The 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties or COP26 concluded in Glasgow on 13 November 2021 with nearly 200 countries signing on to the Glasgow Climate Pact.

Our primer on COP26 argued that Glasgow should be judged on how well it did in tackling three critical issues:

- First, in order to keep the world economy on track to meet the 2015 Paris Agreement (COP21) goals on limiting global temperature rises, the Glasgow Conference needed to deliver an agreement on how to get to carbon neutrality (net zero) by 2050. In particular, to ensure the credibility of that 2050 target it also had to deliver significant cuts in emissions by 2030. The original emissions reductions agreed in nationally determined contributions (NDCs) following Paris were inadequate to meet the goals set by COP21, and COP26 therefore had to produce significant upgrades to those NDCs.

- Second, COP26 also needed to secure a renewed and credible agreement from rich countries to meet their commitments under the Copenhagen Accord and Paris Agreement to collectively provide at least US$100 billion a year in financing for developing countries until 2025. It also needed to go further and meet the developing world’s expectations of additional financing beyond 2025. That financing would be available to help developing countries both with mitigation, by helping them reduce their own greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and with their adaptation to the effects of climate change that are already locked in.

- Third, Glasgow had to wrap up some important unfinished business from COP21 in the form of Article Six which focuses on voluntary cooperation in the form of market and non-market-based approaches to meeting climate goals, and in particular the Conference had to agree on the rules for international trade in emissions between countries and for a global carbon market for official carbon credits.

In addition to those three overarching goals, the UK hosts were also seeking to make significant progress on a range of related issues including phasing out coal, curbing methane emissions and halting deforestation.

Unfortunately, when judged against the three most important benchmarks, COP26 largely failed on two of them. It did not live up to the ambition of keeping the world on track to meet the temperature goals set by the Paris Agreement and it did not deliver either the promised outstanding amount of financing for developing countries or agree on a firm target for increased financing beyond 2025.

Despite those significant shortcomings, however, it’s also important to note that Glasgow did do enough to keep the show on the road. Based on the advanced text for the Glasgow Climate Pact (pdf), the negotiations did deliver progress – albeit limited and qualified progress – against most of the targets and ambitions listed above.

In more detail, and starting again with the big three:

- First, on mitigation, Glasgow did manage to move the world several steps forward on emissions reduction, including by securing net zero pledges from Russia (for 2060) and India (for 2070) for the first time and by persuading some countries to raise the level of ambition in their revised NDCs. Disappointingly, however, according to initial assessments of the revised NDCs, the collective total of country pledges will still not be sufficient to meet the Paris Agreement’s goals of limiting global warming to well below two degrees Celsius and preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels.Estimates by the UN Environmental Program suggest that even under an absolute best-case scenario in which all promises, pledges and national plans were implemented in full, warming would still be around 1.9 degrees Celsius (see the Annex for more analysis on this point).

- COP26 did attempt to correct for this failure to deliver sufficient emissions reductions– it managed to ‘keep 1.5 degree alive’ – by requesting that the Parties ‘revisit and strengthen’ the 2030 targets in their NDCs in order to align with the Paris Agreement goals, and do so by the end of next year and COP27 in Egypt. That represents an acceleration relative to the original Paris schedule, under which countries were only expected to revisit their NDCs every five years. The change to the timetable only applies for 2022, however, and some key emitters have already declared that they do not envision offering enhanced commitments on the grounds that their existing plans are sufficient.

- Second, on financing, the Glasgow Climate Pact ‘notes with deep regret that the goal of developed country Parties to mobilise jointly US$100 billion per year by 2020…has not yet been met.’ Instead, the Pact is limited to encouraging the world’s richest economies to fully deliver on the US$100 billion goal ‘urgently and through to 2025.’There was no firm commitment to make up for the shortfall in funding to date and no agreement on a funding target beyond 2025.

- Third, on finalising the Paris Agreement rule book, COP26 did succeed in delivering an agreement on rules, modalities and procedures for the mechanism established by Article Six paragraph four of the Paris Agreement (pdf), including by setting out standards for international emissions trading and by providing for the creation of a supervisory body that will oversee what will now become a new global carbon marketplace.

Glasgow also made progress on some of the other ambitions set out by the host.

- On coal, COP26 did fall short of the UK’s plan to ‘consign coal to history’ but for the first time a COP text did explicitly include mention of the fuel. The compromise text calls for ‘accelerating efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power.’ The wording here was watered down from ‘phase out’ to ‘phase down’ as a last-minute concession in response to pressure from India and China.

- In another first for the COP process, the Pact also included a call for the ‘phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.’While some see the inclusion of action on subsidies in a COP statement as a significant step, however, others have noted that the G20 for example has already regularly called for action in this area to little effect.

- On methane emissions, the Glasow Climate Pact ‘invites Parties to consider further actions to reduce by 2020 non-carbon dioxide GHG emissions, including methane’. In addition, more than 100 countries signed on to the Global Methane Pledge, agreeing to take national-level, voluntary actions to contribute to reducing global methane emissions by at last 30 per cent by 2030 from a 2020 baseline.

- On deforestation, Glasgow brought a Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use which saw signatories ‘commit to working collectively to halt forest loss and land degradation by 2030.’

- COP26 also produced a Declaration on Accelerating the Transition to 100% Zero Emission Cars and Vans which brought together a group of national, state, regional and city governments, car manufacturers, financial institutions and others to ‘work towards all sales of new cars and vans being zero emission…globally by 2040, and by no later than 2035 in leading markets.’

Finally, with the backdrop to COP26 having seen a ramping up of US-China geopolitical rivalry, and with much commentary around the absence from Glasgow of China’s Xi Jinping, it is also worth noting that the conference produced the US-China Joint Glasgow Declaration on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s.

This declared the intention of the two countries ‘to work individually, jointly, and with other countries during this decisive decade, in accordance with different national circumstances, to strengthen and accelerate climate action and cooperation aimed at closing the gap, including accelerating the green and low-carbon transition and climate technology innovation.’ The content of the joint declaration was less important than the symbolism of the two Superpowers agreeing to work together on climate policy.

The Annex below considers the big three items agreed at COP26 in more detail.

ANNEX: Additional detail on emission reductions, climate financing and carbon markets

Mitigation policies and aiming for net zero: the Paris Agreement goals are still out of reach

The most important objective for COP26 was to lock in upgraded NDCs that would deliver large enough emissions reductions to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. In particular, Glasgow was intended to get the world back on track to meet the more ambitious of the two temperature goals set by Paris – that of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius relative to pre-industrial levels. The text of the Glasgow Climate Pact duly resolves to pursue efforts to limit global warning to 1.5 degrees Celsius and states that it recognises that this requires ‘rapid, deep and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions, including reducing global carbon dioxide emissions by 45 per cent by 2030 relative to the 2010 level and to net zero around mid-century, as well as deep reductions in other greenhouse gases.’ The Pact also confirms that this ‘requires accelerated action in this critical decade.’ Importantly, then, Glasgow affirms not only the ambition of 1.5 degrees but also the measures needed to achieve it, including a 45 per cent reduction in emissions by 2030. At the same time, however, the text of the Pact also concedes that the actual pledges made to date will be insufficient to meet this goal, as it:

‘Notes with serious concern the findings of the synthesis report on nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement, according to which the aggregate greenhouse gas emission level, taking into account implementation of all submitted nationally determined contributions, is estimated to be 13.7 per cent above the 2010 level in 2030.’

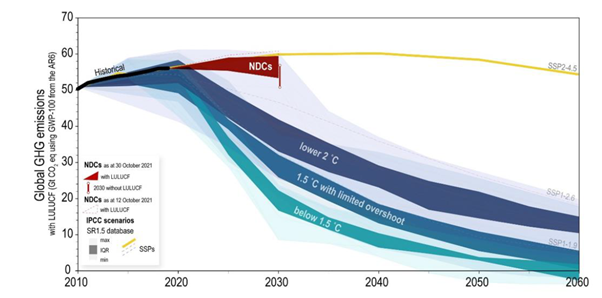

The references to a 45 per cent reduction in emissions by 2030 relative to 2010 and to net zero by 2050 are based on estimates from the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 degrees Celsius, which suggested that ‘available pathways that aim for no or limited (less than 0.1 degree) overshoot of 1.5 degrees would keep GHG emissions in 2030 to 25-30 gigatonnes (Gt) of carbon dioxide equivalent, or about 45 per cent of 2010 levels, and reach net zero by around 2050.’ Those same estimates also suggested that limiting warming to two degrees would require a 25 per cent reduction in emissions on 2010 levels by 2030 and reaching net zero by around 2070.

But as the Pact itself admits, the United Nations’ Nationally determined contribution synthesis report (pdf) released on 4 November has estimated that total global GHG emissions in 2030 would be about 53.8 Gt, which would imply that global emissions would on average be 13.7 per cent higher than in 2010. That is, a long way off even from the 25 per cent reduction required to limit the world to two per cent warming, let along the 45 per cent reduction targeted in the Pact.

Source: UN Nationally determined contribution synthesis report. The chart compares the total GHG emission level resulting from the latest available set of NDCs with the emission levels for three scenario groups: one in which the global mean temperature rise is kept below 1.5 degrees at all times; one in which warming is kept at around 1.5 degrees with a potential limited overshoot followed by a decrease to below 1.5 degrees by the end of the century; and one group that implies warming of above 1.5 degrees but below two degrees.

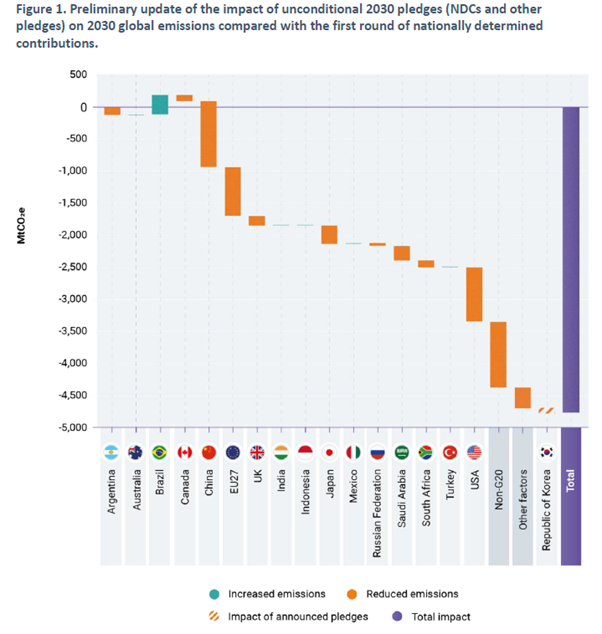

Those numbers line up with the UN Environment Programme (UNEP)’s latest update to its Emissions Gap Report 2021 (pdf). This provides a preliminary assessment of the implications of the new or updated NDCs delivered as part of the COP26 process along with other 2030 mitigation pledges and net zero announcements made since the initial Emissions Gap Report 2021 (that was cited in our earlier COP26 Primer).

The UNEP estimates that the aggregate impact of all new or updated unconditional NDCs and other announced pledges would only lead to a total reduction in 2030 global GHG emissions of about 4.8 Gt compared with previous pledges (that is an additional 0.7 Gt of emissions reductions relative to the UNEP’s previous assessment released earlier this year). The key drivers of the latest projected fall in emissions reflect reductions from Saudi Arabia, China and non-G20 members along with other factors including lower projections of international aviation and shipping emissions.

Source: Addendum to UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2021

According to the UNEP, projected emissions in 2030 under the unconditional NDC and pledges scenario are now on target to hit 51.5 Gt while if conditional NDCs are also included (these are NDCs that are contingent on a range of possible conditions such as the ability of national legislatures to enact the necessary laws, action from other countries, and the realisation of financial and technical support, for example) then projected emissions would fall to 48 Gt. Again, these estimates are significantly higher than the 25-30 Gt estimated by the IPCC as needed to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, with the UNEP report concluding that even after considering the latest round of commitments, annual global GHG emissions would still need to be ‘roughly halved’ to be consistent with a 1.5 degrees least-cost pathway.

In terms of the implications for global warming, the UNEP estimates that a continuation of current policies would limit warming to 2.8 degrees with a 66 per cent probability over the current century. When the effects of the full implementation of all unconditional and conditional NDCs are projected out to 2100, warming is then projected to be limited to 2.7 degrees and 2.5 degrees respectively. Go further and include the full implementation of all net zero pledges and announcements to date plus unconditional and conditional NDCs, and then warming over the 21st century is projected to be limited to 2.1 degrees and 1.9 degrees, respectively. However, the UNEP also warns that:

‘…given the lack of transparency of net-zero pledges, the absence of a reporting and verification system and the fact that few 2030 pledges put countries on a clear path to net zero emissions, it remains uncertain if net zero pledges will be achievable.’

The NDCs and other pledges that underpin COP26, then, still leave the world some distance from meeting the ambitions set by Paris and COP 21.

The Glasgow Climate Pact seeks to address this shortcoming by requesting Parties ‘to revisit and strengthen the 2030 targets in their nationally determined contributions as necessary to align with the Paris Agreement temperature goal by the end of 2022, taking into account differential national circumstances.’ Note, however, that this is only framed as a request as the Pact itself is non-binding and has no enforcement mechanism, and several important countries have already indicated that they are unlikely to offer up new pledges.

Climate Finance Commitments for developing countries: Behind schedule and under budget

After setting ambitious new NDCs, the second big task for COP26 was for rich countries to stump up more funding for developing countries. At COP15 the Copenhagen Accord of December 2009 saw developed countries promise that they would provide funding for developing countries to reduce GHG emissions (mitigation) and to adapt to the inevitable effects of climate change (adaptation), by providing US$30 billion for the period 2010-2012 and by pledging to mobilise long-term finance of a further US$100 billion a year by 2020. Later, the 2015 Paris Agreement reaffirmed the obligation of developed countries to provide financial support for both mitigation and adaptation, reiterated the goal of US$100 billion per year by 2020, and extended the promise of annual funding at this rate out to 2025.

Rich countries, however, have failed to live up to their promises. On the eve of the Glasgow conference, the latest OECD assessment reported that total climate finance provided and mobilised by developed countries for developing countries stood at just US$79.6 billion in 2019, and added that although ‘appropriately verified data for 2020 will not be available until early next year it is clear that climate finance will remain well short of its target.’ Part of the challenge is that there is no formal schedule for allocating monetary contributions by state, although recent work (pdf) by the UK’s Overseas Development Institute (ODI) claims that of the 23 developed countries responsible for providing international climate finance, only Germany, Norway and Sweden have been paying their ‘fair share’ towards the US$100 billion target.

As noted above, the Glasgow Pact ‘notes with deep regret that the global of developed country Parties to mobilize jointly US$100 billion per year…has not yet been met.’ It ‘calls upon developed country Parties to provide greater clarity on their pledges’ and also ‘urges developed country Parties to fully deliver on the US$100 billion goal urgently and through to 2025.’ But that still leaves the shortfall in place for now and offers no agreement on the scale of funding post-2025.

Developing countries had also been hoping for COP26 to make some progress on funding towards loss and damage (sometimes described as ‘climate reparations’) associated with the impact of climate change. But while Glasgow did acknowledge that ‘climate change has already caused and will increasingly cause loss and damage,’ developing countries did not manage to secure a hoped-for ‘Glasgow loss and damage facility’ to provide significant financial support. Instead, they got a commitment to ‘establish the Glasgow Dialogue between Parties, relevant organisations and stakeholders to discuss the arrangements for the funding of activities to avert, minimize and address loss and damage associated with the adverse impacts of climate change.’ The Glasgow Pact also decided that the Santiago Network would be provided with funds to support technical assistance ‘for the implementation of relevant approaches to avert, minimise and address loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change in developing countries.’ But the relatively small sums associated with technical assistance are a long way from the scale of financial commitment developing countries had wanted.

One area where poorer countries did enjoy some progress on the financial front was in the area of climate funding for adaptation purposes. Although Copenhagen and Paris had proposed funding should support both mitigation and adaptation, there has also been a broad recognition that to date funding has been skewed heavily towards the former, at least in part because mitigation projects (such as renewable energy projects) are seen as offering better investment prospects. The Glasgow Pact says that developed countries should ‘at least double their collective provision of climate finance for adaptation to developing country Parties from 2019 levels by 2025, in the context of achieving a balance between mitigation and adaptation in the provision of scaled-up financial resources.’

Emissions trading and a global carbon market: Putting a rulebook in place

The third critical objective for COP26 was to complete the ‘rulebook’ for the Paris Agreement as it applied to Article Six in general and to paragraphs two, four and eight in particular. The first two of these refer to market-based approaches to trading emissions, with one focused on allowing countries to trade credits on a bilateral basis to meet their Paris commitments and the other establishing a market for multilateral exchanges, while the third relates to aid and other non-market mechanisms:

- Article Six, paragraph two (A6.2) focuses on allowing Parties to trade mitigation outcomes (such as emissions reductions) so that those countries that have over-performed on meeting their Paris Agreement commitments can then sell the ‘excess’ to countries that have under-achieved. Operationalising A6.2 involves regulating bilateral trade in these so-called ‘Internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs) in a way that will permit countries to meet their NDCs via ITMOs without undermining the credibility of the emissions reduction process. ITMOs could also provide a mechanism for the international recognition of cross-border trade linking subnational, national, regional and international carbon pricing initiatives. COP26 now provides the formal guidance on the treatment of ITMOs.

- Article Six, paragraph four (A6.4) establishes a ‘mechanism’ for countries to contribute to GHG emissions reduction, effectively through the creation of a new global carbon market. COP26 adopts the ‘rules, modalities and procedures’ for this market and also designates a Supervisory Body that will oversee it. While A6.2 is focused on country-to-country trade in carbon credits, A6.4 is about setting up a framework for trading in official carbon offsets by both the public and private sectors.

- Article Six, paragraph eight (A6.8) focuses on non-market approaches to sustainable development and climate change.

A6.4 and the establishment of a global carbon market in particular has come to be seen as an essential step in producing some agreed rules, standards and credibility to international carbon markets. As the focus on climate change has increased, and with a growing number of companies adopting their own net zero targets, the global economy has seen a dramatic boom in the demand for carbon offsets. Critics, however, have charged that the lack of any credible oversight creates significant risks around this process, including the danger of a proliferation of low quality offsets, the possibility of widespread double-counting (or even multiple-counting) of emissions reductions, the spread of inconsistent standards, and issues around the verification of claimed emissions reductions.

The idea of the Paris Agreement and A6.4, then, was to create a formal mechanism that would provide an official market for offsets that apply to NDCs along with a consistent set of standards. COP26 has delivered the underpinnings of that mechanism, setting up an UN-certified instrument that can be internationally traded. An A6.4 emission reduction or carbon credit (an A6.4ER) will now be set equal to one tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent, and be calculated in accordance with the methodologies and metrics adopted by the Parties to the Paris Agreement. (Note, however, that the detail of the new rules only applies to official A6.4ERs and not to the voluntary market which currently services a large amount of private sector demand for offsets.)

Turning to those rules, the Glasgow Climate Pact sets out: agreed rules around participation in the carbon market; guidance on the nature of the activities that would be eligible for inclusion in that market; requirements around the methodologies to be used for setting the baseline for emissions reductions, for demonstrating the additionality of emissions reduction activity, for accurately monitoring emissions reductions and for calculating the reductions achieved by the activity; and rules around the process for validating claimed reduction activities.

It also establishes a new Supervisory Body to oversee this new carbon market. The latter will comprise 12 members from Parties to the Paris Agreement, with two members from each of the five UN regional groups, one member from the least developed countries and one member from small island developing states, with members (and their alternates) each elected for a term of two years, except for the first election when the term will be three years.

The negotiations around Article 6 have been contentious with several areas of dispute.

The first of these related to the treatment of old carbon credits and in particular the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). Critics had argued that allowing a full recognition of all Kyoto Protocol credits would undermine the objective of achieving lower emissions, since it would involve including a large number of credits that would provide little or no additional emissions reductions, as they relate to emissions that have already been achieved. The compromise deal reached at COP26 was that the use of old CDM credits will now be restricted to those generated after 2013 up to 2020. After 2020, the agreement also allows for CDM projects to request to transition to the new A6.4 mechanism.

The second dispute related to concerns over double-counting. The issue here was that if (say) one country implemented a project to reduce emissions – for example, a renewable energy project – and then sells sold credits for those emissions reductions to a second country, there would be risk that both countries would then seek to claim the emissions reductions that had been generated by the project as part of their NDCs. In this case, the Glasgow Pact requires ‘corresponding adjustments’ to be made for all A6.4ERs and for all ITMOs under A6.2 in order to rule out the use of the same emission reductions by more than one Party. That is, the rules state that country A can’t claim this emissions reduction as part of its own NDC if it has also been bought by country B to meet its NDC but rather country A must make a ‘corresponding adjustment’ and add the emission reductions from the project back into the total emissions count.

The Glasgow deal also requires a minimum of two per cent of newly issued carbon credits under the arrangement to be cancelled – to deliver emissions cuts – and a five per cent share to be transferred to an account used to assist vulnerable developing counties to meet the costs of adaptation to climate change.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content