops in views about economic conditions over the next 12 months and five years, and in expectations about family finances over the next 12 months. Views on family finances vs a year ago and time to buy a major household item were both up over the month (but down over the year). Confidence in the labour market also deteriorated in July, with an increase in the share of respondents expecting a rise in unemployment in the year ahead. The one bright spot was housing market sentiment, where the ‘time to buy a dwelling’ index delivered the first above trend reading in more than four years.

Why it matters:

In the commentary accompanying the release, Westpac noted that the fall in sentiment in July was ‘troubling’, coming as it did against the backdrop of a second 25bp rate cut from the RBA and the passage of the government’s tax package1. So although the announcement effect of easier monetary policy does seem to have been positive for the housing market, that hasn’t been the case for consumer sentiment more broadly, where rate cuts seem to have been treated more as a signal about the weakness of the economic outlook than as offering reassurance that a potential cure for that weakness was now being applied. June’s survey showed a similar response to the RBA’s first rate cut.

What happened:

Australia’s Council of Financial Regulators published its July 2019 quarterly statement. Among the factors included in the regulators’ discussions were:

- The housing market. The Council noted signs of stabilisation in the Sydney and Melbourne housing markets alongside continued soft conditions in other capital cities. Despite some sizeable price adjustments, they judged that risks to lenders from falls in house prices to date have been limited by the strength of the labour market, low interest rates and improvements in living standards. All that said, housing arrears have continued to edge higher.

- Credit growth. According to the Council, housing credit growth has stabilised at a relatively low level, with lending to investors remaining weak. Demand for housing credit has been subdued and supply has also seen some tightening. Business credit growth has weakened recently, with lending to small businesses declining over the past year.

- Policy changes. The Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) noted changes in its guidance on the minimum interest rate used in serviceability assessments for residential mortgage lending, announced on 5 July. The changes are in line with APRA’s earlier proposals outlined in the Weekly back in May and mean that banks no longer need to assess home loan applications using a minimum interest rate of at least seven per cent. Instead, they can set their own minimum interest rate floor and use an interest rate buffer of at least 2.5 per cent over the loan’s interest rate.

This week also saw APRA announce lower capital targets for Australian banks. Last November, the regulator had proposed that the four major banks be required to increase their total capital by four to five percentage points of risk weighted assets (RWA) over four years. Instead, it will now require them to lift total capital by three percentage points of RWA by 1 January 2024, based on concerns about a lack of market capacity to absorb the original proposed increase and the potential impact on bank funding costs. Meanwhile, the long-term aim of an additional four to five percentage point increase will remain while over the next four years APRA considers alternative approaches to raising the additional one to two percentage points. Separately, APRA has said that it will apply additional capital requirements to three of the major banks (ANZ, NAB and Westpac) to reflect higher operational risk identified in their risk governance self-assessments. This follows a decision in May last year to apply a capital add-on to CBA.

Why it matters:

The Council’s assessment of the housing market and credit conditions are in line with the data reported here over the past couple of months and contain no surprises. In terms of rising arrears, back in June the RBA’s Jonathan Kearns had noted that housing arrears as a share of bank housing loans had risen to around the level reached in 2010, the highest share for many years, albeit still well below the level reached in the early 1990s recession. However, he also pointed out that at around one per cent, the level of arrears was still relatively low both in absolute terms and compared to international experience.

APRA’s decision to change its loan affordability test is expected to boost the borrowing capacity of households and hence provide more support for the housing market. As such, it could work to offset some of the tightening in credit availability that has occurred over the past couple of years, albeit at the potential cost of adding yet more debt to households’ already heavily burdened balance sheets.

What happened:

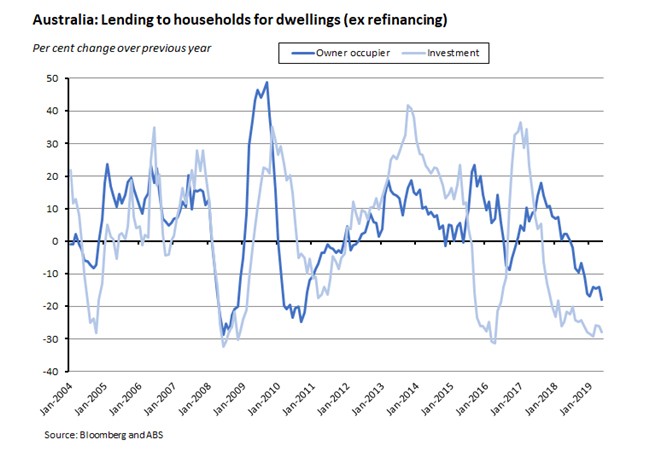

Lending to households fell 1.3 per cent (seasonally adjusted) over the month in May, following a 0.6 per cent rise in April.

Lending to households for dwellings excluding refinancing was down 2.4 per cent over the month and 20.9 per cent over the year, reflecting monthly drops in lending to households for owner occupier dwellings (down 2.7 per cent) and investment dwellings (down 1.7 per cent), leaving both series deep in negative territory in annual terms.

Lending to households for personal finance excluding refinancing was likewise down 0.7 per cent over the month and down more than 16 per cent from May 2018.

In contrast, lending to businesses jumped by 12.1 per cent in May over April and was up more than 34 per cent over the year.

Why it matters:

The near 21 per cent annual drop in housing finance commitments in May was the biggest fall in ten years. However, the May result predates the two rate cuts by the RBA and a post-election rebound in housing market sentiment which together have seen some signs of price stabilisation in the Sydney and Melbourne markets.

. . . and what I’ve been following in the global economy

What happened:

In testimony to Congress, Chair of the US Federal Reserve Jerome Powell fuelled market convictions that the Fed will cut rates later this month.

Powell said that the Fed’s ‘baseline outlook is for economic growth to remain solid, labour markets to remain strong and inflation to move back up over time to the Committee’s two per cent objective.’ But he then went on to flag an increase in uncertainties surrounding the outlook, noting that ‘economic momentum appears to have slowed in some major foreign countries’, that several ‘policy issues have yet to be resolved, including trade developments, the federal debt ceiling, and Brexit’ and that ‘there is a risk that weak inflation will be even more persistent than we currently anticipate.’ Referring to the June meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), Powell went on to note that ‘Many FOMC participants saw that the case for a somewhat more accommodative monetary policy had strengthened. Since then, based on incoming data and other developments, it appears that uncertainties around trade tensions and concerns about the strength of the global economy continue to weigh on the US economic outlook. Inflation pressures remain muted.’

The minutes of the June meeting have also been published, recording that ‘Participants generally agreed that downside risks to the outlook for economic activity had risen materially since their May meeting, particularly those associated with ongoing trade negotiations and slowing economic growth abroad.’ The minutes go on to report that ‘Although nearly all members agreed to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 2.25 to 2.5 per cent at this meeting, they generally agreed that risks and uncertainties surrounding the economic outlook had intensified and many judged that additional policy accommodation would be warranted if they continued to weigh on the economic outlook.’

The growing conviction that a Fed rate cut is on its way prompted a positive response by US stock markets, with the S&P 500 index (briefly) pushing through the 3,000 level for the first time.

Why it matters:

Investors and financial markets (and not forgetting some aggressive tweeting from President Trump) have been engaged in a kind of debate with the Fed over the need for rate cuts. On the case for patience, the Fed has been able to point to generally good economic outcomes including a record-long economic expansion, a strong Q1 GDP reading, and an unemployment rate that had fallen to a fifty-year low of 3.6 per cent in April and May of this year. Set against that have been fears about trade wars, signs of fragility in the global economy more generally, and subdued inflation.

Last week’s labour market report appeared to add more weight to the case for patience, with non-farm payrolls jumping by 224,000 in June, comfortably beating consensus forecasts of a 160,000 gain and representing a marked bounce from May’s weak 72,000 print. Granted, the unemployment rate did tick up a bit to 3.7 per cent in June, but that mainly seems to reflect more Americans joining the labour force. The strength of that result looks to have been enough to head off market expectations of a 50bp cut when the FOMC meets on 30-31 July, but left forecasts of a 25bp reduction intact.

The latest round of Fed communications seems to have locked in that expectation. One argument is that the Fed is taking out some insurance in case the more pessimistic outcomes start to materialise. According to the latest minutes, for example, ‘Several participants noted that a near-term cut in the target range for the federal funds rate could help cushion the effects of possible future adverse shocks to the economy and, hence, was appropriate policy from a risk-management perspective.’ Interestingly, the Fed Chair also appears to have discounted the latest trade truce between Washington and Beijing.

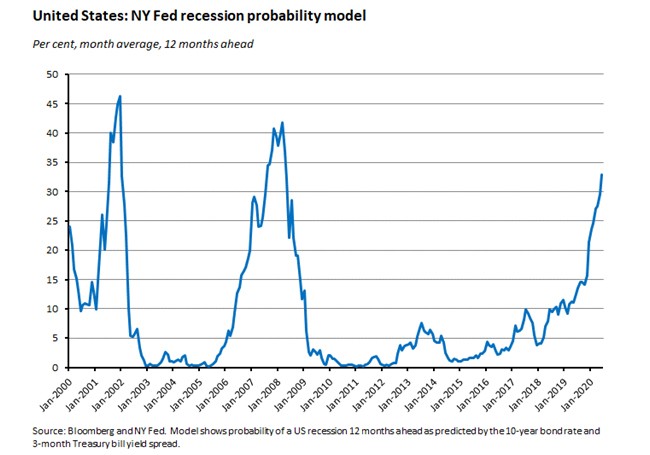

In this context, it’s also worth mentioning that the New York Fed’s measure of the probability of a recession in 12 months’ time rose above 32 per cent in June. That’s the highest level since 2009 and the measure has breached the 30 per cent threshold before every US recession since 1960.

Note that the model is based on the difference between the 10-year and 3-month Treasury rate, and as discussed in previous editions of the Weekly, there are reasons to be cautious about the current information content of this signal, despite its past successes as a recession indicator.

What I’ve been reading: articles and essays

An FT Editorial argues that recent decisions to loosen mortgage lending standards and scale back planned increases in bank capital requirements pose longer-term risks for the Australian economy, and that a better approach to slowing growth rests on tax cuts and increased public spending.

The RBA has released two new research discussion papers:

- A paper investigating the costs and benefits of ‘leaning against the wind’ (setting interest rates higher than purely macroeconomic conditions would warrant in order to address concerns about financial stability). The paper estimates that for Australia the costs of such a policy in terms of higher unemployment could be three to eight times larger than any benefit in terms of a lower probability of financial crisis, although the authors are also careful to note that there may be additional, hard-to-quantify benefits from such a policy, including the impact of low interest rates on households’ level of indebtedness and the associated negative economic effects.

- A paper looking at the effect of owner-occupier mortgage debt on consumer spending. Starting from the observation that the household debt-to-income ratio has risen to record levels in Australia while household spending has been relatively weak, the authors find evidence of a ‘debt overhang’ effect, whereby households cut back on their spending when they have higher levels of mortgage debt. They estimate that a 10 per cent increase in debt could reduce household expenditure by 0.3 per cent. Moreover, they find evidence of this overhang effect for both gross and net housing wealth – in other words, households reduce their spending even when the increase in the gross value of their debt is matched by an offsetting increase in the value of their assets (that is, net wealth remains unchanged). They also report that while indebted households reduce their spending by more than other households during adverse shocks, such as falling house prices, the negative effect of debt on spending also persists in more ‘normal’ times. The authors point out that since their results suggest that an increase in aggregate owner-occupier debt can constrain overall spending, they can also help explain the ‘puzzle’ of unusually weak household spending in Australia.

Treasury’s Meghan Quinn gave a speech on the role of economics in public policy.

Duncan Bentley on the Australian tax system in a digital age, and the need to protect taxpayer rights in the context of digital disruption.

Hugh White talks about how to defend Australia (this one is a podcast). White also sets outs his arguments here, and a there’s a critique here. Note that White reckons this kind of approach would require a defence budget of about 3.5 per cent of GDP (or four per cent with nuclear weapons) while critics suggest that his proposals would require a more radical restructuring of the Australian economy. Currently we are on track to raise the defence budget to two per cent of GDP by next financial year.

The NSW Innovation and Productivity Council (IPC) has released a report on business size, productivity and innovation. Large businesses (those with 200 or more full time equivalent employees or FTE employees) account for just 0.6 per cent of all employing businesses2 but earn 72 cents in every dollar of total employing business turnover, account for 58 per cent of exports and 52 per cent of jobs. At the other end of the size distribution micro businesses (1 – 4 FTE employees) account for 77 per cent of all employing businesses, just four per cent of turnover, six per cent of exports and 15 per cent of jobs. About 70 per cent of large businesses are involved in innovation activity compared to 36 per cent of micro businesses. About 57 per cent of other small businesses (5 – 19 FTE employees) and 61 per cent of medium-sized businesses (20 - 199 FTE employees) are involved in innovation activity.

Habib and Venditti review the global capital flows cycle and its drivers and argue that global risk is a key force, where financial shocks are slightly more important than US monetary policy in influencing that factor.

Barry Eichengreen thinks about what might bring the US record economic expansion to an end. An adverse geopolitical shock or a wage breakout and a Fed policy reaction are his two leading candidates.

The Bank of England’s Bank Underground blog investigates the long-run effects of uncertainty shocks, pointing to persistent negative effects on GDP, consumption, R&D investment and productivity growth.

Gavyn Davies warns that the UK economy is in danger of recession partly because Brexit-driven uncertainty has undermined investment spending, although he also notes that the UK labour market has remained buoyant.

James Kynge on the Communist party put. He argues that the kind of bounce markets saw in 2008 and 2014 is unlikely to be repeated, despite the hopes of some investors.

A new paper (pdf) from Acemoglu, Naidu, Restrepo and Robinson presents evidence that democracy has a positive effect on GDP per capita: their estimates imply that a country that transitions from nondemocracy to democracy achieves about 20 per cent higher GDP per capita in the next 25 years relative to a country that remains a non-democracy. Marginal Revolution’s Alex Tabarrok has some interesting thoughts on their results.

The Canadian model of pension provision faces challenges, which have in turn triggered a rise in leverage.

The Atlantic looks at a post-crisis Greece and the legacy effects across Europe.

The OECD-FAO agricultural outlook 2019-2028 reckons that real food prices will decline over the coming decade, helping consumers but putting farm incomes under pressure. Per capita food consumption of staple products (cereals, roots & tubers and pulses) has now levelled off globally, with future demand driven largely by population growth. Demand for higher value agricultural commodities (sugar, vegetable oils, meat, dairy) will grow faster, driven by a combination of rising per capita consumption and population growth. On the supply side, the Outlook expects continued productivity growth to see agricultural production increase by around 14 per cent over the coming decade while land use will be flat. Productivity growth will be powered by greater investment and technological catch up in emerging and developing economies and will allow growth in food production to outpace growth in demand.

1 While the bulk of the survey was completed prior to the tax package passing on 4 July, Westpac notes that this outcome had been widely predicted by media coverage earlier in the week.

2 In NSW there are also 904,000 non-employing businesses including sole proprietors, partnership and trusts. That compares to 271, 277 employing businesses.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content