What does the 2019 Federal Budget mean for your organisation and for the wider Australian economy? AICD Chief Economist Mark Thirlwell and Head of Policy Christian Gergis provide their analysis of major budget initiatives.

Main points

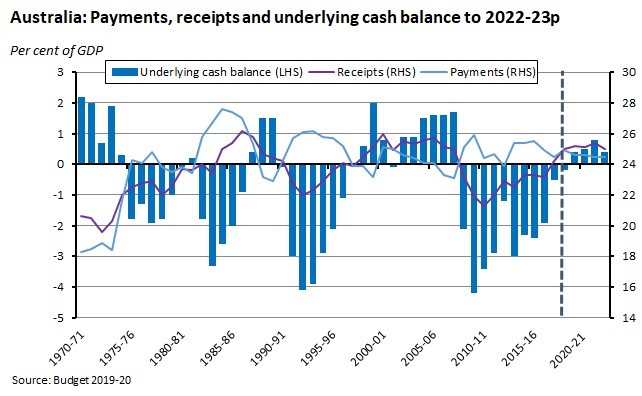

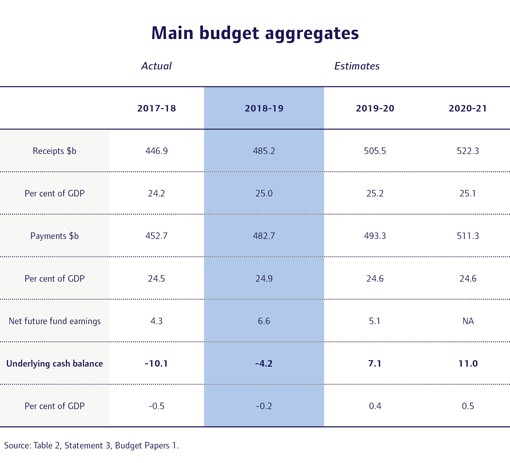

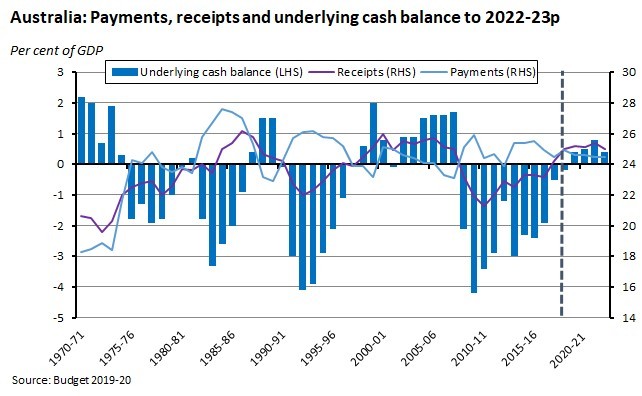

- Back to surplus. The budget targets an underlying cash surplus of $7.1 billion (0.4 per cent of GDP) in 2019-20, following on from an estimated deficit of just $4.2 billion (0.2 per cent of GDP) in 2018-19. Surpluses are then forecast to build across the forward estimates period.

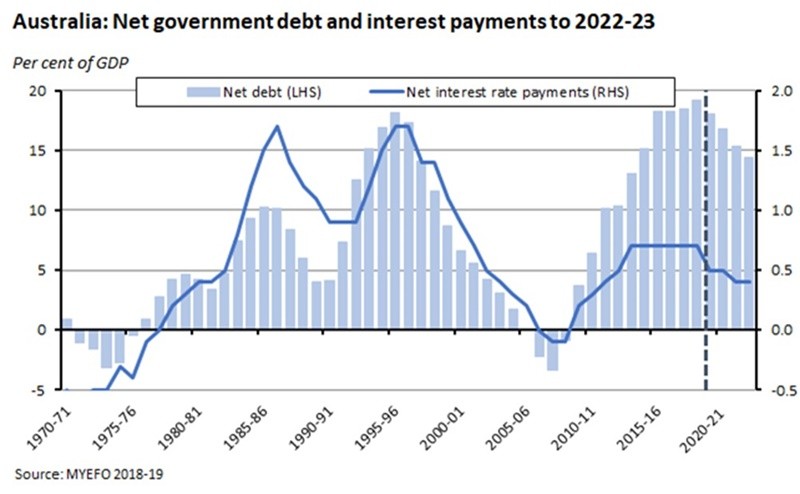

- Gross debt as a share of GDP is forecast to decline in each year of the budget estimates, falling from 27.9 per cent of GDP in 2019-20 to 12.8 per cent of GDP by 2029-30. Net debt is expected to decline from 18 per cent of GDP in 2019-20 to zero per cent by 2029-30. The government’s net financial worth is expected to improve in parallel.

- Real GDP is forecast to grow at around its estimated potential rate of 2.75 per cent in 2019-20 and 2020-21. Unemployment is forecast to stay at five per cent and Treasury still expects to see a pickup in wage growth.

- The budget offers short-term tax relief to low- and middle-income Australians and provides additional support for small businesses.

- For small businesses the budget increases the instant asset write-off threshold and also expands access to medium-sized businesses with an annual turnover of less than $50 million. The government also plans to bring forward the reduction in the company tax rate for small businesses.

- The government has increased its planned spending on infrastructure, and now intends to deliver a total of $100 billion of investment over the next decade (including existing commitments), with a focus on ‘busting congestion’ and improving connectivity.

- The budget messages focus on the symbolism of a return to surplus after more than a decade as a powerful emblem of good economic management; the delivery of income support to stretched households to help ‘ease the cost of living’; a promised future reduction in the overall income tax profile; support for small business; and a continuing commitment to infrastructure investment.

- The Budget saw few new governance policy measures, with the most significant package being a total of $606.7m over five years to facilitate the Government’s response to the Financial Services Royal Commission. Much of this funding had already been previously announced however, including, most significantly, much greater resourcing for the financial regulators, ASIC and APRA, for tougher enforcement.

- The key short-term risk to implementation of budget outcomes is of course the looming election. In terms of economic risks, it’s worth remembering that while commodity prices and the terms of trade can giveth, they can also taketh away. Higher commodity prices have provided a useful boost to budget revenues, but the longevity of these gains is – as always – questionable. The assumption of an economy growing at around trend is also subject to downside risks given the soft start to this year and the still-challenging global environment.

Overview

A budget will always be a product of its times, and this one is no exception. Four key factors have influenced the latest fiscal offering.

First and most obviously, an election is imminent, and the polls have been looking unhelpful for the incumbents.

The political message from Budget 2019 therefore seeks to combine long-running messages about the payoff from fiscal responsibility in the form of an end to (more than) ‘a decade of deficits’ and a return to surplus with a vote-attracting offer to the households that have not only contributed to at least some of that budgetary heavy lifting thanks to a steady rise in the tax-to-income ratio, but which are currently being squeezed by an uncomfortable combination of falling house prices and sluggish income growth. This is couched in terms of providing support to ‘ease the cost of living’ but in other circumstances could equally have been sold as a form of fiscal stimulus.

Second, as we flagged in our recent budget preview, the government’s coffers have once again benefitted from a series of strong outcomes for commodity prices – for iron ore and metallurgical coal in particular – and also from strong employment growth. Low inflation has helped too. Taken together, this has delivered some useful fiscal room for manoeuvre. Just as the previous budget benefitted from the nice surprise of tax revenues running comfortably ahead of Treasury projections, so has the current budget enjoyed a similar windfall.

Third, and in stark contrast to the positive nominal story about the economy, the real economy looks relatively weak, despite the budget papers’ description of an economy ‘in fundamentally good shape’. Real GDP growth for 2018 as a whole may have come in at a fairly respectable 2.8 per cent, but last year was very much a story of two halves. And while the first half saw annualised growth roaring along at close to four per cent, the second saw that plummet to less than one per cent. Moreover, in per capita terms, GDP growth contracted for the final two quarters of 2018 (hence headlines earlier this year proclaiming a ‘per capita recession’). There are signs that prominent elements of that economic weakness (slow household income growth in particular) have continued into this year, and that in turn has seen financial markets expecting the RBA to ease monetary policy at some stage (although not today!). But with the policy rate already at record lows and the supply of conventional monetary policy ammunition running low, those circumstances make a reasonably compelling economic case for fiscal stimulus (or alternatively, ‘support for households to manage the cost of living’).

Fourth, last year’s budget saw the government deliver a significant increase in infrastructure spend. The budget signals that there is more to come on that front, which has the twin advantages of delivering continued support to near-term growth and (assuming that the right projects are delivered) supporting the medium-term productivity outlook for the economy.

Finally, returning to that first point, it’s worth remembering that this budget effectively represents the start of an election campaign. The pitch has been influenced by that timing and its fate will be determined by how that campaign unfolds.

Economic assumptions – growth at potential and gradual increase in wages

Real GDP is forecast to grow by 2.75 per cent in 2019-20 and 2020-21 (that is, at around Treasury’s estimate of the economy’s potential growth rate), with activity supported by positive contributions from consumer spending, business investment and export growth. Household consumption growth is forecast to run at 2.75 per cent in 2019-20 and three per cent in 2020-21, helped by wage growth of 2.75 per cent and 3.25 per cent, respectively. While growth in employment is forecast to slow, the unemployment rate is expected to remain unchanged at five per cent. The Treasury hopes that the income tax relief, plus continued low interest rates, will help provide some needed support for growth in disposable incomes.

After growing by an estimated five per cent in 2018-19, nominal GDP is forecast to grow by 3.25 per cent in 2019-20 and 3.75 per cent in 2020-21, reflecting a decline in commodity prices from their current elevated levels.

Given the soft start to the current year, the ongoing adjustment in housing markets, and the still sluggish pace of wage growth, risks to these forecasts for the Australian economy are skewed to the downside, with the budget papers highlighting the risks posed by a more subdued outlook for household income and high levels of household debt.

Banking on commodity prices, again

As always, budget outcomes remain sensitive to assumptions about commodity prices. We know that revenues have been boosted by higher commodity prices and higher export earnings. According to the latest (March 2019) Resources and Energy Quarterly (REQ), Australia’s resource and energy export earnings are expected to reach a record high $278 billion in 2018–19 (including record earnings for thermal and metallurgical coal) before falling back over the following five years. Supply problems, mostly in other producing economies, have seen prices rise to seven-year highs, and revenues have then been further boosted by weakness in the Australian dollar against the greenback. As a result, the new REQ increased its estimate for export earnings this year by $13.8 billion relative to the projections in December’s REQ. Forecasts for resource and energy export earnings in 2019-20 have been upgraded by even more – $31 billion relative to December’s forecasts – with projected earnings of $272 billion for the year.

The budget reflects these developments. The iron ore price is forecast to fall over the course of the year to reach US$55/tonne by the end of the March 2020 quarter while the metallurgical coal price is forecast to fall to US$150/tonne by the same time. These forecasts matter. Sensitivity analysis notes, for example, that if the iron ore price were to fall to US$50/tonne four quarters earlier than assumed, nominal GDP could be $10.6 billion lower in 2019-20 than forecast, leading to tax receipts being $2.6 billion lower than expected. Similarly, if the trajectory for the expected fall in metallurgical coal prices were to be brought forward by four quarters, that would see nominal GDP lower by about $5.7 billion in 2019-20 and tax receipts would be about $0.9 billion lower in the same year.

Supporting households

As was pointed out in a recent RBA speech by Luci Ellis, Australian households have been doing some of the heavy lifting in terms of budget repair. Part of that reflects the familiar mechanism of bracket creep: even with low wage growth, taxpayers will still find themselves gradually being shunted into higher tax brackets. The rule of thumb is that, assuming no inflation adjustments to tax brackets, for every percentage point of growth in household income, taxes paid by households will on average increase by about 1.4 percentage points. But as Elis points out, over the past year, taxes paid by households increased by around eight per cent, or more than double the rate of growth in gross household income of 3.5 per cent, implying a ratio over two-to-one. Moreover, as this effect has been sustained for more than half a decade now, the share of income paid in tax has been rising steadily, over a period when income growth itself has been quite lacklustre. Explanations include a decline in tax deductions and offsets along with boosts to revenues from increased compliance and the use of technology.

That combination of sluggish income growth and rising tax takes is unattractive economically – private consumption is a key driver of the economy – and politically. It’s no surprise then, that the budget has targeted households for some relief in terms of measures to ‘ease the cost of living’. The economics and the politics are mutually reinforcing here.

The headline budget numbers – Back into surplus (well, next year)

The big – but far from unexpected – budget news is that the government expects to deliver the first surplus in more than a decade. But it will have to wait for the next financial year to do so.

Main budget aggregates

After a small deficit of just 0.2 per cent of GDP estimated for 2018-19, the underlying cash balance is projected to move into a modest surplus equivalent to 0.4 per cent of GDP in 2019-20, followed by a slightly larger surplus (0.5 per cent of GDP) in the following year.

Government receipts are expected to rise from 25 per cent of GDP in 2018-19 to 25.2 per cent of GDP in 2019-20, while payments are forecast to fall from 24.9 per cent of GDP to 24.6 per cent of GDP over the same period.

The shift to surplus – and projected ongoing surpluses over the budget projections – is good news for the debt profile. Gross debt as a share of GDP peaked in 2017-18 at less than 30 per cent of GDP and is forecast to fall to 12.8 per cent of GDP over the medium term. Net debt as a share of GDP is now expected to peak in 2018-19 at 19.2 per cent of GDP before falling slightly to 18 per cent in 2019-20. By the end of the forward estimates, the net debt burden is projected to have fallen to 14.4 per cent of GDP and by the end of the medium-term projections (in 2029-30) the net debt is projected to have been eliminated altogether.

Main corporate governance issues

The Budget saw few new governance policy measures, with the most significant package being a total of $606.7m over five years to facilitate the Government’s response to the Financial Services Royal Commission. Much of this funding had already been previously announced however, including, most significantly, much greater resourcing for the financial regulators, ASIC and APRA. Specifically, the two regulators will receive:

- $404.8 million over four years from 2019-20 for the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) to implement its new enforcement strategy and expand its capabilities and roles in accordance with the recommendations of the Royal Commission; and

- $145.0 million over four years from 2019-20 to strengthen the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) supervisory and enforcement activities which will support its response to key areas of concern raised by the Royal Commission, including with respect to governance, culture and remuneration.

The budget announcements provide a greater breakdown of how the additional ASIC and APRA funding outlined above will be ear-marked, including:

There is also $35.5m provided to create a new criminal jurisdiction of the Federal Court, which is aimed at ensuring those who have engaged in financial sector misconduct are promptly prosecuted (again, an announcement made in the lead-up to the budget).

Other policy measures for directors to note include expanding and extending the ATO’s Tax Avoidance Taskforce on Large Corporates, Multinationals and High Wealth Individuals, with $1bn to be allocated over four years from 2019-20. This measure is estimated to have a gain to the budget of $3.6bn over the forward estimates, with the additional funding to allow the ATO, amongst other things, to increase its scrutiny of specialist tax advisers and intermediaries that promote tax avoidance schemes and strategies.

In an effort to lift standards in the public sector, $104.5m will be provided to establish a Commonwealth Integrity Commission for the four years from 2019-20. The creation of the Commission – already announced in December 2018 – will operate as an independent statutory agency tasked with the investigation of corruption by Commonwealth employees.

Main risks – Election, growth and the commodity cycle . . . and the long-term outlook

Inevitably, the main risk to the budget in terms of implementation is the imminent election, which according to press reports is likely to be called within days. Excluding any measures that the government may be able to push through parliament in that very small window, the budget will remain hostage to the election results. And of course, the further out the proposed changes are, the greater the uncertainty around their future implementation.

And as always, budget outcomes remain vulnerable to economic ones. The global economy has had a tough start to the year, and the levels of policy uncertainty remain troublingly high. The budget judges that growth in Australia’s major trading partners remains solid and that helps underpin the economic projections, but there are clearly substantial risks around the international environment.

That also holds true in terms of the domestic economic environment. As the budget papers note, Australia is on track to record its 28th consecutive year of economic growth, has seen more than 1.2 million jobs created since September 2013, and just enjoyed a recent decline in the unemployment rate to 4.9 per cent. That’s a pretty decent backdrop. Unfortunately, however, that’s only part of the story. As we’ve already noted, current economic conditions look fragile in several respects, and the risky nexus of the housing market correction, household balance sheets and weak household income growth represent a big downside risk. The support to incomes provided by the budget is welcome in this context, but whether it will be enough to restore household confidence remains to be seen.

All Australian budgets face a familiar risk in terms of their significant reliance on commodity earnings and this time will be no exception. We have been enjoying a short run of upside surprises in terms of commodity prices, and current projections suggest that the near-term outlook remains positive. But any big shift in the global economy would call those projections into question, and some of the drivers are clearly temporary in nature. And, of course, sitting behind this is the recurring challenge for Australian chancellors of implicitly basing revenue and spending commitments around large and potentially reversible commodity price swings.

Finally, the budget position will continue to face long-term challenges reflecting factors such as the relatively disappointing pace of productivity growth and shifting demographic trends. Just this week, for example, the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) warned that Australia’s ageing population could simultaneously subtract 0.4 percentage points from the annual real growth in revenue while add 0.3 percentage points to the annual real growth in spending over the next decade. In real terms, that would equate to an annual cost to the budget of around $36 billion by 2028–29 (larger than the projected cost of Medicare in the same year).

Selected revenue measures

Key revenue measures announced in the budget included:

A series of measures aimed at lowering personal income tax burdens and providing support to households:

- Lower taxes for individuals through the non-refundable lower and middle income tax offset (LMITO), with a reduction in tax provided by the LMITO increasing from a maximum amount of $530 to $1,080 per annum for singles or up to $2,160 for dual income families for the 2018-19 through to2021-22. The base amount will also increase from $200 to $255.

- From July 2022, an increase in the top threshold of the 19 per cent personal income tax bracket from $41,000, as legislated under the existing Personal Income Tax Plan, to $45,000.

- From July 2022, an increase in the low income tax offset (LITO) from $645, as legislated under the existing plan, to $700, along with a more graduated withdrawal schedule.

- From July 2024-25, a reduction in the 32.5 per cent marginal tax rate to 30 per cent.

There is also additional support for small businesses:

- An increase in the instant asset write-off threshold from $25,000 to $30,000. And an expansion in access to medium-sized businesses (that is, those with aggregated annual turnover of $10 million or more but less than $50 million).

- Fast-tracked tax cuts. Companies with an aggregated annual turnover below $50 million will now face a tax rate of just 25 per cent in 2021-22, five years earlier than previously planned.

- Increases in the unincorporated small business tax discount rate to 16 per cent will also be fast-tracked.

Increased refunds to the luxury car tax for eligible primary producers and tourism operators.

An income tax exemption for qualifying grants made to primary producers, small businesses and non-profit organisations affected by the North Queensland floods.

An increase in the low-income thresholds for the Medicare levy.

Adjustments to superannuation contributions including allowing voluntary contributions to be made by those aged 65 and 66, and allowing receipts of spousal contributions up to and including age 74.

Changes to the ABN system to require ABN holders (1) from July 2021, for those with an income tax return obligation to lodge their return; and (2) from July 2022 to confirm the accuracy of their details on the Australian Business Register annually.

The government will provide $1 billion over four years from 2019-20, including $6.5 million in capital funding, to the ATO to extend the operation of the Tax Avoidance Taskforce.

The planning level of the Migration Program will be lowered from 190,000 to 160,000 places for four years from 2019-20.

Selected spending measures

Key spending measures announced include:

A significant increase in infrastructure spending to reach a total (including existing commitments) of $100 billion over the next decade, targeted at managing population growth, easing congestion and delivering better connectivity for towns and regions. Spending commitments here include:

- A new ‘fast rail plan for Australia’, including a $2 billion contribution to the Melbourne-Geelong fast rail project;

- A $3 billion increase in the Urban Congestion Fund, including $500 million for a new Commuter Car Park Fund

- An additional $1 billion for the next phase of the Roads of Strategic Importance initiative; and

- $15.6 billion for additional road and rail services projects nationwide.

The response to the Hayne Commission will see the government provide $606.7 million over five years from 2018-19 to support action across the report’s recommendations.

There will be $3.5 billion over 15 years from 2018-19 for the government’s Climate Solutions Package.

The government plans to invest $525.3 million over five years to improve the quality of the Vocational Education and Training (VET) system and has pledged $291.6 billion to the end of 2029 for government and non-government schools.

The government will provide $3.1 billion over five years from 2019-20 to support North Queensland in recovering from the 2019 flood.

The provision of $220 million over four years from 2019-20 to the Department of Communications and the Arts to improve regional telecommunications.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content